Academia: Ask For a Ladder

Thursday's Child Has Far to Go

The New York Times wrote about a huge range of adjustments that universities and colleges across the United States are making to their rules and codes of conduct. There’s an interesting contrast between the variety of the technical strategies being employed and the singular purpose of the changes, which is to prevent protests of the kind seen last spring. Or arguably, to prevent protests of any kind from this point forward.

I’m interested in the conceptual underpinnings of these various changes, the reasoning behind them. There’s a theory about what rules produce down there in the foundations, and I think it’s not just a theory held by current administrations or trustees. To get to what lies underneath, you have to survey the rules that academic institutions maintain and the historical layering of how and when those rules ended up in various handbooks and manuals. Such a survey also shows that highly formalized rules sit as solid landmarks within a dense underbrush of guidelines, rules of thumb, and tacit expectations, and that not all rules that are written are necessarily commonly or evenly enforced.

Academic Misconduct

If you divide up those rules into associational clusters, the first grouping that you’d find on almost any American university—and would find in nearly every institution of higher learning worldwide—address academic conduct, primarily integrity in the taking of examinations and the submission of work in courses. These rules usually offer precise definitions of academic dishonesty of various specific kinds: plagiarism, cheating on examinations or quizzes, unapproved collaboration in completing assignments, and the re-use of work completed for one course in another course without the instructor’s knowledge. Many academic misconduct codes also permit instructors some degree of flexibility to argue that a particular student otherwise violated expectations for academic integrity in order to prevent students from finding loopholes that violate the spirit if not the letter of the rules.

Some American institutions use “honor codes” that oblige students to report other students if they witness or hear about academic dishonesty. Most rely on faculty to initiate academic misconduct complaints against individual students, and frequently have stated guidelines or rules that actively require faculty to make such reports. These rules often emanate from different levels of the institution, however—some are departmental, some are divisional, some are institution-wide. Many have internal judicial systems that hear such complaints, but others leave faculty to assign penalties within their own courses (such as failing an assignment) or rely on academic administrators to make expedited decisions about consequences for academic misconduct.

If you participate in any form of social media or professional meeting where faculty congregate to discuss their teaching work, you are very likely to find that a substantial majority of the conversation is devoted to the frequency of academic misconduct among students and strategies for responding to it. Generative AI has become the major preoccupation in those discussions lately, but they are a deep part of faculty life.

The hidden drivers that shape those conversations include relative class sizes, relative selectivity, whether or not a class is hybrid/online or in-person, and the different disciplines involved. Faculty teaching large STEM or pre-professional classes, especially introductory courses, tend to deal with and worry more about academic misconduct. Online classes are considerably more vulnerable to various forms of cheating.

To return to my initial interest, why are these rules a major part of academic institutions, and have been more or less for their entire existence?

Because universities certify to the rest of the world that a graduate who has undertaken a particular course of study has demonstrated the skills and knowledge associated with that degree. Grade transcripts attest not just that the degree was completed satisfactorily but whether the student performed at a high standard.

You might argue that cheating provides its own punishment without any additional sanction in that a student who cheats will eventually arrive at a point where they are unable to demonstrate the competencies and skills that their prior academic performance certifies, at a level that cheating can’t cover. If that’s an upper-level class, they fail the course. If it’s a job, they get fired. But this is a second reason to have rules against it: to prevent that outcome, to keep a student from choosing an expedient path early that will destroy all the value they might have gained from their education later on—a classic “it’s for your own good” logic.

The third reason is closely related to both of these justifications: to protect others who might rely on the competency of a student after their graduate. That applies to any program of study: other scholars and a wider readership suffer in some fashion if a student who is attested to be a trained historian or literary critic is in fact a plagiarist, or someone who fabricates evidence.

Those seem to me to be good justifications and explain the prevalence and persistence of these rules. I think there’s a discussion to be had about the persistence of various kinds of cheating and dishonesty over time among students, and about whether enforcement is the most useful way to prevent it, but I accept that there’s a place for rules of this kind.

Vandalism, Theft and Violence (Including Hazing)

Universities typically have formal rules that shadow but are not limited to common criminal codes against damaging property, stealing property, endangering other people indirectly, or directly harming other people on campus.

The purpose of most of these codes also more or less directly follow the logic of laws that criminalize behavior: to discourage such behavior by threatening punishment for engaging in it, and to provide a mechanism for removing someone who has engaged in criminal behavior from the wider community.

This occasionally leads to a question about why universities have their own codes of this kind rather than just relying on law enforcement. The first answer might be that they want to have the right to remove a student from their institution even when the legal consequences might be only be a fine or some form of probation, that they could have a standard for community safety and the defense of their property that is either more or less stringent than the law provides. They may even want to have the right to remove a student who is not found guilty in a legal proceeding on the grounds that they rely on a “preponderance of evidence” standard rather than a “beyond reasonable doubt” standard.

The second might be that they would also like to define some conduct as unsafe that is otherwise perfectly legal.

The relationship to law enforcement also gets questioned when it runs in the other direction, e.g., where the university’s codes are less stringent or punitive than criminal law and seem to exist to shield the accused from harsher consequences. That conversation comes up most intensely around sexual misconduct and assault, and there are a lot of sides to it that I won’t try to lay out fully here.

The rationale for these codes is first to discourage such behavior and second to provide a mechanism for removing a violator from the institution’s community, either through suspension or expulsion.

I think in general there’s not much to argue about here except inasmuch as you would argue about whether threatened punishment in fact discourages criminal misconduct in the wider world. Universities might argue that the intent here is not to be punitive, just to properly manage risks to safety, but surely most also think that written rules discourage misconduct by spelling out consequences.

There are also arguments about these codes that mimic arguments about criminal justice regarding the setting of thresholds for punishment, for proportionality. Do you expel the drunken student who breaks a window? Do you suspend two men living on the same hall where the two of them have a physical altercation that was only witnessed by others well after it started? What exactly represents real endangerment of others? What’s the difference between smuggling a toaster oven into a dorm despite the danger of fire and crashing into three students at high speed on a motorized scooter? If the strictness of your thresholds communicate that you are in some sense harsher than the law, does that inhibit those activities more?

Other Illegal Activity (Alcohol and Drugs, For Example)

This is famously an area where many universities say one thing clearly in their codes but do not necessarily act with the same clarity or consistency. That’s changed some in the last two decades—one of the side effects of Title IX activism was that many universities were forced to acquire more continuous and specific knowledge about what happened at parties and in on-campus residences and that made it impossible to pretend they didn’t know what they didn’t want to know. But there were many other drivers pushing universities towards having to enforce their codes in this area more stringently.

Even so, students who are canny enough about their illegal consumption generally can do as they wish—campus safety officers are not busting down every door every night. Generation Z seems somewhat less inclined to excess in any event, so that also eases the tension over codes in this arena.

These rules often are a big concern for communities next to universities. There may be a local economy that depends on supplying students, but there are also usually neighbors who want universities to be aggressive enforcers of their rules when the students involved walk through or reside in neighborhoods adjacent to campuses.

Student affairs professionals will sometimes justify these rules under the heading of wellness, as being for the student’s own good. But many of them know not to make this logic the primary reason for having such codes, if for no other reason than a legal adult is allowed to drink, smoke tobacco or (in some states) marijuana as they see fit. If your code is about wellness, do you stop enforcing wellness at 21? So the justification generally is more about legal compliance and secondarily about discouraging substance abuse from leading to other code violations. (Violence or vandalism, most particularly.)

Does it work? Gen Z’s abstemiousness notwithstanding, not particularly. E.g., the existence of codes has not notably deterred students from drinking or using drugs when they are determined to do so, and that determination seems to come from roots that are substantially independent of what a university wants you to do and not do.

“Parietal” Restrictions

As I noted in last week’s column about the gatekeeper era, most of these rules and their underlying logic of “in loco parentis” have been completely removed from campus codes of conduct after more than a century of being one of the defining features of campus life in the United States. Just to use my own college as an example, in the first half of the 20th Century, students had to have the permission of faculty to leave campus at all, were formally forbidden to engage in any form of sexual or romantic contact with other students, had strict curfews, had to conform to a dress code, and so on. (Before 1945, drinking was also often prohibited under this logic.) Some might argue that some newer regulations on some campuses concerning affirmative consent in sexual relationships and so on resemble or recreate parietal rules, but for the most part I don’t really think that’s the case. There is one major ongoing exception here, and that is religious institutions that maintain strict moral codes and often require specific professions of congregational or doctrinal loyalty from students and employees. Did those codes work back in the day, or work now at religious institutions? I think you could safely say “Yes, sort of”, but that’s because they were aligned with strong general social prohibitions at that time or with religious institutions now, because they reflect the voluntary willingness of students to abide by those constraints. Once premarital sex became more common outside of universities in the 1960s, parietal rules stopped being effective inhibitions even if they were still on the books and technically in force.

Protest and Expression

So now let me circle back around to the main point for the existence of this essay. I think the current revision of student codes unfolding across the United States pretends to be concerned with a general vision of regulation, behavior and punishment but is substantially intended to suppress protest or expression on a specific issue, namely, the Israel-Palestine conflict.

The legally necessary pretense that this is a general position, however, is driving many institutional leaders and their enablers to act as if the past failure to enforce codes that could or did apply to protests is a general problem that they are solving through revision of the codes and a commitment to enforce them rigorously. Which in turn is likely to have consequences beyond this specific cycle of protest concerned with the situation in Gaza.

So first off, what are those existing codes and how do they connect to all the others I’ve mentioned?

One set of codes that might have been applied to past protests have some relationship to codes addressing vandalism or property management. Many of those potential applications would have resembled the kind of restrictions that some HOAs impose on property owners to address the upkeep of appearances and maintain property values. In these kinds of codes, students (and other community members) are often enjoined to remain in accepted common areas, to not step in garden beds, to not monopolize resources, to restrict usage of some parts of campus to specific approved activities, to not enter faculty or staff offices without authorization and to leave when told, to not put signs in improper areas, to not hang banners from dorm windows. On most campuses in the past, these kinds of regulations generally have only been used in extreme breaches of the norms they reference, for both protests and in other contexts.

A second set of potentially relevant codes extend outward from rules that address physical safety, physical endangerment, threatening conduct, harassment, and discriminatory behavior. Many episodes of campus activism since the 1980s have demanded the extension of such codes or their more stringent application to the behavior of students (and faculty/staff) not involved in protests, but these rules have rarely been applied to protesters until the last decade. One of the ironies in the present expansion of and enforcement of such rules is precisely that some of the people who regularly criticized previous attempts to expand the definition of harassment, to create hate speech codes, or to extend framings of safety and harm in existing codes are now invoking harassment, hate speech and safety as justifications for enforcing rules and rewriting existing codes to prohibit or punish a wider variety of actions. (Of course, the irony applies in the opposite direction as well in that people who advocated such expansion in the past have suddenly expressed sharp skepticism about “harm” as a framing concept for disciplinary action against students.)

In the recent code revisions, I see a significant attempt to amplify language concerned with “disorderly conduct”. In American legal frameworks generally, that’s a somewhat notorious pretext for police to conduct arrests or respond aggressively. In universities, the use of such provisions for discipline has largely been restricted to the aftermath of breaking up parties that have become too rowdy, noisy, or are over an occupancy limit, or to deal with students under the influence who are making a nuisance of themselves in the public spaces of the campus. Often students who have committed misconduct in those situations are in violation of other rules and the vagueness of “disorderly conduct” isn’t required.

At the same time, what is markedly not covered in these current code revisions is language on freedom of expression or academic freedom. The reason is obvious: institutions that are revising their codes are trying very hard not to claim that they are prohibiting speech or political action based on its content, even if private institution have some legal right to do so if they wish.

So Why Intensified Enforcement and Extension of Codes To Suppress Protests and Activism?

What is the theory here about these revisions—and for that matter, the use of codes of conduct to sanction the actions taken last year when many previous examples were broadly ignored by university administrations?

The first claim might be, “We are using these codes now because there is a unique circumstance now, which is that protesters are harming, threatening or making unsafe a specific protected class of community members.” Here the argument is that there is in fact no change of heart at all within administrations: they are simply doing what they have always been obliged to do by these codes of conduct, and it is the specific tactics or actions of the protesters that is creating the uptick in enforcement.

The problem here so far is first that the particular basis for claiming harm or threat is highly contested. I think there’s little dispute that if an activist were to physically hurt another individual, threaten direct physical harm to another individual, or to persistently harass another individual, there would be absolute continuity between past enforcement and present enforcement. But at least on some campuses, the argument that expressing a belief that the state of Israel in its present form should not exist is equivalent to threatening physical harm to another individual.

In this case, I think there is serious discontinuity with the past. This is not how these codes of conduct have been used in past situations. For example, many activists at the height of the first wave of Black Lives Matter protests on campuses argued that students who responded to BLM protests by saying “All Lives Matter” were threatening or making the environment unsafe in a way that should be actionable under codes of conduct. Almost all university administrations rejected that formal claim even if they also organized various programs and presentations intended to discourage those kinds of verbal ripostes or forced students to join mediation efforts of some kind. Some of that activity drew criticism for its heavy-handedness or its implication that offending students might face disciplinary action in the future, but it was not the sort of conduct enforcement that is going on right now in American universities.

To keep pushing my major question to the forefront, though, let’s suspend the question of whether this is a change in policy and ask whether the theory of disciplinary action (even in pseudo-disciplinary efforts to change thinking or force mediation), is the theory sound? Do codes of conduct prevent or discourage harm or threat in these contexts, and do they do so more effectively if they are enforced?

That’s a big question once you fold in the very long-running argument about hate speech codes and similar legal instruments in society generally. I’m going to say that in universities specifically, the answer is “Maybe? A bit?” But I don’t think disciplinary codes have much to do with it. I think it’s first because the baseline sociocultural norms in universities generally push against using invective against protected classes, especially directly at other individuals, and because the mannered cultural worlds of people with college educations reinforce those inhibitions. The codes in some sense are the expression of values rather than the cause of them: they tell us what the community thinks it is and wants to be.

So believing that because you have rules and because you enforce the rules, people behave with greater expressive civility out of a fear of being punished is only slightly correct in this respect. Faculty, for example, usually try to keep a lid on their invective around other faculty not because they believe they will be punished but because they’ve internalized a particular vision of professionalism or simply because they don’t want to start a reciprocal cycle of conflict with colleagues. Once those two constraints are bypassed, things can and do get nasty, perhaps even with legal or disciplinary consequences. But the fear of the law or of rules is not keeping things in line for the most part. I think this applies generally to students as well: what’s in the code of conduct is not the cause of incivility that some would argue rises to the level of threat or menace.Mostly, university administrations around the country seem willing to admit that they in fact are not acting continuously as they normally have, and are in fact enforcing codes that rarely have been used and are altering codes as well. What is the theory behind this change?

The most immediate thought in evidence is “If we more consistently punish violations of codes of conduct and we rewrite those codes so that they comprehensively forbid almost all of the political activity seen on campuses last year, we will effectively discourage or even completely halt all such activity”. The further implication might be “Not just now, but going forward: we are changing because it was a mistake in the past to be lenient with protests and activism.”

Before I get to the philosophical implications embedded inside of that thinking, I think it’s important to just say that whether constraining protests is a valid goal, the theory of increasing punishment as a way to change behavior in this case is empirically dubious. There’s a reason why past administrations didn’t use their codes expansively or make changes to them, which is that they understood that increased punishment did not in fact work to suppress protests, but instead intensified them and recruited new participants who might not have been sympathetic to the initial causes but did object to harsher disciplinary action. In the case of the 1960s, you might argue that protests ebbed first simply because protesters became more extreme and factionalized to the point of losing support among students (no effort from administrations required) and because some demands were either met or the underlying causes of protest became less important. (Say, the end of the Vietnam War.) Even shooting and killing protesters at Kent State and Jackson State did not cause protests to immediately diminish: quite the opposite.

The goal of campus activism since the 1980s has often been to provoke a response from a college or university, especially in the cases where the ostensible cause is actually far beyond the scope of what those institutions can meaningfully act upon. Since that time, most administrations have understood that point clearly and have therefore declined to take the bait. So if the theory is “Harsher punishment will suppress these protests”, I’m pretty sure that is a defective theory, in particular if activists change tactics to make administrations appear punitive, censorious, or arbitrary, as they likely will.If that is the theory, it does also raise the philosophical question of why administrations have suddenly decided that protest and activism should not be a part of the college experience for both the young people who get involved and the young people who have to form their own opinion about protest based on witnessing it and discussing it close at hand. After all, we are now almost sixty years into that being the case, and mostly protest seems to have been a very healthy part of the learning process even for those who don’t partake of it. Colleges and universities may be clearly acknowledging a change in their approach to protest and thereby in some sense a changed perspective or understanding on protest. However, I think you will look in vain if you are seeking a worked-out philosophical defense of that change, a values-driven argument about why a post-activism, post-protest university is a better one. I think you look in vain because most administrations aren’t prepared to argue that a university that is more subject to discipline and punishment and therefore more orderly is in any sense doing better at fulfilling its core mission. That isn’t consistent with encouraging scholarly research, it’s not consistent with encouraging vigorous argument and analysis, it’s not consistent with most prevailing ideas about how people learn. It may not even be consistent with making people feel safe, since a more punitive and rules-driven environment often produces the opposite structure of feeling.

Which leads me to a final thought. It may be that universities and colleges do not actually believe that changing their codes of conduct or enforcing them more aggressively will suppress or discourage protest on their campuses. They may not actually have a theory about the consequences of punishment in mind at all. Instead, the point of these changes may be to convince people outside the institution that the institutional leadership agrees with them that these specific protesters, with their specific cause, are bad.

I mentioned earlier that codes of conduct in the case of addressing harm, safety, and threat, especially in regards to speech, represent less a mechanism of enforcement and more a statement of underlying ideals, of ethical aspirations. You could even choose to see academic misconduct codes in that way: not a commitment to find and punish all cheating, but a statement of belief that people engaged in scholarship and learning ought not to cheat.

However, sometimes codes of conduct and other official documentation do not reflect the will of entire academic communities, arrived at through some form of general consultation with faculty, staff, students, trustees, alumni and local publics, nor are they long-standing inherited commitments to widely understood norms. They are instead instrumental statements made by smaller groups intended to protect against liability, assert their particular authority, or reassure specific highly valued stakeholders.

You could read the aggressive use of codes of conduct and many of the changes made at various universities and colleges over the summer as only that, as privileged communications being made to privileged and powerful recipients, to donors and governors and mayors and well-connected alumni. An assurance of agreement that these protesters, with this cause, are anathema, whether or not anything can be done about them—but an assurance that cannot be made bluntly or plainly in that fashion for reasons of internal politics and because of legal constraints. Presidents and deans know they cannot quite say “We disdain this cause and its adherents”. But they can say “We’re going to get tough on them using our existing codes, using some revised codes, just you watch.”

If there’s any validity to this thought, I can only say to those leaders: that’s a big mistake. The people they are trying to reassure via a pledge of getting tough will not be assuaged or reassured that administrative leaders are on their side. There is no satisfying them except through the successful suppression of all protests and public activism concerned with the Israel-Palestine situation. Any attempt to actually pursue that goal rather than just talk tough is going to intensify protests and intensify bad feelings between protesters and those who feel harmed or distressed by them. The people who are angry about the protesters regardless of the conduct they exhibit will remain angry no matter how desperate the attempt to mollify them with promises of disciplinary action against protests. The people who are protesting will protest more until they’re all expelled, which will remove a very large group of excellent students from the institution and leave many who remain deeply upset and alienated by that outcome. The students and faculty who are neither protesters nor angry about protesters are likely to be more and more distressed as they see some peers more harshly disciplined, as they see students in their own courses fall by the wayside or feel more and more helpless watching the relentless ratcheting up of the stakes.

And faculty at least will fear the implications of a harsher enforcement regime begin to crowd into subjects well beyond the Israel-Palestine controversy. I’ve argued at times that the creation of South Sudan was a mistake, or that it’s worth considering whether partition and secession could be valid answers to many geopolitical crises. Would I be at risk on the other side of a newly punitive order on campuses of a judgement that questioning the present status of a specific nation makes some people feel unsafe in my presence?

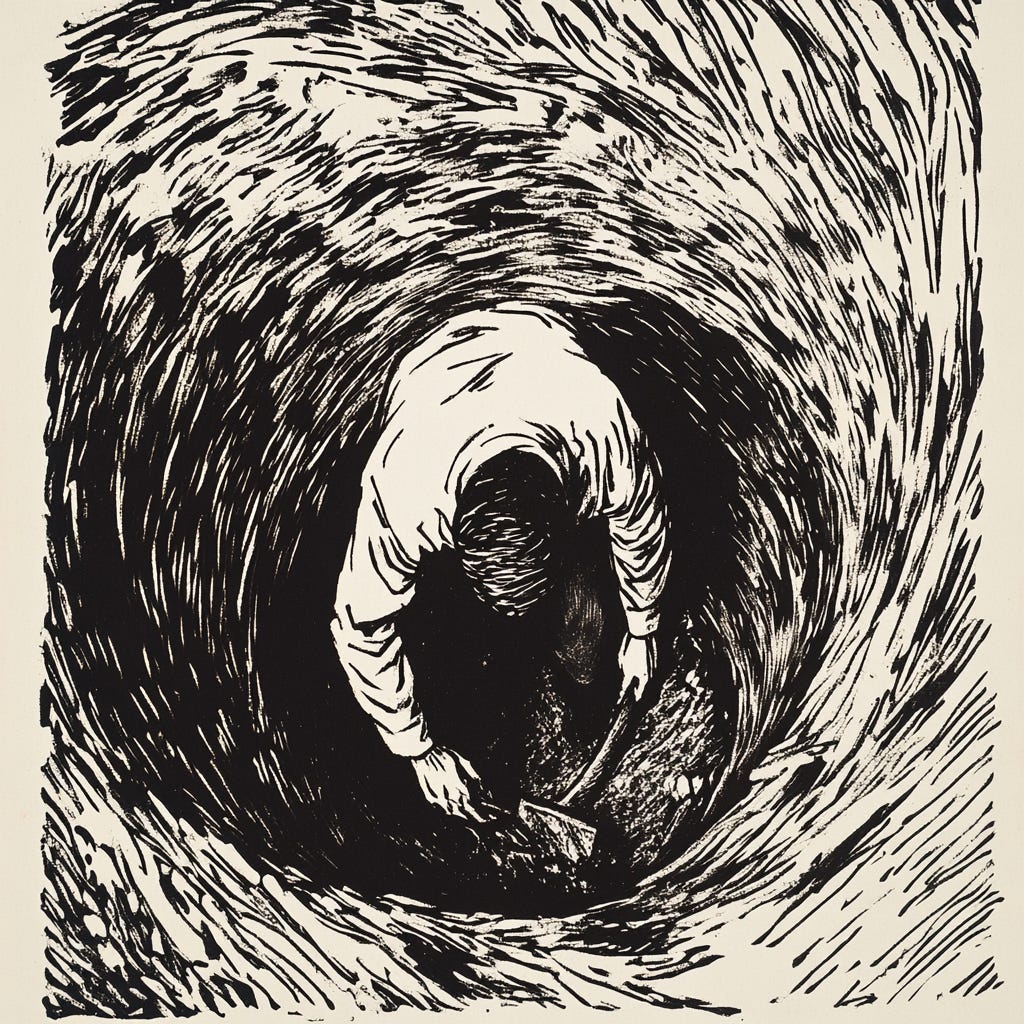

The more code violations there are and the more asssertively they are applied, the more that universities will find themselves legally trapped by the precedents of their recently past actions, even if that ends up profoundly damaging what was previously highly functional and productive about their institutions. Path-dependence is a harsh taskmaster. When you look up from that hole and think of asking someone to throw more shovels down, take a moment and reconsider. Maybe it’s time to ask for a ladder instead.

It's patently obvious that the restrictions are entirely to do with the content of protest, namely opposition to the Israeli state, or at least the Netanyahu government. But if Trump is defeated, the US government will eventually adopt a similar positiion, as most other governments are already doing. I don't know how this will turn out, but administrators are going to look really bad. Implicitiy, university managers are betting on a Trump victory

Tim, well laid out. I would say a lot of your writing in this space engages with how college and university leadership has lost the capacity and will to present the campus as a special space that must protect, even encourage, such debate. They may have lost an Interest in speaking with students who express feelings of being at risk. Maybe they have lost any sense of how to deal with “talking points”. And they surely have lost any sense of how to speak back to donors.