Academia: From Tragedy to Incompetence, One Quadrant At A Time

Friday's Child Would Love to Be Given More Information

I frequently write about the roots of mistrust within contemporary universities, which closely tracks against similar kinds of discontent with management practices and workplace climate in many other institutions (hospitals, law firms, civil service, big companies).

I keep coming back to one central root of that mistrust, which is the dramatic intensification of information asymmetry within big organizations. That shift is especially at odds with the mission of universities, it is a bad fit with their prevailing culture, and it runs entirely counter to the frequent invocation of community, shared governance, and consultative process as supposed watchwords.

Early in my career, even when I was quite junior and not well known to administrative leadership, I found that the amount of information about decisions, trends and problems within the institution that was kept rigorously confidential was relatively small. There was usually a good match between what we were all told through memos and communications and what we all understood to be happening behind the scenes. The “room where it happens” was relatively porous: people who participated in decisions were usually free to describe most of what had been said and thought in the process of making a decision. If you were in the room where it happens, the people with the final say=so usually laid it all on the line.

In talking with colleagues and friends at other institutions who are around my age, I find that they mostly have the same sense of their own colleges and universities. A bit less for large universities simply because of scale, and there are famous cases of secretive or even paranoid-authoritarian management styles that go back a long ways—the Harvard Corporation, say, or John Silber’s tenure at Boston University. It’s important not to indulge nostalgia.

Friends have also pointed out that my own sense of access to flows of informal information-sharing has something to do with being a white straight man, with my cultivation of collegial ties to administrative leaders, with doing a lot of administrative service work, and with my active interest in the history of higher education. Your mileage may vary, but no matter where you’ve been in the past, you almost certainly are feeling as if a lot is being kept from you now.

Thinking about this problem today, I imagined it as a crude quadrant chart. One axis is “Can this information be shared?”, the other axis is “Would people agree with decision-makers if they shared this information?”

So in Quadrant 1, you have information that absolutely cannot be shared, but that people would agree with the decision-makers if they only could share the information.

In Quadrant 2, you have information that absolutely cannot be shared, but where it’s fairly certain that people would strongly disagree with the decision-makers if they did share the information.

In Quadrant 3, you have information that could be shared, but where it’s quite likely that people would passionately disagree with decision-makers if they did share it.

In Quadrant 4, you have information that could be shared, and if it were people would generally agree with the decision-makers about what they chose to do.

My contention would be that over time #2, #3 and #4 have become more populated with both routine and major decisions and decision-making processes. Each quadrant spurs a different kind of reaction from the wider community of people who work and study at a university or college.

I think of Quadrant 1 as the tragedy of leadership. Every decision that falls somewhere in that quadrant is something that decision-makers are dying to tell everybody else about but they just can’t. They know that if they could only show everyone else all the information they have, there would be broad agreement that the leaders did the right thing. If it’s just barely a confidential matter, they may try to find a way to leak the details, but frequently there are really strong legal constraints preventing even that from happening. In this quadrant you find some firings, some tenure denials, some disciplinary actions, some budget cuts, some sudden decisions to spend a lot on a building project, some rushed policy initiatives. When Quadrant #1 was the main reason why there was a lack of information about a visible decision, people (mostly) accepted being told that there was a good reason for the action that had been taken and were appropriately wary of colleagues who tried to get them riled up about it, guessing that those colleagues either had no idea what they were talking about or were trying to cover their own asses for some reason. The first time you’ve been in the room for a highly confidential discussion and then had some colleague rant at you about what happened in that room without that colleague knowing that you were there is a major education about how casual some people are about making things up out of nothing.

Quadrant #2, on the other hand, is what feeds the hermeneutics of suspicion, it is what makes people certain that lawyerly circumspection is a convenient excuse for hiding embarrassing mistakes, conflicts of interest, and conscious distortions of agreed-upon processes. I think of this as the domain of paranoia: both paranoid feelings in a wider community and in the elaboration of deceptions undertaken to hide the information in these cases. The more certain people are that confidentiality and legal compliance are being cited in order to protect decisions that would produce legitimate anger or criticism, the more likely they are to express invented suspicions about decisions that are really Quadrant #1 cases. Quadrant #2 examples sometimes end up exposed to wider scrutiny because of legal action proceeding to discovery, or sometimes because one person involved spills the beans later on (accidentally or intentionally). There are diagnostic signs of a Quadrant #2 decision: assertions of confidentiality that become inexplicably bloated well beyond the specifics of the decision, the sudden exclusion of people from a “room where it happens” who normally would be sitting in it, aggressive action against critics (both those whose suspicions are well-founded and those who are just making wild guesses). The more confirmed cases that fall into the quadrant of paranoia in the historical memory of a university, the more that the tragic dimension of Quadrant #1 intensifies—increasingly no one believes that there are any cases where the information being kept from them where the decision was legitimate.

That being said, even when the details of a concealed decision in the zone of paranoia are revealed, communities often agree that there was some legitimate requirement to keep that type of information confidential. I remember a controversial tenure denial at my undergraduate institution where the slow revelation of the details behind it in the years since made a number of faculty and administrators look very bad, but that didn’t necessarily spur a general sense that the details of all such cases should always be fully transparent.

This is different than decisions that fall into Quadrant #3, which I think of as the domain of fury. The more decisions that fall into this zone, the more untenable the relationship between leaders and their institutions become, the more that a slow burn of alienation and anger can rise and become fully broken relationships, comprehensive rejection, a total negation of business as usual.

In the quadrant of fury, there is no legal reason or normalized confidentiality that prevents information from being substantially shared with all the people who have a stake in a decision. Instead, information is bulwarked or suppressed simply because the decision-makers believe (usually accurately) that the wider community would be very upset not just with the decision but with the actual reasons that it has been made, or the actual mistakes involved in the decision-making. The people doing the deciding have been incompetent, they’ve been maliciously targeting perceived enemies, they’ve been grossly self-interested, they’re favoring a hidden influencer who ought not to be involved in the decision, they’re covering their asses.

In any of those cases, it would be far wiser for the leaders to judiciously acknowledge mistakes and miscalculations, to identify where the fault lies, to bring everybody who cares into the room where the next steps happen. The more that kind of widening out of attention to problems happens, the more that any fury ebbs away. But then the fury never builds in the first place if there are many eyes on all decisions, if there was never any shareable information withheld, if the real reasons for doing something were always on the table.

The zone of fury is what is paralyzing so many universities and colleges right now. It’s not just about making the job of leaders harder or making more faculty, staff and students disconnect from the institution, it is actually impeding all forms of work, all types of value production, all the kinds of life that exist within the campus walls. Fury is in this case a profound friction, a deadly stillness.

My sense is that Quadrant #3 has swallowed more and more decisions in most institutions, that it enshrouds all forms of managerial labor as a kind of reflex, no matter how disastrous the consequences of its spread.

But Quadrant #3 is also the reason why Quadrant #4 is more and more populated. Decisions in Quadrant #4 are trapped in the zone of incompetence: they are decisions that most people, most stakeholders, would agree with and support, where the background information could be shared and yet is withheld.

Why is it withheld? Because of the growth of paranoia and fury. Because information security is being used to hide bad decisions, illicit reasoning, debatable premises, and because the wider community is suspicious and angry as a result, decision-makers figure that all information will intensify suspicion and anger. As a result, they clamp down on information that is exculpatory, that demonstrates their competence and diligence, that shows they are thinking in properly cautious or judicious ways. This is particularly true for people in the middle of leadership hierarchies, who accurately figure that if they release information that makes them or their bosses look bad, they will suffer serious professional consequences but that if they release information that makes their office and their work look good, they will receive none of the credit themselves. It’s all risk and no reward.

Except the reward would secure the general functioning of the institution, would be a rising tide that floats all the boats. Much of the information trapped in the zone of incompetence is the information that used to flow freely both formally and informally, that created trust, security and resilience within institutions. The problem is that it can’t be freed to flow again without also reducing all the information trapped in the zone of fury, which shouldn’t be withheld either. Everything on that side of the chart is information that stakeholders have a right to know, that is essential to consultative process, that makes an institution align with its values and accomplish its goals.

What higher education really needs now is leadership that focuses on making sure that all of its withholding is purely tragic, that what is kept back is what cannot be shared but that hides nothing about leadership itself except the fact of their competence, skill and judiciousness. We all want to believe that the only things we don’t know belong in that quadrant, that the burden of leadership rests primarily in being the custodian of truths that cannot be shared.

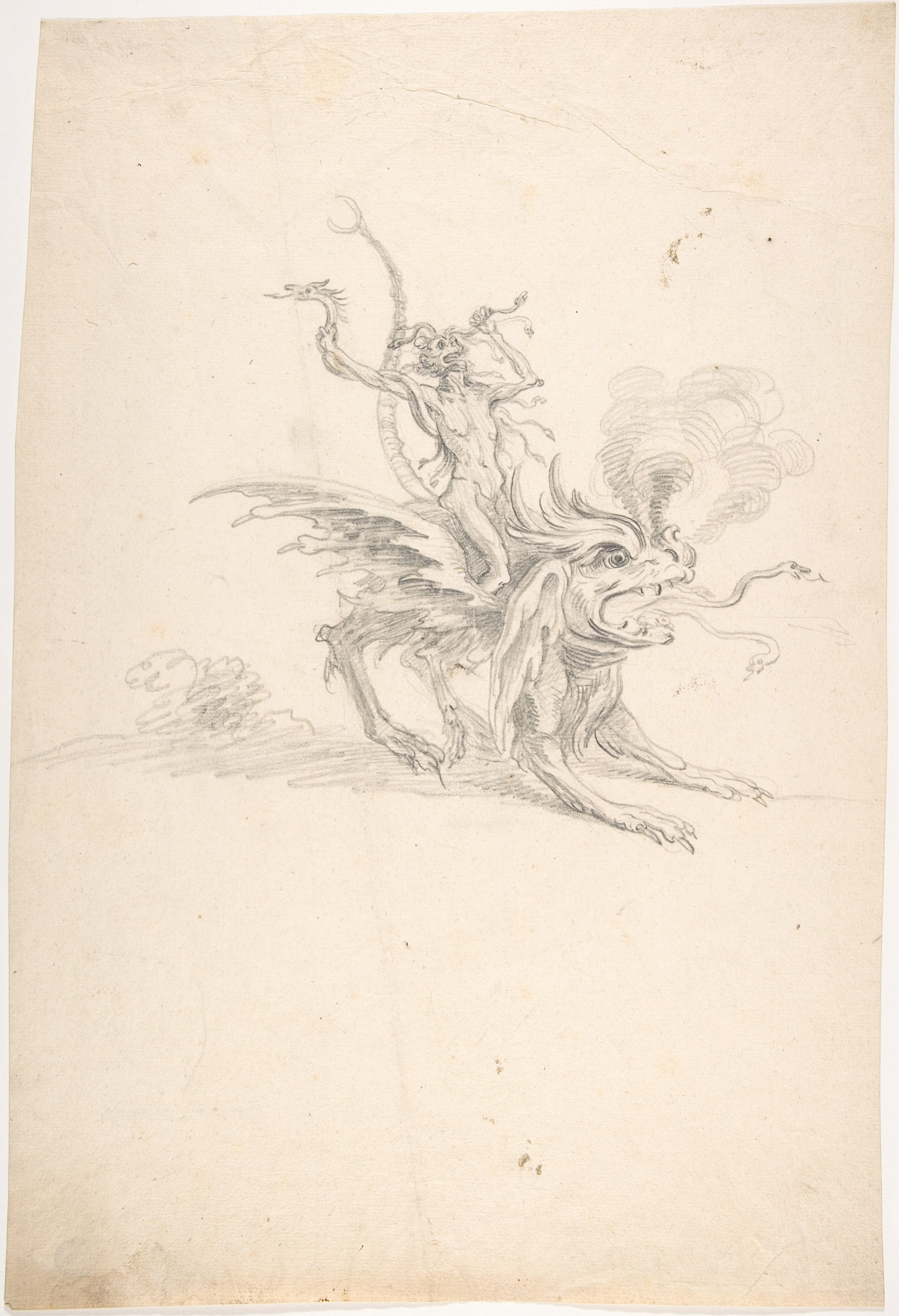

Image credit: “A Fury Riding On a Monster”, anonymous, 18th Century Dutch drawing.

I think there's a specific version of the quadrant of fury that's very relevant today. That's when information is restricted because the administration thinks that everyone else would be mad, but also thinks that everyone else would be wrong to be mad. For example, because they want to appease conservative politicians to avoid worse outcomes or close programs that they think are unsustainable. Sometimes this is driven by different assessments of the world, sometimes by different values, sometimes by different orientations towards resisting bad trends. But in all situations this is extremely toxic to the relationship between the administration and everyone else.

One result of all this is that, when information does leak out, the implications are often catastrophic. Think of the leaked DNC emails in 2015- the content wasn't new (the party backs candidates it perceives as winners) but hte fact of leakage was