In the room where people unite and schism, talking of whether it’s all just fascism, there is a point that I think doesn’t get highlighted enough.

I am very much in the “if it looks like a duck, and quacks like a duck, it’s fascism” camp. However, it’s worth remembering that the European states that pioneered fascism in the modern era were all of them in their way fragile sovereignties. Germany and Italy were new nations when they went into World War I, and Italy in particular was still reeling from the conflicts that went into making the nation. Portugal and Spain were older sovereignties, but both came out of the 19th Century reeling after complex reconfigurations of their political systems, their vision of political legitimacy, and with a sense of sudden marginality in global affairs.

Fascism original-style was partly about the fears of old peoples in newly created or configured countries who had not had much time to grow used to one another, and the desperate desire of their new countrymen to avenge their humiliations in war, in economic power, in international influence, to use their new nations to revitalize what they imagined to be old prerogatives of their peoples.

Fascism in America, as predicted, has arrived carrying the cross as well as draped in a flag, but some of it seems to be a matter of the fears of newer people about the newest people in an old nation, tearing at the fabric of a long-standing sovereignty. Postwar America humiliates itself internationally in imperial misadventures with depressing ease, but Trumpism doesn’t feel as if it is primarily concerned with Iraq or Afghanistan as such, except to needle the Biden Administration (basically for doing what Trump was winding himself up to do but didn’t have the courage to close the deal on).

Trump, after all, is only a third-generation American, and his wife a first-generation one. That’s quite the pedigree to be sounding off about America as a garbage can, to repudiate the New Colossus. It is par for the course in American history, however: it is not the true natives nor the oldest settlers who go coocoo for nativism in its periodic eruptions, but the most recently settled, who fear being turfed out of whatever place they’ve secured for themselves.

Maybe it falls to others to remind the old nation of how far it’s come as well as how far it has to go. Most especially those who have born the brunt of its failures and those who have done the hard work of trying to make it better.

Maybe even those of us who can boast neither of unceasing devotion to the work of change nor of any suffering along the way. I am the descendant of old arrivals: early 19th Century English and Irish migrants, and earlier still another group of English settlers named Higginbotham, who traded in and owned slaves imported from West and Central Africa.

I didn’t know that last until quite recently, when I pressed back a bit further on the branch of my own ancestry that I knew the least about, past the point where my Higginbotham ancestors in a more recent generation left behind the larger bulk of their relatives in West Virginia to come to California.

I can see on the map of West Virginia’s 2020 vote that I am separated by more than distance from my distant cousins who remain there, whom I have never met or known by name. I can see it’s likely that we are on opposite sides of the fearsome divide now besetting us all.

I would have one truth for them if we ever met, a truth that lives far above the brutal wrestling of 21st Century American electoral politics. The truth is this: we are better now than we were. We old peoples in an old nation, we younger peoples, we newest peoples. Perhaps even at last, the oldest peoples, the first peoples, who have been so brutally treated, are glimpsing new possibilities.

I don’t believe in progress as inevitable. I don’t believe in progress as steady. I don’t believe that progress is more machines. I’m not even sure I think it is in more knowledge. I know, in my bones, that progress is reversible, and I fear that so very much. But we have become better.

Better slowly, better in fits and starts, in three steps forward and two steps back. Never as fast as we should have, never as far as we could go. Never with magnanimity, never with love for all. Never with consistency, never without hypocrisy.

Better for all that. We have become a democracy after having so long been only a fraction of one. We have become freer to think and say what we want. We got closer to taking the meaning of our laws and Constitution seriously for all. We have opened our hearts more to people loving as they will, as they wish.

It’s easy to stop believing in progress, especially in times where fascists in an old nation promise to snuff it out entirely, where billionaires are trying to grab every last penny out of our pockets. We know that people who tell us that everything’s getting better are sometimes trying to stop or slow progress altogether. We know that someone being too satisfied with our accomplishments is like a tell in poker—it is a person who is really saying “We’re all done now, no more work left, so shut up already”.

At this moment of peril, it is worth saying that American greatness is yet in the promise of our later days, in the future we often stumble towards. It can be a bitter feeling to know we’re not there yet, when it shimmers at us so invitingly, so obviously, so easy to envision. That bitterness should not incline us to loosen our grasp on what we have already done. It’s been a long march from the Higginbotham who was the master of suffering and injustice in Barbados and sent his children forth into the land of Virginia, but there’s been ground covered, things that have changed. Not necessarily because of those children who took the land of Virginia from the people living there already. Often in spite of them, but together, some people living and working within these changing borders have gotten things done.

We have to hold strong to that knowledge right now, in the face of a disastrous undoing. These old bones are strong enough to bear generations yet of renewal and change, to further fulfill the deep promises that have so long groaned under so many kinds of chains. We can be better. We have bettered ourselves already. Let’s not let this new fascism take down an old country before it even has a chance to really live.

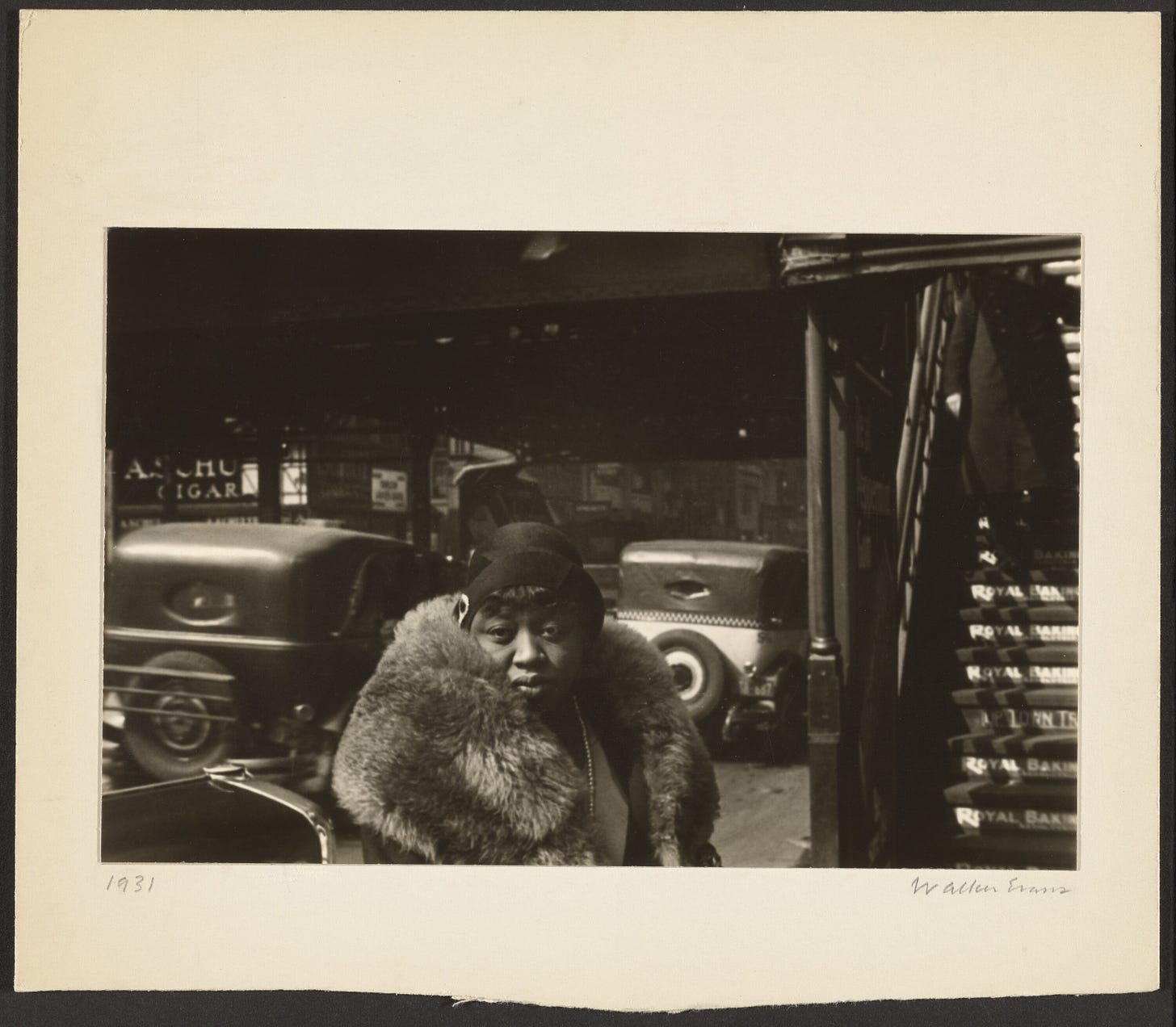

Image credit: Walker Evans (American, 1903 - 1975), photographer 6th Avenue, 1929 Gelatin silver printImage: 12.1 × 18.6 cm (4 3/4 × 7 5/16 in.), Mount: 18.7 × 21.7 cm (7 3/8 × 8 9/16 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XM.956.506.

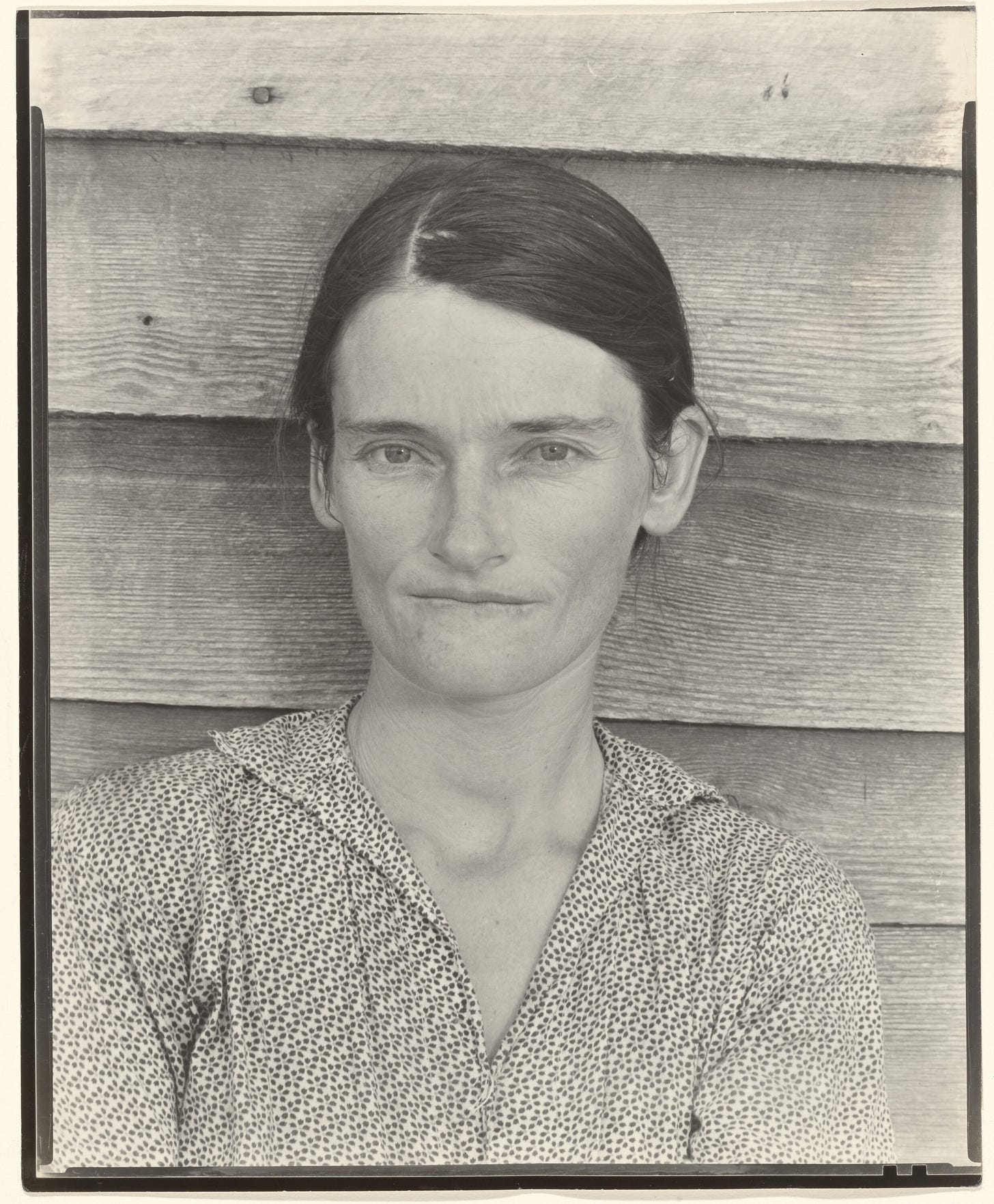

Image credit: Walker Evans (American, 1903 - 1975), photographer Allie Mae Burroughs, Wife of a Cotton Sharecropper, Hale County, Alabama, 1936; printed later Gelatin silver print Image: 24.2 × 19.2 cm (9 1/2 × 7 9/16 in.), Sheet: 24.8 × 20.2 cm (9 3/4 × 8 in.)The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XM.956.517

With you, Tim. Arm in Arm. Thanks for your words.