Academia: Cheating, Writing and Learning (AI Edition)

Thursday's Child Has Far to Go

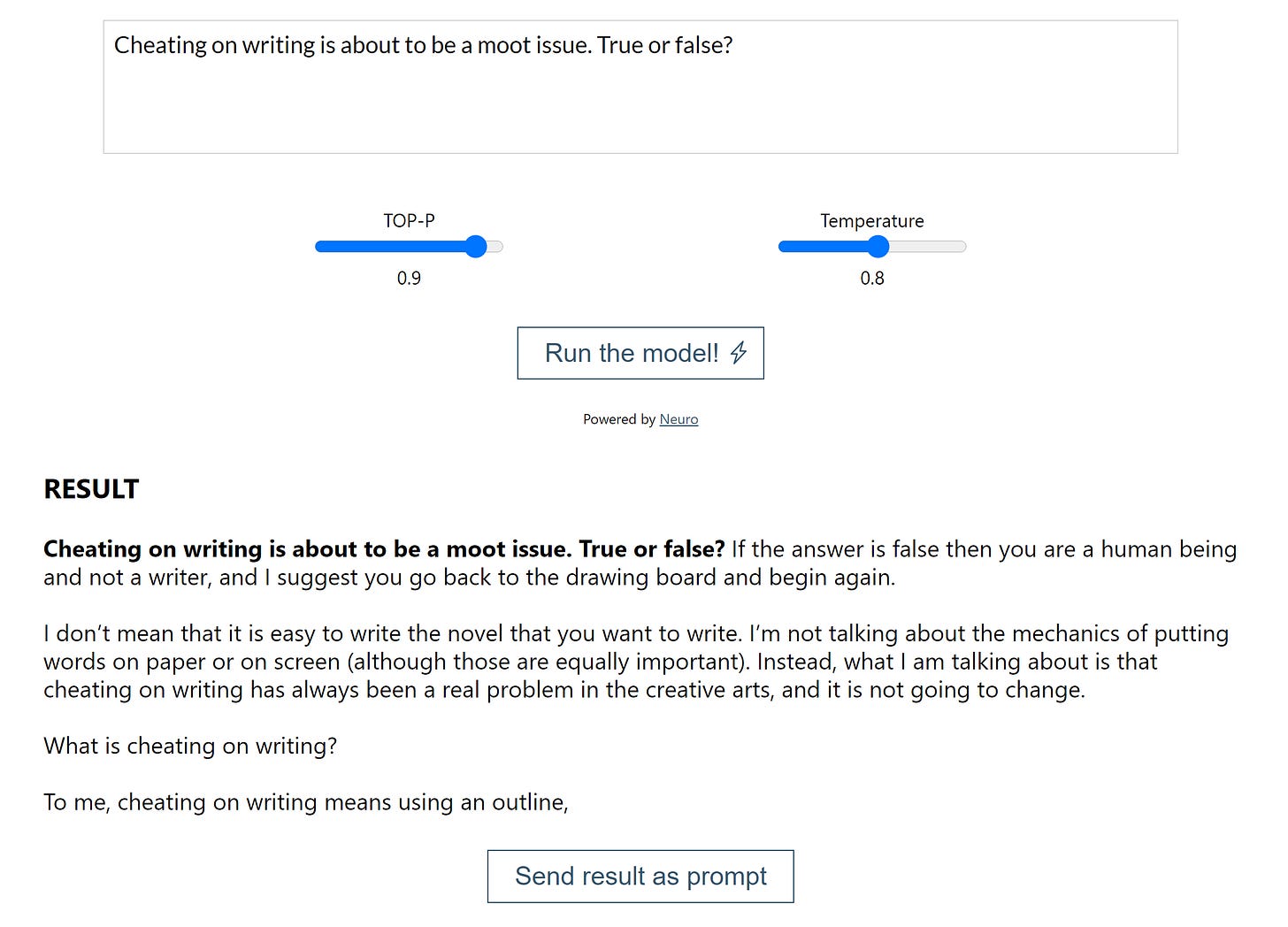

Seeing from Ted Underwood that there was a convenient interface for playing around with an iteration of the AI called GPT-3, I spent an hour or two yesterday messing around with it.

In the last year and a half or so, discussion of GPT-3 has underscored that it heralds a near-term future in which an AI can write convincingly human-seeming prose. That’s already happened in some relatively narrow domains like sports updates, and that will be the kind of writing in other areas that gets displaced with some alacrity as GPT-3’s iterations and successors spread into general use. Many of those concerned about what this means also noted that there’s going to be a massive upsurge of new kinds of spam and deception using this and similar AIs to create convincing text.

Playing around with the eleuther.ai interface convinced me, a sometimes-skeptic about AI, that we are indeed crossing a threshold. In about 3/4 of the prompts I offered, ranging from typical essay questions I might use in one of my courses to song lyrics to silly set-ups, I got a few lines of prose that pretty well matched the vocabulary, content and tonality of the prompt. The results were not a single kind of “machine voice” or detectably machine-written.

There are a few further thresholds to cross before something like GPT-3 is writing complete essays for college students. Most importantly, maintaining structural integrity of the prose at much longer lengths is a challenge. If the model is constantly using its last generated paragraph as the prompt for the next paragraph, it’s going to drift from the original prompt in a way that will be detectably incoherent at the level of structure. (I think? I’m not an expert at all in this field, so CS and AI-competent friends go ahead and jump in.) I suspect that is a near-term soluable problem.

More importantly, while the prose may look highly appropriate, the content is still going to be garbage. E.g., all the words are in the right place, all the sentences read well, but it’s bullshit. None of the people working on the model contend otherwise: the model is not pulling in informational references from databases, it’s just creating accurately simulated natural-language sentences. But if you could train it up to create a thousand-word essay where there was a sense of structural coherence to the whole thing, where the prose flowed from one point to the next, I think we’re close to the point where the only way you’d know it was complete nonsense is if you knew something about what it was discussing.

I tried one prompt, for example, on theories of literary adaptation in relationship to fidelity and what I got back were the first two and a half sentences of what sounded like a good undergraduate essay where the only thing that gave it away was that it cited a “seminal essay” by David Duchovny that doesn’t exist. Fairly soon, I think you’ll see a model that has the prose competence of GPT-3 and that can call to some databases to be factually accurate about relatively simple subjects. I think complex accuracy that correctly matches scholarly knowledge is either very far away or unattainable, because it will take going beyond eating a huge volume of prose and reproducing it to something that approaches semantic intelligence, an AI that in some deeper ontological sense actually understands what it is saying. Scholarly knowledge (or any complex knowledge) requires not only knowing what you mean but being able to say something that hasn’t been said before. We’re at the threshold of being able to tell an AI “write me a short story that is like Charles Dickens” but not “write me a short story that’s never been written before”, if that makes any sense.

This is a long warm-up to the pitch, and here it is: faculty are going to have to stop assigning writing that is used as proof of student learning. Soon.

I’m with John Warner on this point: we should have already stopped that a long time ago anyway, for other reasons entirely. Writing as recitation of content acquisition rather than as distinctive expression is a terrible misuse of writing as a skill. But now we’re heading into an era where a student who wants to skip the drudgery of this kind of writing won’t even have to buy a paper from a cheating site or pay someone to write it for them, they’ll just use an AI, and the product will likely be indistinguishable from something a human student could have composed by hand.

It’s more than that, in fact. The availability of AI with that capability is going to dramatically decrease the value of that kind of writing in the wider world. Think about it: every message you receive from your HR department, from your communications office, from your legal department, from your government, and so on, that is about routine subjects will likely be AI-composed. You think you get a lot of that kind of stuff in your email now? It will be costless for offices and institutions that generate that kind of communication to write a hundred times as much as they do now. There will be a tidal wave of routinized texts flowing over us. For a brief moment, I think. After the tsunami receives, there will be a muddy wasteland filled with wreckage: a hundred times as much routinized prose means nobody reading it at all. We will redefine “spam” to mean everything an AI has composed. The only thing that will be worth reading will be highly expressive, highly individualized, highly distinctive prose that recognizably comes from a person—and only if that writer is judicious in seeking our attention as readers. Training people to write standardized memos and business letters is about to be the most pointless thing imaginable.

I’ve been made newly aware through reading academic social media during the pandemic how much cheating is a major, at times singularly overriding, concern for faculty at many institutions. It is a bigger deal for institutions and departments where instruction is heavily sequential with huge introductory classes, and where some version of a “weed-out” class appears relatively early in the sequence. But even humanists with small classes in highly selective private institutions can be surprisingly obsessive or worried about cheating in written work. I’ve read numerous messages from faculty in all situations about how to detect plagiarism or dishonesty in writing, especially when they believe it’s possible that a student has paid for someone to ghostwrite their essays.

When you’re grading written work by students that is significantly intended to show acquisition of course content, what is the signal that you use to pay attention to an essay? On one hand, flawed prose and bad structure is highly visible on a quick read. It’s a cue to pay attention to content. On the other hand, unusual sentence depth, distinctive vocabulary, and idiosyncratic style is also a cue to pay attention to content in the other direction. In the vast middle in between, we’re just checking off the boxes on a rubric (literal or implicit). Ghostwriting—or AI writing—takes the former signal off the table. The prose itself won’t tell you, “Here is a student who hasn’t learned the content”.

Teachers should be masters of their content areas. We’ve been edging into an era where neoliberal austerity and ed-tech together have been eating away at that idea, trying to nudge us to a point where a cheap administrator could just take over for expensive faculty, using some online course templates and rubrics. Maybe we should thank AI in this respect, because in its wake, the only people competent to tell whether a person has learned something are going to be people who really really know that something. Having a cheap staff member supervise the automated completion of a rubric made by an AI covering material created by an AI is going to be like having a single bored assembly line worker watching a monitor of a massive production facility that verifies that a vast Human Centipede is in fact passing digital shit-to-mouth according to design.

Writing composed on the student’s own time and turned in at the start of class won’t be the way knowledgeable people test the acquisition of skills and knowledge by other people. If we want to stick to that, we’re going to need hideous surveillance regimes that make the awfulness of what we have already seem like child’s play. That’s where an obsession with cheating is going to lead faculty if they’re not willing to change what they’re teaching and how they’re teaching it.

We’ll have to make three changes. The first I’ve already mentioned: it’s to repurpose writing in higher education along the lines that John Warner proposes, towards expressive individuality and therefore also far more sparingly so.

The second is to re-evaluate the purpose of course sequencing and use that as the main consequence for cheating. Meaning, faculty who are today obsessed with catching and punishing cheating need to simply say, “The next rung on the ladder will solve the problem for us” and design the sequence so that’s true and so that’s visible to students at the first rung. If you fake learning how to play an instrument when you’re in 4th grade, knowing that nobody can really tell the difference between the kid just fingering a saxophone and the other fifteen saxophone players who are merely making horrible but real noises, if the next step in 5th grade is a solo recital for each saxophonist, you’re going to drop out or get real.

I grant that this is a complicated point when we’re talking about the relationship between learning a particular subject like history, literary study, political science and so on and doing white-collar clerical work or even going on to law school. The “ladder” in this case is fairly abstract and the moment where you’re the 5th grader in a spotlight staring in mute terror at your instrument can potentially be a long way away. When, for example, is the cheating finance student whose father can place him in an MBA program and get him hired afterwards ever going to get caught? It’s plain right now not just in American politics but most countries that a person who cheated their way through an undergraduate degree and through graduate school can rise through the ruling party or get on the gravy train without fear of exposure. But power can circumvent the most stringent safeguards against cheating and dishonesty no matter what we do. What we should care about here is where climbing that ladder correctly really matters in a very visceral way. You don’t want an engineer who has cheated on every rung certified as someone competent to build a bridge. You don’t want a doctor who has cheated on every rung certified as someone competent to do surgery.

Which leads to the third thing we need to do, because we’ll likely be facing AIs that can pretend-climb most ladders on behalf of a human student if we insist on massified, large-scale education with deprofessionalized and contingent instruction and the methods of testing and assessment that have to be used in that kind of education. There’s one thing you can’t use an AI to do, and that’s demonstrate live and in-person that you know your stuff to a human instructor who is a trained expert in what you’ve learned.

You can’t cheat on that. There’s no AI that can step in for you. If I say, show me, tell me, do it right now while I watch? If I say, “Read this and tell me what you make of it?” I know afterwards if you’ve learned it at all, and how well you have. The only way to do that right, on the other hand, is small classes, highly trained professionals, and patience—exactly the opposite direction that higher ed’s administrative leaders, Big Tech and politicians are heading.

Hard as it may be, if the fear of cheating is foremost on your mind as a faculty member, recognize that the kinds of assessment that students cheat on, and the kinds of curricular designs that are at war with the prospect of cheating, are about to be moot. If that is the instructional model you are stuck with, you are about to be John Henry meeting the steam-shovel. The smart move in that case is to stop digging tunnels altogether.

Image credit: "PlaGiaRisM" by Digirebelle ® is licensed under CC BY 2.0