I’m coming in late with my response to Emma Camp’s essay published by the New York Times.

Earlier this week, Claire Potter made the essential points that I think everyone (including Emma Camp) should grasp: that Camp’s essay (and the other complaints that it echoes) is stuck in a false presentism, in the proposition that just now for the first time on college campuses some healthy culture of heterogenous debate is being interrupted by conformist shaming. Instead, as Potter notes, “for over 70 years, the idea that colleges and universities breed conformism, the natural ally of and the endgame of self-censorship, has been regurgitated and recycled”. Potter rightly observes that Camp is writing in an established genre that calls to college students to throw off conformism, a genre that she sees in emergent form in the twin calls to action of the Port Huron Statement in 1962 and William F. Buckley’s Young Americans for Freedom’s 1960 Sharon Statement.

Potter asks, “why is the American media so addicted to stories about beleaguered young people whose free speech—and thus, a real education—is stolen by elusive, autocratic others?”. At least one answer might be “because at times it has been stolen”, but not in a particularly elusive way. I’ve observed this before in response to similar complaints, but that people who worry a great deal about deplatforming and cancel culture today tend to lack any kind of historical perspective on it: well into the 1970s, there were many colleges and universities in the United States that refused to allow civil rights advocates to speak on campus, refused to allow leftists to speak on campus, and openly imposed various kinds of constraints on the range of acceptable political opinion among their faculty and students. The call to stop being “excellent sheep” and embrace free thought is an old genre, but so also are institutional forces constraining and disciplining what can be said and thought within the walls of academe. You do not find a more and more open and free and debate-friendly university as you go further and further back. This is not a world we have lost.

So my own challenge to Emma Camp and anyone who finds her concerns resonant would be to understand that they are not envisioning a culture which once existed and is now being lost. When I hear senior faculty or old intellectuals bemoaning what they see as a loss of vigorous debate, I also tend to hear what they do not say and perhaps do not know, which is all the things that were not said in those debates they are misremembering, all the opinions and perspectives and arguments that never got spoken in their presence because the people who might say them were not in the room, were not present on campus, or rightly feared the consequences of speaking their minds. If we are imagining some way of talking with one another that is wide open to some vast range of possible views and perspectives, we are imagining a future that we have yet to live within. And if so, it is incumbent on anyone desiring that future to explain why it’s what they want and what it might be like to live that way, within the university or outside of it.

Consider this thought, for example: are there times and places where few if any of us desire vigorous open debate that includes all possible positions or views about what gathers us together in that moment? When I show up at a funeral for a professional acquaintance who is being buried, should I stand to declare my belief that aquamation is the only environmentally sound way to dispose of corpses? Or offer to argue with anyone who believes that a funeral should be quiet, somber and sad by saying that funeral should be a happy celebration of a life well lived? Should I stand on a soap box and declaim my views about the afterlife?

Shall I spend my Sundays walking into churches loudly debating the minister or priest as he holds forth in a sermon? Attend a support group for people dealing with trauma to critique the entire concept of trauma? Show up at a bake sale to denounce sugar because of its polluting history of association with enslavement?

So point #1 about the future that Camp is calling for, though she doesn’t understand it as such: even the people that want to live in that future in the terms she offers would want, I think, for a great many everyday situations to not be defined by or inviting to “vigorous debate”. Here at least we do have a history (as well as future possibilities) to consider: “vigorous debate” is something that we attach to a very specific domain of civil society and pointedly exclude from the rest of it. And the university has not historically been the centerpiece of that specific domain, that “public sphere”, because the university has other purposes as well. In its modern as well as medieval forms, the university in Western societies was associated more with theological indoctrination and the shaping of the comportment of a ruling elite than it was with encouraging free and open debate on the issues of the day. The “public sphere” as we commonly understand it was located elsewhere in early modern Europe into the 19th Century; it extended into the university but was not necessarily of it. Even now, the university has other purposes (as the Port Huron and Sharon manifestos acknowledge) still encoded into its structures besides being sprawling soap boxes.

Which leads to point #2 about this future, should we want to inhabit it, is even when we identify what spaces and situations where some degree of disagreement is not just appropriate but desirable and we agree that the university is generally one of those, even in the most argument-friendly university imaginable there would have to be limits. Is the introductory biology class the right place to stand and demand a debate on the scientific method or a scientific understanding of what constitutes life? Is a mid-level econometrics class the right place to engage in a theoretical critique of the entire discipline of economics? Is a philosophy class the right place to demand the right to dismiss philosophy as a ridiculous waste of time? Somehow the people who want vigorous debate that they’re not getting never really get around to thinking about what the limits will be even if they get what they think they want (and have never had in those terms before). Camp wants a bigger poster on her dorm room door, but would she support a policy that specifies that a student can’t paint their door with opinions (or even just for their expressive, aesthetic preference)? I’d guess so, and you can readily see the basis for a difference in terms of property rights. (The university owns the door, and doesn’t want to deal with the costs of constant repaintings; the large sign imposes no burden on the door owner, in contrast.) But the imaginary debate-rich University of Tomorrow will still have endless numbers of discretionary decisions like that about what debates trespass on the purposes and rights of others. Can I follow someone around with a sign that says “The person I am following is a leftist fool?” Why not? It’s my sign, it’s a valid opinion, I’m willing to debate the leftist fool anytime they want about their foolery. Can I start every single discussion in my anthropology course by insisting that anthropology’s origins are so thoroughly colonial that all discussions convened under its banner are poisoned and no other thing is worth discussing? It’s a valid opinion—people have argued it—so why not?

Which leads to point #3 that this genre of attack on conformism never really addresses, all the way back to its earliest instantiations, which is after we’re no longer conformist within the university, how shall we live together in our new disagreement-defined institutions? Because all writers in this genre, from SDS to Emma Camp, set themselves against what they take to be intolerable and intolerant constraints, and thus cannot project themselves into the collective action problems of the university that might emerge on the other side of those constraints. Does the person followed around by the sign-carrier have a right to opt out of that debate and to prevent the sign-carrier from following them? Even if you are a person who loves a vigorous debate at any time and anywhere, you know full well that debates can be convened on false premises that leave one participant or side locked into the perspective of the person who started the argument. Do the students in the anthropology class who want to learn anthropology have the right to ask that the person who is there to argue for the class and the discipline to cease to exist to leave or be quiet? I’ve never met a person who wants open and free debate to flourish within universities who rejects all constraints of any possible kind. So maybe a major evolution in this genre of writing would be to leapfrog the attack on conformity and move on to talking about how to solve collective action problems in the newly debate-enriched University of the Future. Because what has tended to happen in each successive turn of the wheel is that those who railed against what they imagined to be constraints end up articulating constraints once space is made for their views—both because they were arguing from an ultimately parochial position that defined their views (and their views only) as the non-conforming absence from existing culture and because they know full well that some constraints arise from universities having other purposes than just being soap boxes.

Which gets to point #4. When Camp says, “We need a campus culture that prioritizes ideological diversity and strong policies that protect expression in the classroom” (a staple feature of this genre), there’s little room inside the genre to reflect on how peculiar a maneuver this really is. The call here is to the university as an institution to make culture where it is known in advance what that resulting culture must look like. This is not a call for “negative liberties” (e.g., to a government or an institution to not interfere with speech) it is a call for “positive liberties” (to a government or institution to use its power to produce a particular configuration or form of civil society). I actually find this rather appealing but I never feel on reading any of the works in this genre, right back to the 1960s, that any of the authors really mean it. The writer in this genre generally assumes that there are many people who think as they do who will only manifest as allies with similar sentiments if they are not only freed from fear of consequences but are actively encouraged to speak their true thoughts. The writer in this genre rarely asks, “But what if in fact almost nobody thinks as I do?” This is not a genre that encourages reflection and self-doubt. One does not look to Yascha Mounk to wonder in print or in social media, “Perhaps I am wrong. Why do I think I am right?” where there is some genuine contingent possibility that the outcome of those questions will be “I am in fact wrong”. But there are genres where that is possible, some of which are wholly appropriate to the university or to a larger public culture. The future university culture which prioritizes genuinely diverse thought might be more like Montaigne than Mounk, full of introspection, self-doubt, and an endless exploration of branching possibilities. (Or maybe that’s what we already have, if you look for it.) How narrow and circumscribed it is to envision intellectual diversity as “conservatism and progressivism”, or even “on every issue, vigorous debate”. In a garden where a thousand flowers are truly blooming, there would be rows of beautiful blooms that see all right-left disagreements as dull conformism. There would be laden trellises that see debates articulated through writing or speech as a ridiculous distraction from really understanding the world through embodied experiences, emotionally rich dialogues, entirely interior meditations. There would be people whose sense of truth—scientific, religious, political—genuinely boxes out all possible disagreement. If you are demanding the Future University of Genuine Intellectual Diversity, that all ought to be there when the university is done making the culture that you insisted it use its authority to create. If the university is in charge of creating the outcome, it has to populate every possible niche of heresy and orthodoxy, every possible way of thinking and speaking and discovering and inhabiting truth. Perhaps even every possible way of being false.

If on the other hand all that the writers in this genre are asking is a university that is more interventionist in its defense of “negative liberties”, e.g., that it is more certain that everyone already there is able to speak and think as they wish, then we arrive at point #5: how exactly do we want authority and power to intervene into culture and what would be the diagnostic signs of its success in doing so, if not the production of absolutely maximum intellectual diversity? Because this genre of writing from the 1960s to the present moment is always certain that far more people would think as the writer thinks, speak as the writer speaks, but for a culture that is unnaturally suppressing the writer’s affines. The oddity, as almost everyone critiquing Camp’s essay has noted, is that the writer is usually themselves speaking vigorously in every platform imaginable, without being actively prevented by power or authority and without suffering anything but “piling on”, e.g. the sense of being disagreed with simultaneously by a great many people, with all the emotional and social fear that naturally produces. What exactly is being called for here? What is authority to do to prevent “piling on”? More importantly, why are writers in this genre always certain that if only conformism were not being mysteriously enforced, they would no longer be alone? This genre of writing is always marked by a kind of incuriousness, a sense that the writer’s own anecdotal experience is sufficient proof that they are surrounded by affines who would spring to expressive life if they only were assured that they would not face “piling on”. No one writing from this perspective really sets out to ethnographically investigate, in a completely open and curious way, what it is that people might really be thinking that they’re not willing to say. Not the least because investigating with that premise already in mind presumes a certain outcome, as well as enshrines unarticulated assumptions about what we think. You can’t set off to find out what people really think while also being openly desirous of debate, of a culture that prizes adversarial positions and disputatious conversations. Maybe many people don’t think much of anything about particular topics other than what will make them comfortable in the presence of others with strong opinions. Maybe some thoughts only form as convictions (spoken or unspoken) in an entirely social context. Maybe many people really don’t want to debate or doubt, they just want to find some stable, shared social positioning that lets them get on with what really matters in life. You won’t ever be able to discover the truth of it when you set off as Camp has because she’s already sure what should be the case. And if universities are supposed to be about debate, they’re also supposed to be about seeking truth through research that is open to the myriad possibilities of what might be true.

And maybe, just maybe, this genre is even older than Potter’s on-point cultural history might suggest in terms of the wider public sphere of modern global print culture. Maybe we have been for two or more centuries in the company of people who write against what they take to be the fearful conformity of other people in a quest to find—or produce—more minds like their own, and in finding that their own writing or speech is insufficient to the task, demand that some form of civil or political authority liberate, even actively create, the fellowship that they seek.

Against that I can only say that there is yet another genre that I prefer, which is the writing and speech of a person of conscience who speaks with little interest in changing the structure of public culture, who writes and speaks with the confidence of their convictions and tends to that alone, leaving all other chips to fall where they may. If they persuade other minds or find fellows they never knew they had, so much the better. If they do not, they continue to speak out, think, argue.

And another genre beyond that too that I think is even more suited to the university as it has been and might yet be: the person who is exploring all the thoughts that could be thought, who is as engaged in doubting and questioning themselves as in confronting others, and is gently delighted by or interested in other people exactly as they find them now rather than being certain that they would be some other way if only, if only. Brave spirits may just be best off walking alone with their candles lit and letting others find their way to them if they will or might. Begging authority or power to insistently make people be other than they are, to change the culture to how one imagines it naturally ought to be were it not for some other nature and culture, is a monkey’s paw kind of wish, best not granted and thus perhaps best never called for.

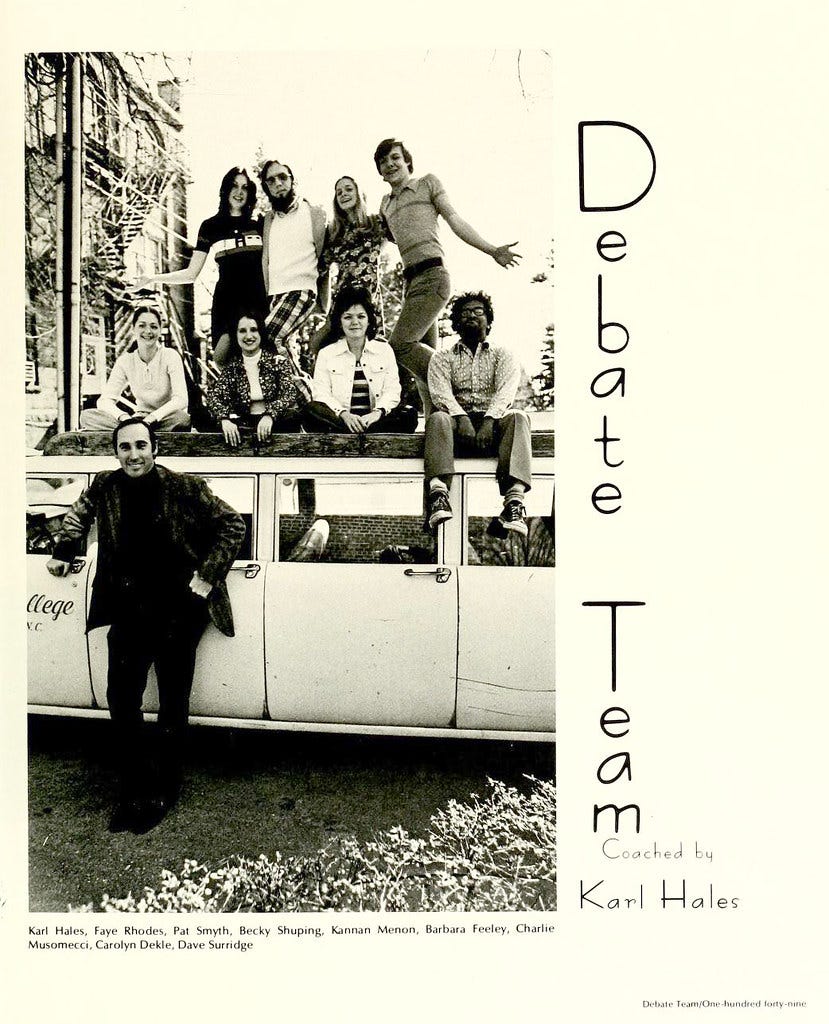

Image credit: "Catawba College Debate Team, 1974" by North Carolina Digital Heritage Center is marked with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.