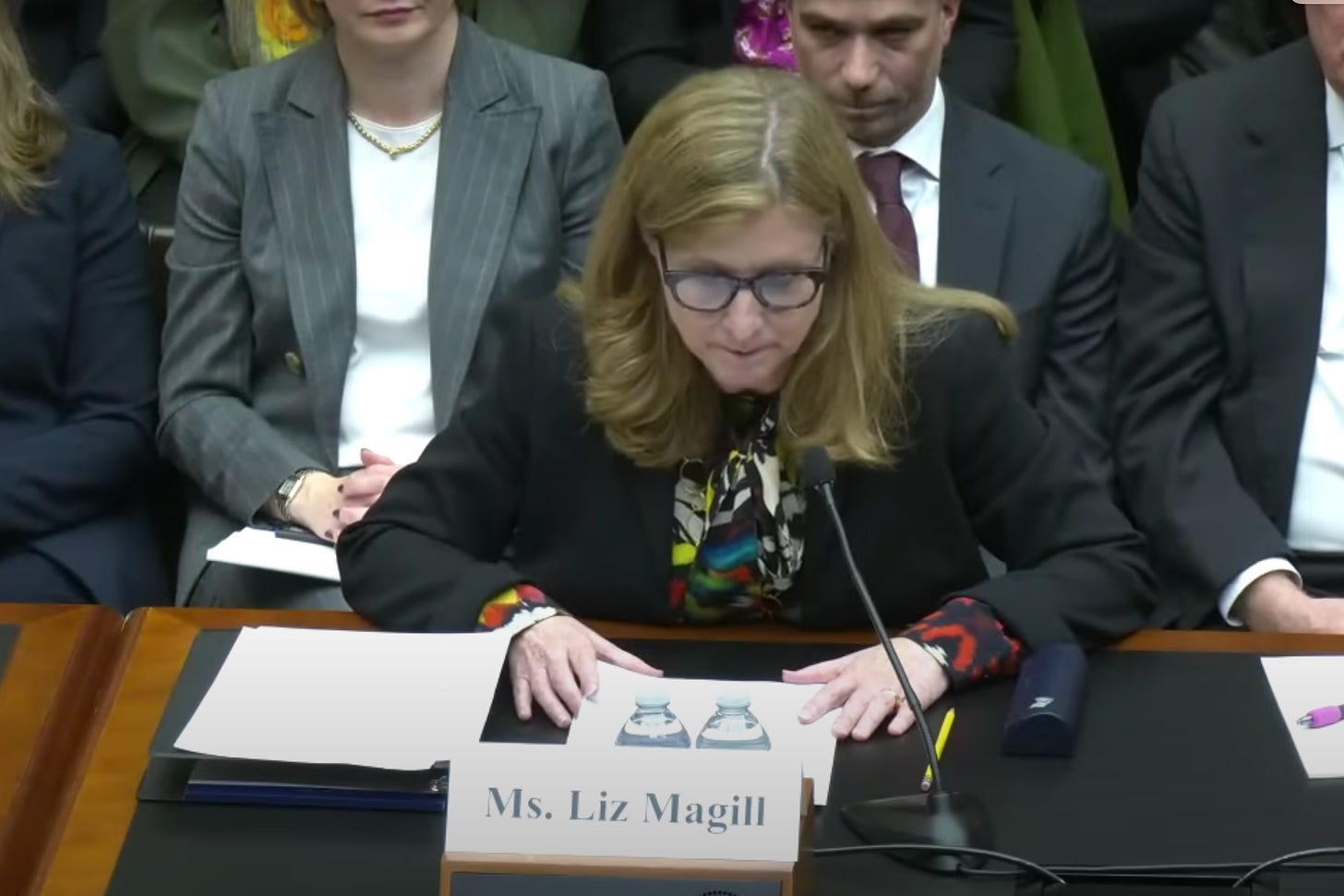

So there seem to be some opinions out there about the university presidents called to testify before Congress about anti-semitism on their campuses. Perhaps to the point that one of them is going to be asked to resign.

Let me contribute a bit of context that is mostly missing from mainstream reactions to the testimony. Basically I think almost all university and college presidents would have stumbled in that hearing, even if the issue were different. Most of them are extremely unpracticed now at communicating in situations that aren’t one of two things: intensely controlled or entirely predictable.

I’ve remained fascinated ever since I heard from a member of my family who was a political appointee about a form of preparation for Congressional testimony wherein one’s staff assembled a “murder board” designed to run the soon-to-testifier through friendly questions, slightly-skeptical questions, predictably hostile questions, and then every freaky or unexpected question the staff can think of.

Higher education leaders do not generally get their staff to run a murder board for them in preparation for any meeting or speaking engagement. They certainly get a briefing before talking to donors that rehearses expected questions and warns against known triggers. They get advice about planned communications, perhaps sometimes from people who might offer an advance look at skeptical or negative responses. They frequently discuss potentially fraught or difficult meetings with a small handful of advisors or senior staff. But most presidents, chancellors, provosts, and deans either know better than to step into an unpredictable, high-emotion setting full of potential hostility or they learn the hard way after doing that once or twice never to do it again.

What they know, however they’ve learned it, is to send intermediaries into the more fraught situations, or to simply avoid them entirely. It’s relatively easy to be too busy at need, to delegate as a sign of seeming respect for the delegatee (while more or less knowing it’s hanging someone out to dry), or to insist on process and incrementalism as a way to wait out a potentially unrehearsed conversation or appearance.

This would go generally for a lot of heads of organizations, including corporations, but I think higher education’s structures for managing communications and controlling conversations are more comprehensive, in part because they dovetail into general ideas about civility, decorum, consensus and process that are more generally shared within the professional environment of most universities and colleges.

So, again: unpracticed.

The other reason I think those university presidents would run into grief in almost any adversarial appearance where they can’t tightly control the venue and framing has to do with the kinds of advice they get from their increasingly sprawling administrative staffs, associated consultants, and peer leaders. There are four controlling vectors that will push on any kind of conversation or undertaking that ties back to leadership.

The first and most powerful these days for any institutions that have sizeable endowments and other forms of wealth is above all don’t get sued or audited. Minimize liability, protect the nest egg. That means that compliance is the holiest of commandments and that nothing should be said which might either encourage a lawsuit or provide ammunition to one that’s already ongoing. Manage all risks down to their existentially-minimal state.

The second is “preserve and extend all forms of formal and informal discretion for futureward administrative action while compressing the discretion of other actors within the institution; decrease transparency of executive action while increasing transparency requirement outside of it”.

The third is, “deflect intensifying attention on a particular issue to other actors within the institution, to wider communities, to the society at large, to the world we live in; take no sides that cannot be attributed either to legal obligations or qualified into generalized equanimity. ”

The fourth is, “diffuse and manage any damage—absorb grievance into process, promise future responsiveness, invoke the possibility of agility or flexibility, practice allusive and indirect forms of acknowledgement, embrace the vague”.

Even leaving aside Congressional testimony or other high-stakes public discussions, these conventional pressures on academic leadership often have perversely opposite outcomes from the intent. Risk management that is attentive only to compliance and liability sometimes amplifies risk precisely because the people providing that advice don’t bring either politics or emotions into the frame of their reckoning. There are moments where direct speech and honest acknowledgement do more to check escalation than passive-voice evasiveness and legalistic framings, where human and humane engagements win the day and proceduralism loses it.

Outside of the culture of manners within academic environments or professional work cultures generally, these impulses are even more likely to blow up in the face of the person counseled within these guidelines. They read as evasive, as waffling, as confused, as indecisive.

That’s what happened in this testimony. These impulses prevented these presidents from saying with absolute clarity, “we’re against anti-semitism generally, and against it absolutely on our campuses” in a way that scanned as personal, committed, emotionally real and substantively responsive. That is just not the culture of leadership in this country at this point, higher education and otherwise.

Except, perhaps, for the worst of our political class and a segment of the punditry, who have no such limits. So that’s the other problem here, which is that even if university presidents had murder boards and they got better advice about how to communicate across a broader spectrum of situations and they understood “risk” in a more holistic way, it still would have been right to come to a stop when Elise Stefanik said, “I have a loaded, bullshit and entirely insincere line of hypothetical questioning here that I’d like you to answer to, because I’m setting this up so you either look shitty on this issue or you look shitty as a university leader who is actually doing the right thing in your own institution.” There may be ways out of that trap, but just saying “I’m against anti-semitism on my campus and I promise to expel anyone who says anything bad! Thank you, Congresswoman!” isn’t it.

I’m sometimes skeptical of FIRE’s framings of free speech on campus, but they’re correct in saying that the difficulty these presidents are in also has its roots in the contradictions within typical campus policy infrastructures on speech, harassment, harm, and safety. I’m not sure that the simplification that FIRE suggests resolves out the complexities, though it does a lot to unknot some knots and is worth considering as a direction just for that reason.

But let’s walk through this complexity in reference to one of the common sentiments that is being misused by insincere political actors like Stefanik.

Suppose a student on a university campus says, “Palestine should be free from the river to the sea!” Stefanik and others (including some trustees and ex-trustees at certain universities) clearly want to have this be regarded by policy as anti-semitic and to lead instantly to the expulsion of a student or to the termination of an employee.

It is not waffling or incoherent to say, “What’s the context we’re talking about here?” (That’s the problem with answering a hypothetical without taking control of the framing structure: the hypothesizer can just say ‘I have a different scenario in mind than the one you’re describing’ endlessly to refuse the scenarios you lay out for them.)

Who said it? Said it where, under what circumstances? Said it how?

If I were in a classroom dialogue or speaking directly to someone who just said the slogan, I’d ask, “So what do you personally mean by that? ‘Free’ in what sense? Are you talking about a single democratic state with constitutionally provisioned rights, and within what borders? Just the West Bank? All of the territory that is presently claimed by Israel plus Gaza plus the West Bank? Are you talking about a Palestinian ethnostate that would expel most or all current citizens of Israel? Or would you accept the accusation that you are calling for the killing of most of Israel’s current population?”

I’d ask those questions not because I’m waffling but because that’s what we’re here to do. Just as the purpose of Congress increasingly seems to be to let cynical buffoons waste money and time, our purpose remains to think and learn together.

Suppose my hypothetical student or colleague replies, “I mean a single state with constitutional rights”, our dialogue could go on for a long time. We would be part of a long-standing real dialogue that has included many people of unmistakably good will who are in no sense anti-semitic. I’d ask if my conversational partner understands why many Israeli Jews as well as Jews outside of Israel and many supporters of Israel regard a single state solution as a threat to the safety of Jews in Israel and arguably everywhere, why having a specifically Jewish state as sanctuary and refuge is important to them. I’d ask why they think constitutional protections would work given the depth of antagonisms within that new state. I’d ask how they plan to handle the possible restitution of Palestinians returning to this new country, but also how they plan to respect the property rights of people currently residing in Israel.

But none of these questions would require me to regard the other person as an advocate of genocide. At best I might suggest to them that they may seem indifferent to real and well-founded fears of genocide or violent reprisal in advocating their solution. I might also argue to them that the slogan they’re using is a pretty lousy way to communicate this more specific vision of a future.

But I’d also have in mind that it is simply not true that questioning whether the state presently known as Israel must be an exclusively Jewish ethnostate is either definitionally anti-semitic or definitionally genocidal. No nation on Earth gets to set rules that way about its own existence in its current form. I am allowed to wonder whether Senegal and Gambia should not be one nation instead of two. I am allowed to wonder whether Biafra was a legitimate idea. I am allowed to question whether the creation of South Sudan solved anything, or whether the partition of the Democratic Republic of Congo might not be a reasonable way to deal with some of its perennial problems with cohesion. I am allowed to ask whether there are other ways that states formerly ruled by European empires might have been created during decolonization. I am allowed to look at the creation of Nunavut and wonder if it is not a model for other indigenous-rights movements. I am allowed to wonder whether American federalism in its present form is corrosive, just as some people of eastern Washington state are allowed to imagine the creation of a “Greater Idaho”. I can listen to a Sikh separatist make a case without doing harm to India and I can listen to a representative of the Indian government explain why that must never happen. It is in fact a reasonable question of supporters of Israel: why must it be perpetually Jewish? And to ask whether, if the answer is, “For the security of world Judaism” whether that might not be a flawed answer. And whether that commitment doesn’t put Israel as a state on a collision course with violations of humanitarian principles if over time it actually does annex the West Bank or Gaza, if it didn’t doom Israel to that violation from the first moment? These are ideas that we have to be allowed to explore, conversations we have to be allowed to have without fear.

If my conversational partner says, “I mean expulsion of most existing citizens and residents of Israel or to allow their residency only as second-class citizens with minimal rights or prerogatives in this new state”, then our conversation is shorter. If it’s a classroom, I do my Socratic best to get a student to think more deeply, more complicatedly, to see the practical and moral problems with what they have said they mean. I try to make sure I’m not enforcing my own orthodoxies as a criteria for evaluating the quality of their work—but I also don’t just accept a slogan and a troubling explanation as if it were an adequate engagement with whatever we’re studying. If it’s in another venue, I’m not sure I bother much in pushing back on this dangerous, unjust, and almost necessarily violent idea. (I might try to point out all the other circumstances where I suspect this person would absolutely reject this as a valid approach to political belonging—and hope that I don’t find out that I’m talking to someone who is in fact a general proponent of that kind of sociopolitical hierarchy within nations.) Do I want this person reported? No, unless they insist on hounding me about my opposition to their advocacy or I see them doing that to someone else, because then we’re not talking about a disagreement or a question of speech, we’re talking about personalized harassment, which is different. If they’re personalizing it—if they’re saying, “I want you and people you know expelled, humiliated, hurt, and I won’t give up yelling my slogan at you until that happens”, we’re in a new arena. But otherwise, I suspect there’s not much grounds for an ongoing conversation: this person’s working foundational ideas are very different than my own.

If my conversational partner says, “I want millions of people murdered, yes, you heard me right, that’s what that slogan means to me”? Then we are also in a new arena. If we’re in a classroom, well, I’m not having anybody seriously advocating that kind of action in front of me in a classroom, period, free speech or otherwise: that’s simply failure. I cannot imagine a course I would design or supervise where there would ever come a moment for a student to say as a legitimate response to a prompt or discussion theme, “I am in fact in favor of mass murder”. If I’m in a conversation in another venue, the conversation is over, and yes, I am wondering what I do next, much as I would if I was talking to a student or colleague and they said, “I’m considering murdering people in the house across the street”. That’s not “free speech” appropriate to an academic environment where people are both studying together and living together.

You’d think it would go without saying that this applies in the other direction, e.g., the person who says, “I hope a million more people die in Gaza, keep them coming” has failed any class prompt I can imagine building, is just as much a person I need to end a conversation with, but I am not sure that some of the people hectoring higher education think quite that way—one reason for what Marc Lynch and Shibley Telhami report about faculty self-censorship on the Middle East and how more faculty who see themselves as sympathetic to the Palestinians are inclined to self-censor than otherwise. It may be otherwise among students at a number of campuses, certainly.

If all that sounds like a bunch of evasiveness, then you’re not a good reader—or you’re reading with malicious intent rather than a desire to engage. I actually think those university presidents and their peers have good intentions on this issue, and are being mindful of exactly what I have described here. I think that if they struggle to communicate some of this, that’s because they struggle to communicate almost everything in their work, surrounded as they are by habits of indirection, vagueness and evasiveness. I often wish that wasn’t so for a great many reasons, but I especially wish it when it comes to moments like this, where some plain-speaking about the genuine difficulties of thinking and living together could potentially do important work.

Tim, excellent, insightful, something I’ve been trying to get my head around. Much appreciated.

This long response was eloquent, especially your contention that our seriously restricted terms for thinking through national and international policies were killing off broad questions that ought to be asked.. I laughed silently to myself when you questioned speculatively whether "look[ing] at the creation of Nunavut [one would] wonder if it is not a model for other indigenous-rights movements." It seemed a partial extension and answer to the previous speculation, "I am allowed to ask whether there are other ways that states formerly ruled by European empires might have been created during decolonization[?]" ---I relate those questions to the pluralistic political philosophies of James Tully [former McGill University professor] and Charles Taylor [McGill Emeritus]. I'd especially call attention to Tully's _Strange Multiplicity: Constitutionalism in an Age of Diversity_, which begins with the [currently, much disputed] claim that North America's Constitutional frameworks are clearly progeny of Northern Europe's ideal of 'living constitutions'. A Charter of Rights and Freedoms based on a premise of evolving constitutional negotiation granted special sovereignty to provincial Quebec and also to Nanavut would be a proven, practical basis for reconsidering the status of states---little nations---within the Federal Nation. **I wonder whether contractual law in the U.S. has enabled corporations to become obtain those 'special sovereign' [constituent nation-]statuses in the 'service' of the market economy.** So Tesla and Amazon [like Haliburton before] practically become the U.S.' shadow-living-constitution's 'First Nations'. 'Pretty 'screwed-up, when another way of seeing our country's pluralism might consider a Greater Idaho and also a Sovereign State of Atlanta.)