Now for student protesters and their closest allies inside and outside the university, who I think need to be adaptable, smart and reflective at this moment of extraordinarily high risk to them, their institutions and the country.

My general argument here: normally stop imagining protests on campuses to be necessarily about demands for action from colleges and universities except that now they have to be. I’ll come back to that point later.

Let me start with some simpler or more focused observations that are about the direct state of protests right now.

First, even if the protesters want to stay focused entirely on Gaza and Israel and not expand their focus, drop divestment as a demand to universities about their endowment funds or other investments. If you think everything else in this column is unhelpful nonsense, do me the courtesy of thinking this one point through. Divestment made marginal sense at best as a pressure strategy way back in the anti-apartheid movement, but ever since then has been less and less coherent as a tactic. The primary reason is that the nature of investment itself has changed so dramatically. Universities don’t own stock of particular companies for a long time now: most of their endowments involve frequent trading and in a much wider range of asset classes than stocks. Their investments are also frequently firewalled off from direct scrutiny by administrators, who are not kidding when they say they don’t even know what the endowment actually owns on a given day. Moreover, publicly traded companies largely could care less whether some group of potential buyers are not buying their traded stock, and mostly you don’t have shareholders who bring pressure on companies if the stock value is falling. Even when you do, boards and CEOs might ignore that pressure. Excluding companies from a list of assets an endowment can own doesn’t hurt them in any real way, and they are the real targets of a divestment campaign.

This doesn’t mean that you can’t bring meaningful economic pressure on some companies, but it’s not via divestment or other forms of shareholder activism. If you want to bring pressure on some companies, call for a boycott. (Which in fact is a strategy of the larger movement.) In many cases, that can just be about persuading students to alter their consumption on campus and beyond and doesn’t even require the university as a partner.

As a side issue, I understand that some of the companies that provide critical support for the Israeli government aren’t the kind that you can target with consumer boycotts, so the secondary strategy is to also bring pressure on the federal government to limit or constrain some of its interactions with the Israeli government and to push companies to align with that strategy. That is a perfectly normal thing to do in policy terms—the US government maintains constraints of that kind in the case of China, Russia, Cuba and other states. Moreover, as is now obvious, the current administration is, or at least ought to be, exceptionally vulnerable right now to political pressure from possible voters. I get that everybody is screaming at the protesters that the stakes are too high right now vis-a-vis the November election but that’s a great moment to strike a real bargain: the protest leadership should absolutely promise to deliver votes in the fall, to become a powerful mobilization machine, if some basic demands are made (US demands immediate cease fire or it withdraws military support and backing in the UN; US demands immediate negotiations towards a two-state settlement or it withdraws military support, etc.) Though unfortunately the Biden Administration seems as tactically inept on this point as it is generally when it comes to positioning itself for a crucial election.

Second, stop expecting colleges and universities to declare that as an official act, they endorse the moral or substantive claims of your movement or any other movement. Much as it has turned out to be a bad idea to overstate safety and security as the primary justification for paying institutional attention to claims of discrimination, harassment or exclusion, it would be a bad idea to demand that universities begin to designate a variety of specific sociopolitical commitments beyond vague philosophical principles that relate to their core missions, because that would become yet another battleground where progressives in many states might lose battles. The neutrality of the university, however partial or phony it might be at times, is potentially a source of protection.

Moreover, much as in the case of divestment, this is going to be an issue that administrations fight to the death on anyway: the energies you’d have to muster to get a bog-standard private university to say, “We are officially against X; we officially support Y”, where those positions are not directly relevant to the welfare of the institution are likely beyond any movement—you’d have to more or less have near-total mobilization of the student body and a willingness on their part to unenroll and go elsewhere, with a confidence that no other group of applicants would take their place. You can demand commitment to zero waste or carbon neutrality because they are directly relevant to the bottom line and to the institution’s existence in the world, but not to supporting the independence of Biafra. Where issues manifest inside the campus and there is legal room to maneuver—gun ownership, reproductive rights, admission of undocumented students—you can bring pressure and hope for good results. Where they are distant or there is no legal space, you can’t.

The reason for that is partly that colleges and universities in the US are 501 ( c ) 3 non-profits, which is very important to their budget models. Administrative leaders tend to overinterpret that status as meaning scrupulous and total absence of official political advocacy, often to their own detriment. (There are plenty of non-profits outside of higher education with that status that engage in open political advocacy of some kind.) More importantly, it’s a threat to the professional careers of administrative leaders. Gaza protesters at private institutions have to understand that if they somehow miraculously achieved a demand that their presidents or deans officially commit the institution to opposing the current government of Israel’s actions, they would guarantee that those leaders would be fired within 24 hours by their trustees except at a teeny handful of institutions. I sort of think students at public universities understand this point already. If they didn’t, they’ve surely learned it in the last two weeks.

Third, protest movements do need to discipline themselves somewhat. I’ve been arguing in the comments of my previous essays here that this is something of a sucker’s game to play in the sense that all protest movements face endless demands that they get rid of the supposed extremists in their midst. Many of those demands are insincere in multiple ways: the goalposts will be moved no matter what you do, the people demanding this as the price of their endorsement or participation will never really join or support the protests. Or the movement will become so anodyne and unfocused in pursuing acceptability that it will no longer be pushing for any change at all. You can march for universal love and peace among nations and say only nice things and that will be a meaningless act that wastes everyone’s time.

Do it not to satisfy those who will never be satisfied, but to have enough structure in a movement so that you can exercise authority over what you do collectively and you can disassociate yourselves swiftly from what you didn’t do or didn’t agree to undertake. That’s democratic: the body of the whole has to be responsive to the majority that constitutes it, and to be able to have knowledge of itself. Having a movement where everybody’s free to say and do what they like eventually means you either don’t have a movement or you have a movement that a tiny fraction of the whole can appropriate from everybody else. We have to try and live into the world we want even as we’re still stuck in this world.

There’s also no reason to fixate on particular slogans other than to show that you can’t be stopped from saying what you want to say. Folks have a problem with “from the river to the sea”, fine, who cares? Drop it. Doesn’t matter if they’re insincere in saying that and what they really mean is “I have a problem with your advocacy of sovereignty for Palestinians”. Be adaptable, be protean. And be local: the content of protest should seem to belong within a particular campus rather than consisting of a bunch of citations from elsewhere. I actually studied South African history as an undergraduate but when I just let ANC slogans flow through me, I wasn’t being as effective as I might have been in my participation in the anti-apartheid movement on my own campus. I was accepting a model of the ANC’s right to be a sovereign-in-exile, accepting that they were the only legitimate authority for what South Africans demanded and what South Africa should become, without being aware in some sense of the propositional ideas underlying those claims.

Fourth, don’t do dumb shit. Yes, I mean whomever spray-painted slogans onto concrete on my own campus and similar kinds of things elsewhere. Don’t do things that have almost no purpose that also hand your opponents a ready-made reason to suspend you or prosecute you. The most sympathetic dean in the world is going to have to see spray-paint as vandalism and act accordingly.

Let me return to the big point I started with. These protests should have stopped being about colleges and universities except now they have to be about them.

What do I mean by that?

All the way back to the anti-apartheid movement, the weakness of campus activism has often been that it gets drawn obsessively into demanding that the institutions act as allies within larger struggles against distant or well-protected adversaries. This structure of protest has turned colleges and universities into proxies for those targets and eventually replacements for them, because protesters accurately perceive that they have some hope of minor concessions or that they will at least be able to compel the authorities on their campuses to listen to their demands, with whatever legitimacy that provides. Effectively, protesters come to hallucinate that their university administrations ARE the bad guys they want to attack, and equally completely miss out on understanding what is wrong with those administrations.

The obsession with making the university knuckle under to a particular demand trapped campus activists in a cul-de-sac of their own making, where superior options for change were scorned because protesters wanted to hang a particular kind of trophy head on the wall. My colleagues here know that was my position on fossil fuel divestment for years, and I feel fairly vindicated on that point. I warned students that they were going to get stuck chasing an action that would have zero impact even if their demands were met, that was premised on a really poor reading of how to bring meaningful political pressure on the U.S. government to end subsidies for fossil fuel production. In the meantime, lots of possible actions that would directly commit universities and colleges to the goals of climate activism were scorned as distractions from the divestment effort.

What the Gaza protests have revealed, however, is first that there’s been a change in the internal architecture of power on campuses and that this change is now allowing external actors to directly intervene in university and college affairs in new and largely unaccountable ways. Moreover, I think those changes are aligned with the larger remapping of U.S. politics and social life to new forms of oligarchy. Now the issue really is the administrations and I think for the first time in a while, student activists understand why that is.

It’s fair to say that on some level this now means that the Gaza protests are no longer necessarily serving to direct attention to Gaza. I think that’s nothing to apologize for. If these protests are revealing crucial fissures within higher education—and in the wider society—it is fine to make that shift. In fact, it would be a good idea. The crisis in Israel and Palestine will remain relevant and important but the protesters should now be focused on what they’ve managed to reveal about their lives right now and their immediate futures, on what they’ve learned about the true nature of governance on campuses and the relationship between their universities and a wider range of institutions.

So what I suggest is that right now and immediately at the start of next fall, student activists should call the bluff that many university administrators have made in their passive-voice statements in the past week. If universities claim to support reasoned disagreements and debates, if they really do believe in learning together, if they embrace diversity of thought and experience, then turn the encampments into open air teach-ins, 24/7.

Make them expressly about conversation, debate and education, and not just about Gaza. About all the things that matter that aren’t highly prioritized in most university curricula. Let a thousand flowers bloom! The encampments should be alive with people talking about the flaws of nationalism generally, or about the reasons they support nations as a political form. About socialism, capitalism, anarchy, authoritarianism, about what has been and what might be. About political change and how it happens—or fails to happen. About the way the world got to be as it is. About why the curriculum is organized the way it is and what it could be. About pedagogies. About labor markets past and future. About oligarchy and hierarchy. About bodies and rights. About power and helplessness. About violence and peace. And none of it with fixed, hardened ideological positions. Explore. I think this generation is ready to make its own theories, conduct its own observations from what they’re living and what they hope to live.

Turn the encampments into makerspaces. Publish writing, formalize theory. Create art, stage performances. Experiment.

Reverse-engineer end-state political positions that people scream at each other, work back to first principles. What do we mean by freedom? What is unfree in our world? What do we know and how do we know it? How do we live and what do we want to live? Who are we here, who is not present with us, what is local to us, what is far away?

Make the encampments into what universities claim they want. Call their bluff. I suspect, as I’m sure most protesters do, that this will reveal that what they say they want is not what they want, and that encampments will be forbidden regardless of what they are actually doing, now that the gloves are off and the police have been called. So make wildcat encampments in this spirit! Flash-mob conversations, have spontaneous teach-ins. Be mobile. Force administrations to try to suppress what is central to their mission and values, to reveal that control and power have supplanted those goals. The most powerful defiance is doing what they claim they want you to do.

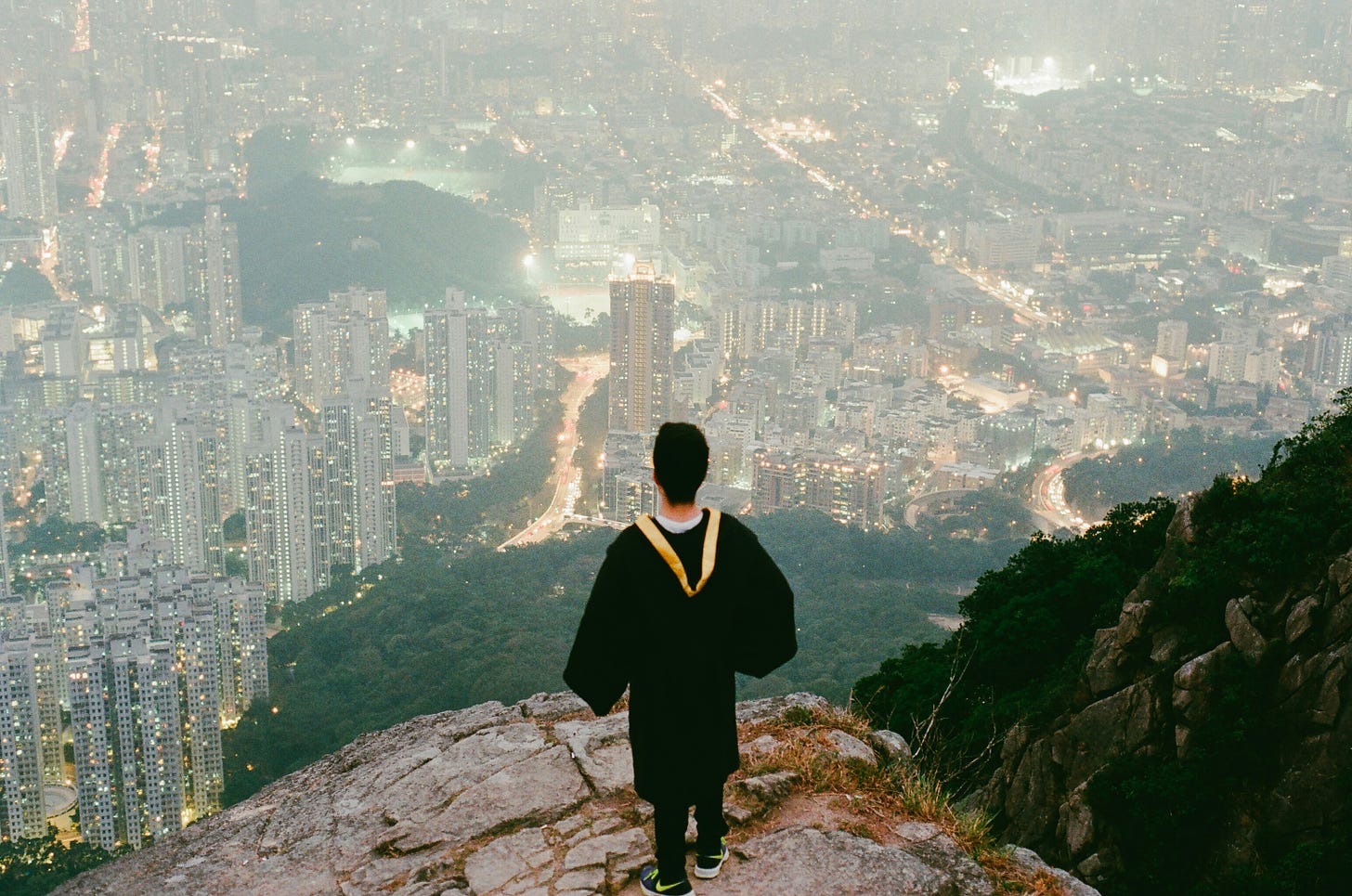

Image credit: Photo by Joseph Chan on Unsplash

Thank you for this insightful piece, particularly the way the university itself serves as both antagonist (as avatar of “the man” or “capitalism” or whatever) and simultaneously supposed ally (and therefore in some cases *traitor* to whatever the movement’s goals).