Part of me has a hard time thinking my way into the debate about Randy Barnett and Ilan Wurman’s argument that the jurisprudence on “birthright citizenship” derived from the 14th Amendment is incorrect and that it is perfectly plausible that the citizenship clause should be read as meaning that the children of people who entered the United States illegally should not be regarded as citizens.

Legal scholars have already ripped this argument to shreds in its own terms. It also fails a broader conceptual test, because if you take Barnett and Wurman seriously, then most American citizens today are not citizens, e.g., anyone who is the descendant of people who came into North America without the explicit legal permission of the constitutional republic is not a citizen. Considering that the United States didn’t have a comprehensive legal framework for awarding or denying citizenship to new arrivals until 1875, that’s a lot of Americans—pretty much everybody whose ancestors showed up between 1800 (after the initial Naturalization Act) and 1875.

But Barnett and Wurman are just trolling, I think. I’m not even sure why they are bothering, because legal interpretations seem to be already close to irrelevant, especially in Supreme Court majority arguments. If Alito doesn’t find what he wants in the Constitution, he just goes dumpster-diving in medieval legal codes. The SCOTUS majority doesn’t care what the Constitution says, what the law requires, what precedent suggests. If they do find against Trump at any point, it will only be because they have some other instrumental end in mind. At which point they may find that they have empowered a tyrant who doesn’t care what they rule in any event, and will obey no constraint they try to place upon him.

Despite my feeling that Barnett and Wurman are going through motions that no longer matter regardless, that even bad-faith legal arguments that are factually incoherent aren’t needed as a fig leaf for destructive executive actions, I did find myself going down a related rabbit hole that went to an important point when a Bluesky user pointed me to a great methodological essay by the historian Jonathan Gienapp written in 2017 as a response to yet another badly formulated argument from Randy Barnett.

In the essay, Gienapp is working from a then-forthcoming book that came out in 2018, The Second Creation. The book’s central argument is that “originalism” as a conservative legal doctrine is wrong in understanding even what it purports to value, which is the meaning of the original text, because the Constitution was in the decade following its creation a deeply uncertain thing that meant many things, and that even the idea that it provided a fixed and primarily legal thing was the result of more than a decade of uncertain grappling with the idea of a constitution, with the meaning of constitutionalism. In conventional readings of the U.S. Constitution in the 20th Century, legal scholars and political philosophers frequently returned to the Federalist and Anti-Federalist papers to understand the intention of the Constitution’s provisions; Gienapp suggests that the fifteen or so years that followed its ratification are what really matters in this respect.

In the 2017 response to Barnett, Gienapp grapples with what he called “Originalism 2.0” and I think grants it more dignity and coherence than it deserves. “Originalism 2.0”, in this rendering, describes the evolution of Federalist Society-molded judges and legal thinkers towards interpreting the original “public meaning” of the Constitution rather than the original semantic meaning of the words in its text and the original semantic intention of its authors. E.g., what late 18th Century American publics thought the Constitution meant is what it must be taken to mean today. As Gienapp observes in his more recent 2024 book Against Constitutional Originalism, this newer turn in originalism seems to require historical inquiry that the judges and legal thinkers involved never engage in. They take themselves to be the measure of what late 18th Century American publics were. As they think and intuit, so must they have in the past. If you were going to be charitable (and I am not), this would be the logic behind some of Alito’s opinions in recent years—that those publics were understanding the Constitution via the previous century’s English common law, which he takes for granted informed their construction of constitutional meaning.

In his 2017 response to Barnett, Gienapp digs in hard on a point that most historians understand extremely well, which is that deciding how people made meaning in the past, in understanding what things meant to past people, is an incredibly challenging methodological and epistemological problem. Above all else, you cannot begin to make honest progress towards that work if you just decide that you’re the subject you’re looking for, and that what makes sense to you must have been how people made sense in the past. That’s especially true if you do it in the especially crude sociological way that the current originalists implicitly do—that the reason they can gauge those past publics is that they are also white, literate, educated people of means.

Gienapp’s basic point in 2017 was “don’t send a legal scholar to do a historian’s job” if they want to be a 2.0 originalist (much as literary scholars pointed out that originalism 1.0 took being a better reader of text and authorial intention than most legal originalists seemed capable of). Of course Barnett objected to that while demonstrating that Gienapp’s basic point was right: that Barnett and others in his camp had no intention of taking their own arguments seriously enough to do the work those arguments required.

If you want to think about this point without going deep into the research that Gienapp and other scholars have been producing for the last decade, I’m going to offer what may seem like a very silly comparison. What I hope is that this comparison will get at what’s at stake here in a readily accessible manner.

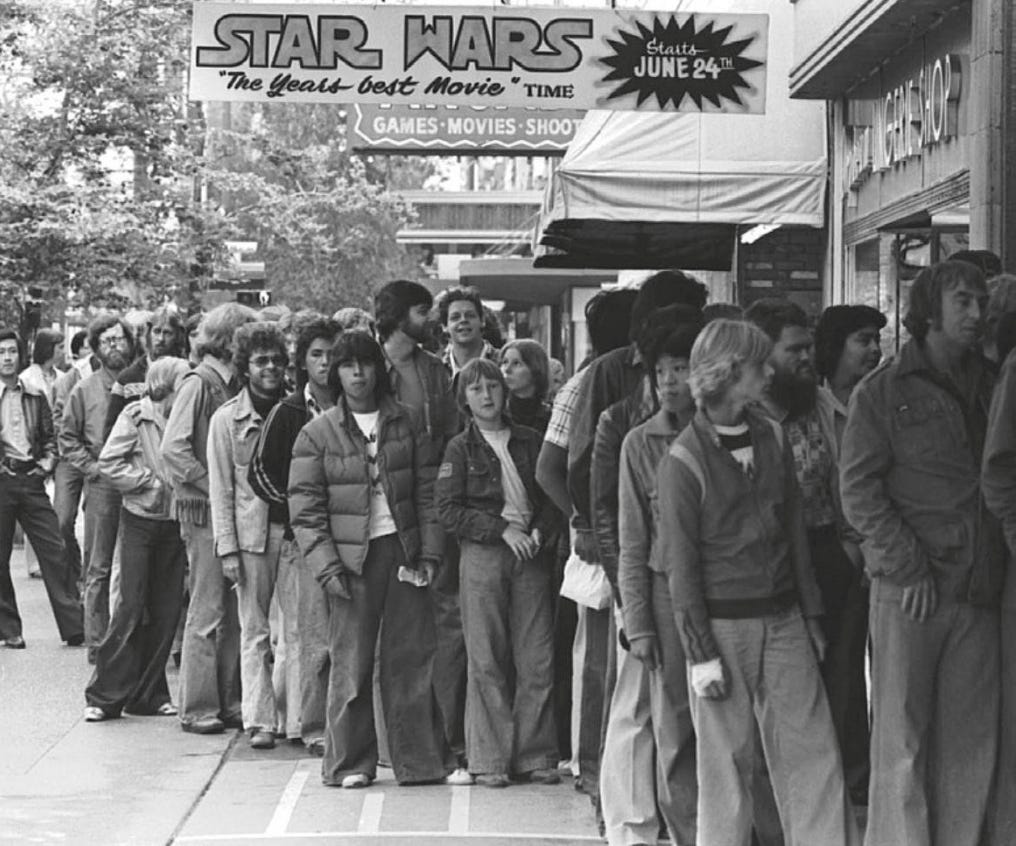

What does the entire body of culture associated with Star Wars mean to Americans who have been alive since the first film came out in 1977?

How would you go about answering that question? Would you sit down and watch all the films? In the order they came out, in the order of the narrative within the films? Would you read all the books and novelizations in the order they came out, or only the ones that are today “canon” according to the new owners of the franchise? Would you read the comic books too? Play all the games? Watch the Christmas special?

Would you read or watch every interview with the people who have made all of that culture? Read all the formal interpretations of the films by movie critics, read all the scholarship that has analyzed Star Wars?

If you did that, you would not really be much closer to answering the question I posed: what did Star Wars in its totality mean to Americans living between 1977 and 2025? If you decided to answer that question based on your own viewing of the cultural works involved and some engagement with the intention of its makers, you would just be substituting yourself for “Americans living between 1977 and 2025”. You would be saying “What it means to me is what it means generally”.

I watched Star Wars in the movie theaters as a young teenager about fifteen times in the summer of 1977. I’ve seen every movie since, most of the Disney + shows, read most of the comics, many of the books, dived into so many message board conversations, been to SF conventions. Wouldn’t I be justified in anointing myself the modal American?

Even if I were (and I think in a rigorous statistical sense I absolutely am not) that doesn’t answer the question. The meaning of a cultural text in a broadly constituted public, in a society, is not set by the people most devoted to that text. It’s not established on Reddit message boards or in film criticism in newspapers. In fact, it’s not singular at all. The meta-text of Star Wars doesn’t reduce or collapse into one generally understood public meaning at any point in the last 50 years in the United States.

Star Wars, the sprawling property, means something even to people who have never seen any of it—there’s a paratextual knowledge of the metatext that’s widely distributed. Almost everybody knows what a lightsaber is, that Darth Vader is a bad guy (who is Luke Skywalker’s father), that there are spaceships, even if they can’t name those things. If the “Imperial March” comes on the audio in a shop, everybody sort of knows what it is. There are people for whom Star Wars means not the text but the people who like it, who disdain Star Wars because of its fans or because it represents the destruction of a more serious kind of cinema or because it’s capitalist greed or because it’s Disney’s monopoly. There are people for whom Star Wars is a joke, a point of reference, a non-memorable cultural property, and no more important than that.

At the other end of things, there are people whose cultural life is very nearly built around Star Wars as a centrally constitutive metatext, who use it as a constant point of reference both in their internal psychological life and their sociality. But even in that world, Star Wars does not have stable meanings. It means something different to a devotee who is 18 and one who is 60, it means something different to the fan who cosplays and goes to conventions and one who writes fanfic and posts to Reddit. Where devoted interpreters congregate, they do not agree on the meaning of the metatext. There is a religious schism between people who embrace The Last Jedi and those who view it as heresy. There are those who say midichlorians were just Qui-Gon Jinn’s delusion and those who insist on their canonicity. There are people who like the Empire, not the Rebels. And people who did like the Empire until they watched the first season of Andor.

The people creating and selling Star Wars are not outside these publics—they are shaped by them, they are of them, they disdain them. They make up legends about what Star Wars means and how it came to be that seem untrue on further investigation. They have shallow and deep histories of reference shooting through the text. They turn to scholars who have stepped forward to authenticate Star Wars as having mythological and philosophical depth.

So it’s all very complicated, and this is a text which ostensibly is just entertainment that at its origins was presented as an upgraded form of a somewhat misremembered set of older cinematic and textual entertainments. It’s not as complex as a constitution or a religious scripture (or at least it wasn’t at first).

Ok? So now imagine trying to answer the question of what Star Wars meant in these fifty years to Americans but doing that two hundred years from now, in 2225. It’s already hard to trace the meanings of Star Wars in 1987, in the first decade of its existence—you’d have to track down copies of Starlog, to find archives of the Science Fiction Round Table at GEnie, to get records of SF conventions in that decade. You’d have to interview tens of thousands of people in all walks of life, and figure out how to get at what people who were alive then and are dead now thought it meant. My dad waited in line with me and my siblings in 1980 to see The Empire Strikes Back and was eager to know what we thought about Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker. You want to know what Star Wars meant, you have to find a way to think about him, and he’s not here to talk to you. To track 1987, you’d have to read a lot of newspapers, you’d have to look at the box office and see all the places that the three original films had shown. You’d have to have a way to peer inside of families and schools and communities, to trace real and everyday conversations. You’d have to think about what Star Wars meant to people who’d only had it explained to them, or who had only seen the one clip from each film that Gene Shalit showed on Today when he did his reviews.

That is already from the perspective of 2025 a big methodological ask. From the perspective of 2225, you would have to understand who we were in total—how 1977-2025 made sense of life in general, what kind of human beings we were. You’d need a way to think about people who weren’t speaking in the archives you had but who shaped what Star Wars meant. You’d need to know, somehow, that some people related to Star Wars as if it were the resurrection of Flash Gordon and some people related to Star Wars as a three-generation family ritual, an island in time that referred to nothing but itself. You would need to find a way to not think about what Star Wars meant in 2040 when Disney merged it with the Marvel Cinematic Universe and Darth Vader fought Wolverine.

That is assuming that in 2225 you had the then-local version of intellectual integrity and a commitment to a vision of historical method that was continuous with our own. I especially don’t assume the latter will be the case. But here in 2025, that ought to apply if you’re going to claim to be understanding what the Constitution meant to the people living and working in the new American Republic in the years after it was ratified. Gienapp’s research shows what that might look like, and it’s nothing like “Originalism 2.0”. More importantly, his intervention into legal debates shows that hard methodological and epistemological problems are hard, and that anybody who really wants to know something has to put in the time to doing it right. If they don’t put in that time, it’s generally evident that they do not in fact what to know what may in fact be knowable.

There’s a long and storied tradition of foolish people deciding that what their profession needs is for its members to try to ape what another profession does, poorly. Economics went significantly off the rails in much of the second half of the twentieth century when it started handing out Nobel Prizes to economists who put together complicated and elegant models that happened not to have any explanatory power in terms of, you know, the economy, and spit out absurd outcomes. It got back on the rails around 2008, when they recognized that the goal of economics shouldn’t be doing a mediocre imitation of what high level mathematicians and physicists do, but to explain and understand the economy.

Similarly, right wing constitutional interpretation of the last 40 or so years has become a kabuki theater of lawyers cosplaying as amateur historians, badly. Even setting aside the fact that it’s all a facade (the fact that the original public meaning of “arms” at the time of ratification of the second amendment was limited to front loading muskets and semi functional revolvers doesn’t make it into their jurisprudence), we should generally be of the view that professionals who root their practice in trying to do other professions poorly aren’t very good at their own professions.