There have been times where I’ve been STEM envious.

Not because of resources or general social prestige, nor because of the strong shift of student engagement in their direction. Overenrollment is in fact the same crisis as underenrollment, and both of them are unpleasant and unenviable states to be in.

I might be envious a bit simply because I really like the things that STEM faculty study and the work they do, and sometimes wish I’d dug in more on math and science to test whether I could do that kind of work despite not having an instant facility for all of that.

Mostly, my envy has been a very specific thing, which is that when I talk about the unstable, delicate, sometimes precarious balancing act involved in pedagogy and in scholarship in a field like mine, a lot of STEM colleagues will listen and say, “Wow, I don’t really have to deal with anything like that.”

I have to think hard about how to create space for a student who quite reasonably articulates a position that African history shouldn’t be vested in the American academy, or that a white American who grew up in a professional upper-middle class household in a majority-white suburb simply can’t understand the substantive core of African history as a field of knowledge and a domain of experience and thus shouldn’t be teaching it. I can’t dismiss that out of hand: it’s a conversation I have to be willing to have. But I have to also create space for students who come to my classroom with very different intentions and views of the subject: the student who plans to work in international development, the student who believes in a straightforward way that all fields of knowledge are always open to all people, the Marxist who is openly opposed to a nationalist perspective or identity politics, the evangelical who is interested in the history of missionization, the budding historian who is mostly engaged with the methodological problems that surround histories of marginalized, colonized or subaltern populations, the student who has no priors at all but thinks maybe this will be interesting, the student who is interested in European empires but not so much African societies, and so on.

I have to teach the truth about the past and be open to all the things that may follow from that teaching: guilt, fascination, frustration, confusion, detachment. I have to teach that there’s no final truths in studying the past, that it’s all an act of interpretation all the way down, and be open to all the things that may follow from that declaration: acceptance, annoyance, evasion, cynicism.

I always feel one day away from misreading the conversation, from shutting down something I should have tenderly cultivated, from indulging something I should have shunted aside. I always worry that I didn’t hear or that I heard too much. That I came into a class from the wrong angle and missed where this generation is thinking and feeling or that I failed to bring to the current students the old insights that they are craving without knowing that they are craving them. That I make no sense at all, or too much of the wrong kind of sense. That I was flippant where I should be as serious as the grave, or serious where students have no idea what is pushing me to that tone.

Humanists and social scientists have known that the politics of the moment, the crises of the society, the conflicts raging across public culture, are always in the air we breathe. That we can only banish that from our work via an arbitrary dictate that surrenders our basic responsibilities, violates the integrity of our fields and specializations.

And so there are days where I’ve been envious of the thought that I might teach a topic or a technique and not have to think three or four times over what fires I might accidentally be lighting, where I could just focus on questions like did they understand and do they know how to do it now and do they know why this is important to this field and discipline?

That envy, of course, is based on a caricature of what it is like to teach in STEM, albeit one that even some STEM faculty indulge now and again. It’s true that when activists are aggrieved, when culture wars are being fought, when denunciations are being made, that it normally ends up coming at faculty in the humanities and social sciences first. I think we’ve all seen that the most urgently hated targets in the purging of universities that started in Florida and Texas and now threatens nationwide are not in STEM.

But STEM faculty have to think as much as any of us about the question of why what they are teaching matters and how to make the stakes of that knowledge transparent and motivating to students. They have to think about ethical problems that are hard-coded into what they teach and that attend urgently on how that knowledge is used and misused in the world around us. They have to at least think about questions of equity and access, to have a working view about who is in their classroom and why, and what it might take to shift the composition of that room. They have to ask whether it’s best to discourage students early who are unlikely to make it up the full sequence of work in a discipline or to support them in every way possible no matter how long and painful the journey might be. They have to ask what kinds of knowledge in their fields need the biggest and most expensive infrastructures directed towards them, and what needs to be known most.

It might be true, at least superficially, that there are right answers and wrong answers in the early stages of climbing up a STEM version of Bloom’s Taxonomy, whereas in a history class, maybe it’s never so clear. But far enough up the pyramid and everybody has to struggle with what is knowable and what should be done with what we can know.

I am not glad at all that the university, all of its ways of knowing, thinking and teaching, is under brutal assault right now from the destroyers who have seized the American government. I am not even slightly pleased that if anything, STEM fields are being more violently attacked, though I am still wondering if that was in any sense intended or is actually a diagnostic sign of how careless and incompetent Elon Musk and his gang seem to be. In this moment, nobody need be envious of—or secretly pleased by—the unequal distribution of our political burdens and our pedagogical challenges because they are falling on the entirety of what we do.

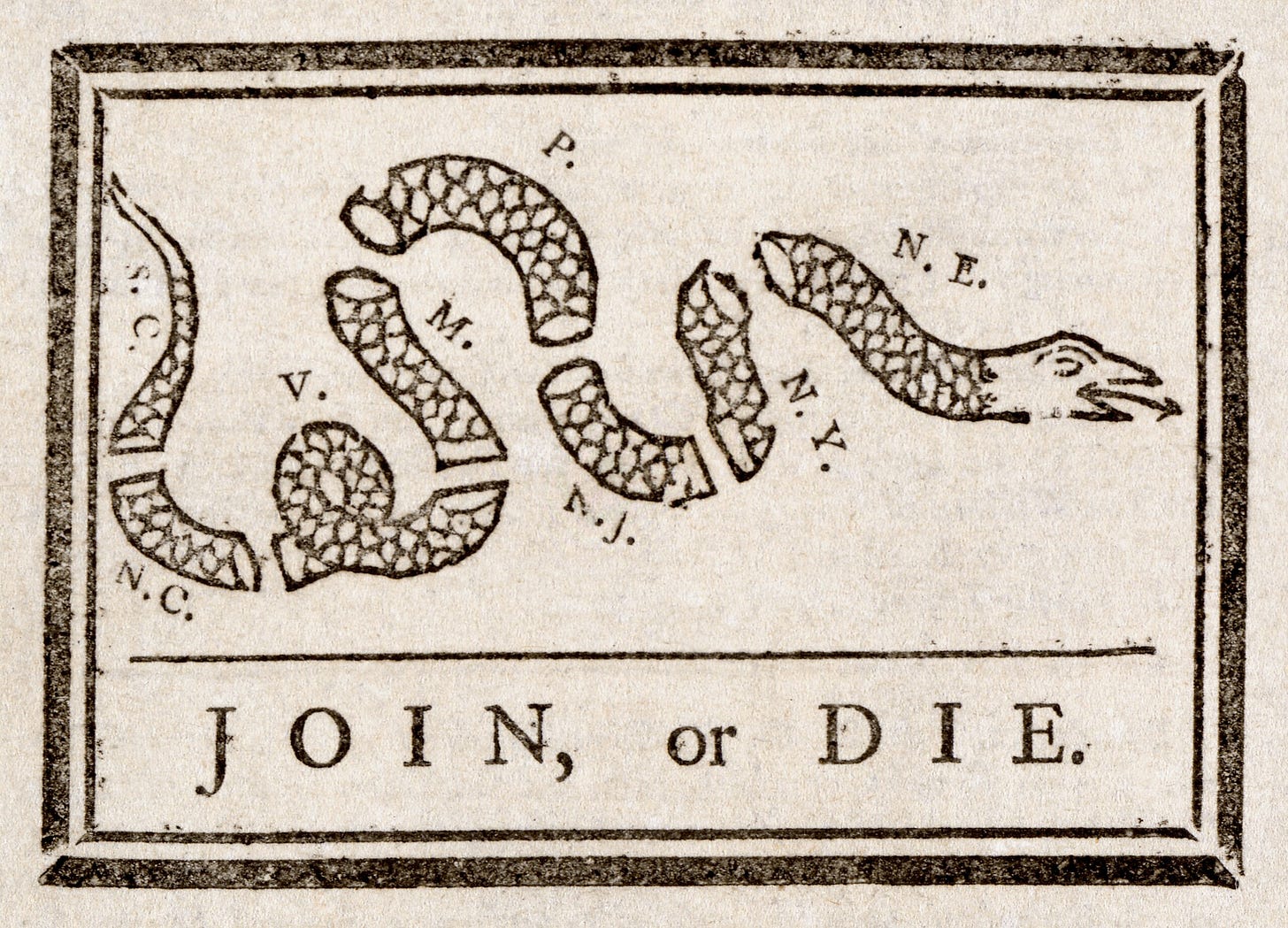

It may be nearly impossible to call together the normally fractured, divided, covetous and grudge-keeping faculties that inhabit most American universities and colleges. But in this moment, as we are put to the most severe test of our lives and the lives of our predecessors, we might find solidarity in the undivided enmity of people out to seize and destroy everything we do, all of us, indifferent to all our glorious variety and divergence.

Today, this is my valentine to all the professors out there, and to all the administrations that want to keep those professors teaching and studying, to all the students who want to keep learning, to all the parents who hope to see their children rise into wisdom and understanding through education, to all the citizens who see both beauty and truth in knowledge. I love you all. Let us recognize that if all of us might have our wishes dashed, it is because all of us share a common faith.

There’s a reason why invaders normally look to divide and conquer: because otherwise they may unite their foes and be defeated. Let us hope it will be so.

If it seems as if STEM fields are being more violently attacked, it's probably because historically they have been better supported by federal funds, making them more vulnerable to withdrawal of those funds and an easier target.

I can see how it might be reasonable to engage with someone who believes that African history shouldn’t be vested in the American academy, and does so from a position elsewhere in a different kind of vesting institution.

But somebody who has shown up in the American academe. They, presumably, have done so because they think that there is something of value in here, no?

And the lessons taught about education and discourse to other, onlooking students by tolerating rather than shutting down the "you can't talk about this; only I can" claim as an admissible power move—those lessons taught seem to me to be very poisonous.

Thanks much. Be as well as one can be in a world in which one is, personally, quite comfortable, but in which no man is an island. Yours,

J. Bradford DeLong

Professor of Economics, UC Berkeley

brad.delong@gmail.com :: @delong@mastodon.social :: @delong.social

+1 925-708-0467

http://braddelong.substack.com

====

Order Slouching Towards Utopia: An Economic History of the Long 20th Century, 1870-2010 <https://bit.ly/3pP3Krk>

About: <https://braddelong.substack.com/about>