Pamela Paul sets off in the New York Times to demolish a “ludicrous” and “offensive” argument that a gay Republican Latino would be better than a white progressive heterosexual woman at doing a physics experiment.

She is not quoting an argument that anybody actually makes in that fashion, but instead a caricature, intended to defend a paper that she believes is correct in its arguments and conclusions and should have been published in the journals to which it was originally submitted rather than in The Journal of Controversial Ideas: “In Defense of Merit”.

I’m going to spend some time with the paper itself. I think it’s pretty evident that Paul hasn’t really read it or understood why it might have failed peer review. For her it’s a means to an end, much as the article itself is. What I want to underscore is how a defense of science gives itself permission to be unscientific, that is, to make huge generalizations or offer descriptions which are at the least arguable both philosophically and empirically as if they are axiomatic (thus needing no philosophical defense) and long since proven (thus needing no evidence).

Those claims are essentially the Greek soldiers hidden inside a Trojan horse, which is a much simpler mustering of irritation and outrage at a set of administrative implementations of ideas, claims and scholarship that the authors of “In Defense of Merit” wish to substantively contest. Stick with those, and you’d likely have some sympathy for the authors—but you also likely wouldn’t have a peer-reviewed journal article fit for placement in a scientific journal, you’d have some other kind of written advocacy.

Let’s look at the abstract for “In Defense of Merit”.

Merit is a central pillar of liberal epistemology, humanism, and democracy. The scientific enterprise, built on merit, has proven effective in generating scientific and technological advances, reducing suffering, narrowing social gaps, and improving the quality of life globally. This perspective documents the ongoing attempts to undermine the core principles of liberal epistemology and to replace merit with non-scientific, politically motivated criteria. We explain the philosophical origins of this conflict, document the intrusion of ideology into our scientific institutions, discuss the perils of abandoning merit, and offer an alternative, human-centered approach to address existing social inequalities.

The paper that follows, sentence after sentence, paragraph after paragraph, breezily declares that long-running debates that go back deep into the Western tradition are just Q.E.D., beyond argument, no need to even pause and reflect. Most of the paper, and Paul’s defense of it, is a frantic running of victory laps after a match where the victor disqualified other competitors before the game even started.

Science, we’re told, “has generally granted humanity the gifts of life, health, wealth, knowledge, and freedom”. (All by itself, science did that!) Science gets the credit for “increasing literacy and communication”, and “science has promoted empathy and rational problem-solving, contributing to a global decline in violence of all forms.” Read that last sentence and you know exactly what the footnote is going to be: yup, it’s Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature. That’s a footnote meant to prove the accuracy of the claim that there has been a global decline in violence and that science is responsible, which isn’t even quite an accurate gloss on Pinker’s book, which gives as much credit to the modern state as it does science. But more importantly, that’s like me saying “The best cheesesteak in Philadelphia is John’s Roast Pork” and then giving as my evidentiary citation the URL for John’s Roast Pork. If you want to cite Pinker as evidence, you had better acknowledge that there are extremely substantial evidentiary challenges to Pinker’s claims in Better Angels, some of which have been collected in the anthology The Darker Angels of Our Nature. Historians have disagreed with how Pinker works with data: these are not “postmodernist” challenges or “identity politics” fueled rejections, they’re straightforward “No, the evidence you’re citing doesn’t prove that” and “No, the data you cite is flawed or just plain doesn’t exist”. That would go for many of the citations in the first sections of this essay: they’re colossal circle-jerks, ideologues citing ideologues as proof of their ideology.

None of the first three pages of “In Defense of Merit” are good science, nor good philosophy. It’s a declarative polemic of a kind that you can’t peer review as such. To actually demonstrate what the authors want to declare would take books. It has taken books. Books which end up treating every single one of these points about science and its accomplishments seriously and thus as arguable and complex.

What I particularly dislike about the triumphalist declarations of the first three pages is the prophylactic use of dismissive qualifiers, something that Paul also uses in the NYT piece. “Of course, science alone is not sufficient: science is but a tool that can be used for good and bad.” If science alone is not sufficient, then don’t write stuff like “science = life, health, wealth, knowledge and freedom”. Or “science = literacy”. (There’s a huge history of literacy, chock-full of evidence and facts, and the notion that it proves that science is the primary cause of literacy is not a common claim at all in that history.) Those qualifiers are intended as a pre-emptive defense against the complaints I’m making now: “oh, we agree that science is sometimes used badly”, “oh, we agree that there’s been cases of bias in science”. Really? Then why not take those points seriously enough that require actual discussion? With examples? When you hand-wave away the exception to the rule without further investigation, you’re announcing pre-emptively that no such exception will ever disprove your hypothesis about what science is and what science has done—which is a very unscientific thing to do, in terms of how the authors describe the scientific method. Normally the robust existence of exceptions is called “falsification” when it comes to a hypothesis—or at least as something that requires investigation in its own right.

Think about the proposition, which the authors (justly) celebrate, that the scientific method regards truth-claims as permanently provisional, always necessarily subject to skepticism, always open to the widest possible pluralism of epistemological and evidentiary challenges. And yet they also want to insist that science is purely objective, that it has nothing to do with subjective experiences, interior states of mind, or anything else of that sort, that it stands outside of being human in some fashion. Those two points are themselves in tension, and it’s not just “postmodernism” or identity politics that has created that tension. (The footnote on “postmodernism” in this paper is the usual laughable ‘the dog ate my homework’ kind of thing about how postmodernism is such a big topic that they can’t really be engaging any of it in particular: it’s plain that the authors just cherry-pick what they want ‘postmodernism’ to be from hostile third-hand summaries of it.)

Not only is this some of the deepest terrain of disagreement between many of the luminaries of the European Enlightenment, it also plays into a substantial body of contemporary cognitive science, e.g., whether or not we actually have some facility of reason that can think beyond or outside the limitations of our physical brains and our embodied nature. I’ve just been reading Ed Yong’s terrific new book An Immense World on on animal senses and the “Umwelt” of different species (and individuals within species) and in a pretty straightforward way, it provides a great example of where science done properly as the authors of “In Defense of Merit” wish it to be done fetches up some sharp limits on our ability to understand the objective truth of organisms with very different senses than our own. We can discover that they have such senses through scientific investigation, but our embodied subjectivity makes it impossible to really understand what that’s like (cf. Nagle’s essay on being a bat). Tell me that a tetrachromatic species sees colors that I don’t and I can believe the evidence. Tell me what those colors look like, and you can’t—and thus cannot really fully grasp objectively what it is to see like that.

Anyway. The authors of the paper would have been better off—and more likely to get published where they wanted to publish—if they dropped all the chest-thumping polemic of the first part of their paper and went right to what they’re really about, which is “merit”. That starts in about page 4. And you know, it’s a mess of an argument right out the gate because they conflate merit outcomes for scientists and merit outcomes for the results of scientific investigations in a way that suggests that they don’t even see the distinction—or why the entanglement of the two is precisely such a big issue.

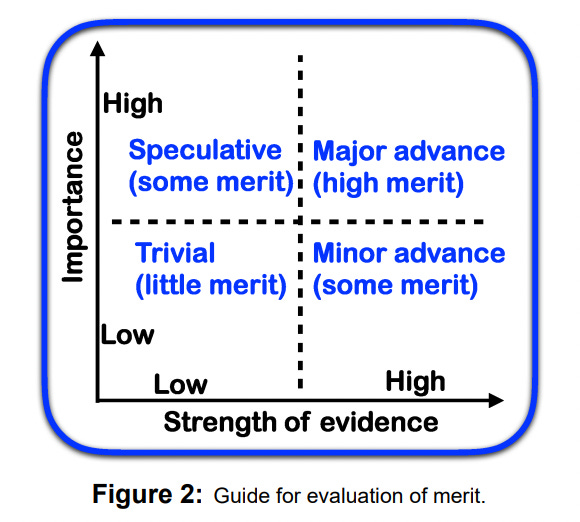

Here’s the figure they use to model the meritoriousness of the outcomes of scientific research:

Here we have something that is not really objective in some rigorous sense. (The authors know that, and acknowledge it more substantially than many other points that they hand-wave away.) In the actual history of science, it is not hard to show the following:

That ‘major advances’ often are not recognized as such until much later, and that the recognition of the magnitude of the advance is often dependent not on the work of the original collaborative team producing that research but on the collective labor of many subsequent researchers. E.g., what makes something major is often not sufficiently established by a single act of research by a particular team of researchers.

That many findings affirmed in the sociological relations of researchers within research institutions as “major” turn out later on to be not-so-major, or even to be quite wrong in a way that actually sends subsequent research down a fruitless path for a considerable period of time.

That “speculative” findings of “some merit” are also often not recognized as such until much later and that in many cases, the researchers making these speculations suffer professional consequences of various kinds because their work is derogated. Or that these speculations turn out to be meritorious only because they stimulate the speculations of a later researcher in ways that actually invalidate the initial speculation. Equally, it’s not hard to find “speculations” deemed as quite meritorious where that was at least arguably a result of the relative prestige and influence (and yes, social identity) of the scientist making the speculation.

That the other three quadrants actually depend upon the existence of work that is low evidence, low importance in order for their merit to be important. This is a familiar point about the centrality of negative results to scientific inquiry, but however familiar it might be, it’s not to be found here. And that’s because the authors are mingling the merit of research outcomes with rewards for the researchers.

Let us suppose that you could in fact reasonably sort all scientific research according to Figure 2, and grant that this would involve many judgment calls. You would still want to account for the observable, demonstrated frequency with which that sorting in actuality has not happened so neatly in the actual history of science.

A pretty good hypothesis for that might be that the sorting of outcomes is cited to defend merit-based outcomes in research institutions and in the wider political economy. Meaning, that researchers have strong incentives to manipulate the institutions that confer merit on outcomes and attach those outcomes to particular researchers. The authors of this paper don’t even regard that as a hypothesis worth testing, nor do they give much credit to numerous empirical studies that suggest that this might be so—for example, that many scientific and social scientific fields show evidence that authors are massaging data (often subconsciously) to move their findings closer to the upper right quadrant. That’s not just for the abstract desire to contribute work that is a “major advance”, it is that claiming credit for that work through a meritocratic institution translates into money and power, whether paid directly through that institution or in leveraging that credit into funding from granting institutions and financial rewards from claiming a share of intellectual property.

Ultimately, that is what the authors are really trying to defend: the awarding of status to particular individuals who are seen as causally important to the creation of meritorious research. It’s really telling in this respect that they zoom right past any attempt to demonstrate that meritorious individuals are necessary for meritorious outcomes. The history of science, since they’re so fond of it, suggests otherwise in the sense that many individuals who were not given meritocratic rewards for their unmistakably upper-right-quadrant research were nevertheless capable of producing such research and were highly motivated to do so. Many scientists who died holding important honors were only given that recognition late in life, long after they had undertaken research for reasons other than the achievement of meritocratic status. Meritocratic rewards don’t seem to be either a necessary nor sufficient cause of scientific knowledge production—and have been just as associated with what the authors regard as bad science as good science. (Lysenko received plenty of rewards for his scientific work.)

If we enumerated all the scientists who have been named as high producers of upper-right-quadrant outcomes since 1900, how many of them were the products of highly competitive meritocratic systems of admission, training and employment? For much of the 20th Century, that wouldn’t be the case at all—scientific biographies considered comparatively would turn up plenty of individuals who wandered rather accidentally into science, and many who selected into an area of inquiry that turned out to be quite important not because they survived multiple rounds of brutal meritocratic evaluation but because their subject matter was considered relatively unimportant and thus they were free to tackle it. Those biographies would also turn up many upper-right-quadrant scientists who highly competitive meritocrats (or their elitist predecessors) attempted to keep out of science. There would also be some question of whether increasingly competitive meritocratic conditions in the late 20th Century produced more upper-right-quadrant outcomes—Peter Higgs, for example, has noted that the more competitive, more quantitatively measured world of physics research in the last two decades would likely have prevented him from making the contributions that he did had those conditions prevailed earlier in his career.

The authors also come up with some hypotheses that they don’t investigate at all. (How very unscientific!) For example, it is better, they suggest, to have trained one star student than mentoring no star students. Is it really? If a research scientist trains ten highly competent researchers who do not ever become a “star” but who participate steadily in significant research collaborations for three or four decades, how does that person stack up against someone who trains two stars but whose other students leave research science altogether after only a few years, or who go on to work as executives for industry but do not actively engage in research?

Moreover, as soon as they hold that merit is partly about the enumeration of work, including the training of graduate students, the question of what stardom really is becomes complex in ways the authors do not acknowledge. A research scientist who is regarded as the meritorious creator of upper-right-quadrant scientific knowledge is today usually a person who has executive authority over a funded laboratory, responsibility as a mentor to graduate and undergraduate students, and the ability to make and sustain collaborations with peer researchers. These are all profoundly social skills, or ought to be—but how are those evaluated? Just by measuring outcomes? How sure are we that there is not even better science possible, with more upper-right-quadrant outcomes, if the social character of research in the sciences is different? How sure are we, for that matter, that the individuals who claim credit for what is produced are in fact actually responsible for it? Not just science but many other institutional worlds are rife with people whose primary skill set is leveraging power and resources in order to take ownership of work that they largely did not undertake themselves. What’s the empirical evidence that science, now very much a large-scale collaborative enterprise, ought to be individuating meritocratic credit for research outcomes?

The only body of scholarship that contradicts their arguments that they treat with even some intellectual seriousness is the critique of meritocracy in work by scholars like Sandel and Markovitz, but it’s another place where they essentially go with the “dog ate my homework” excuse that there’s just too much to talk about, and here, it’s way worse. This is the heart of what they want to talk about—the importance of merit—and they essentially brandish Thomas Sowell at Sandel and Markovitz like they’re vampires and he’s garlic. Case closed, done enough—meritocracy may not be perfect, but it’s the best we can do, always room for adjustments around the edges. There is a huge literature out there that is empirically rich. Given where they want to go, most of this essay should have consisted of reckoning with it, except that it’s primarily by sociologists, economists and other social scientists and they’d have to work with that scholarship on its own terms. That’s essentially what the editors of one journal that rejected the essay were trying to tell them: you want to put merit at the center of this essay? Then take the debate over meritocracy with some intellectual seriousness and dig down into it as scientists ought to. (Footnote 147, for anybody still following along.)

The authors are not about to pause on the real and substantive debate about meritocracy because they want to get on to the perceived dangers of contemporary “politicizing” of science. Here they throw a wild jambalaya of stuff into the mix. For example, they regard interest in natural or folk medicine as an example of a sharp “politicizing” turn, citing a proposed “decolonization” of pharmacological curricula. If you follow the footnote in this case, you end up finding out that what they’re representing as a generalized menace to All Science Everywhere is the particular advocacy of particular research scientists in a single particular country, South Africa, and in particular, the research praxis of a single research scientist who has taken an active interest in looking at the possible and claimed medicinal properties of indigenous plants. If the authors of this paper were even remotely dedicated to all the claims they make about the universality of science and the scientific method, they’d be profoundly unthreatened by such a prospect. Are they saying that it’s not even worth testing the medicinal applications of those plants? Are they specifying that all scientists have to have the same internally felt and psychologically experienced motivations to decide on a course of research? Talk to an actual scientist, and you’ll find that the biographical character of their motivations is wildly diverse and in many cases palpably “unscientific” at its roots.

More sleight of hand here: somehow the advocacy of a set of South African researchers magically stands in for some proposed change to how pharmacology everywhere is taught. (They don’t call it “a proposed change”, they call it “the proposed change” as if this is a standard, pending, universal curricular project unfolding everywhere.) And the authors don’t even pause to ask whether how something is taught ends up being how science is researched and subsequently ends up being how outcomes are validated. The South African researchers who speak in the short profile that is footnote #38 in “In Defense of Merit” are significantly talking about problems of pedagogy and motivation, about how they reach their students and motivate them to do science. The “Defense of Merit” authors suggest that projects of “decolonizing pharmacopeia” contribute to a “public infatuation” with folk remedies and cite an article showing that folk and natural medicines are generally untested and that few government agencies responsible for authenticating the safety and efficacy of medicines have tested these kinds of remedies. True enough! But this is not some rough woke beast posing a sudden threat to previously neutral pharmaceutical research, it is a problem of long standing and has little or nothing to do with critical race theory and all the other trends that scare the authors. Folk medicines have been a big counterpoint to biomedicine for the last century and yet somehow science has survived that just fine. (One could also point out that contemporary governmental regulatory approaches, where they exist robustly, are at least partly a political outcome of past carelessly ambitious scientific collaborations with industry to disseminate and prescribe drugs that were insufficiently tested. Debatable claims that zinc helps with the common cold aren’t what led to IRB oversight.)

The distinctions the authors draw between “liberal epistemology” and “critical justice epistemology” later in the article are kind of a flashback to the carelessness and lack of intellectual curiosity and independence on exhibit in the first part. Honestly, Figure 3 isn’t just crude, it’s also strangely arbitrary in the sense that the bullet points are less opposites and more rather closely intertwined—or a demonstration of how little the authors embrace what they claim to be their own epistemological values. Are they pluralistic? Accountable? Talking about truth provisionally? Testing their theories objectively? Fuck no. Moreover: do scientists reject all theories that cannot be proven or disproven by reality? Also fuck no. There are branches of scientific thought whose theories cannot be meaningfully tested within the boundary conditions of the universe as we know it, in some cases can never be tested (ontologically! objectively) because of the character of the theory.

Having actually read critical race theory, I can attest that much of it absolutely claims to be using falsifiable evidence to talk about what is quite real. If you go to its roots in legal theory, in fact, the original point was that standard legal scholarship was the unreal, unfalsifiable body of thought that refused the legitimacy of other interpretations. E.g., what critical legal theorists pointed out in the beginning was that the law itself did not explain many outcomes of legal proceedings, that law offered a frame for explaining its own processes and outcomes that was an ideology, not an evidence-tested analysis—and that understanding law as the privileged rhetorical and institutional apparatus for conferring power on a racially-organized hierarchy was more explanatory of persistent, long-standing outcomes. U.S. law (rather like science in the imagination of these authors) presented itself (after the 13th and 14th Amendments) as race-blind and race-neutral, but what critical legal theorists observed is that this was in no way actually the case.

Critical race theorists extending that critique elsewhere followed much the same process. It’s not a monolithic approach, either. It’s possible to say “if liberal institutions could be changed, it’s possible they would achieve what liberalism claims about itself”; it’s also possible to say “there is no evidence that they can be changed, and considerable reason to think otherwise”. That leads to different political projects—you can be a critical legal theorist who thinks there is some version of “law” that is possible and desirable or one who thinks there is no version of law or liberalism that is possible and desirable. Welcome to “intellectual diversity to maximize the chances of finding the truth”, guys. That’s how it works.

I have three suggestions for the authors of this essay. It’s plain that they’re not going to actually read the vast majority of the work they’re setting themselves against. The weakness of footnote 8 notwithstanding, it is a lot to tackle.

So suggestion #1: don’t write a sprawling manifesto if you don’t have the background knowledge necessary (and bandwidth in terms of length and labor time) to make a credible go of it: write tightly against just one essay or book. Spend the time, dig in, be responsible, be focused. The 2022 Science on “The Missing Physicists”, for example: what happens if they just engage that issue and that issue alone and read it closely, stick to its specific claims? Especially stick to the tough claims, not the easy ones.

Suggestion #2: Worried about bad administrative implementations of DEI policies, etc. in research institutions? Stick to those. There’s some salvageable objections between pp. 15-18, floating randomly among the wreckage of the whole essay. Don’t write Baby’s First Attack on Postmodernism. Moreover, if you want to think empirically about effectiveness in mobilizing coalitions to achieve a goal, don’t strap yourself to a giant epistemological bomb and run around the room screaming at everybody. Meritocratic scientists are supposed to be good at sustaining collaborations, remember?

Suggestion #3: Pick a genuinely tough case of a possible example of the intertwining of racism and science that rests on a robust bed of actual empirical evidence to reason back from in order to enunciate some different interpretation than the prevailing one. E.g., do the work of scientists. I’ll mention just one of the many examples that a piece that has the ambitions of this essay ought to have grappled with. The evidence that Black patients in the U.S. health care system have worse outcomes than white patients even when socioeconomic class is considered is extremely robust. That’s not in the past, it’s right now. A wealthy Black woman with a college education on average has worse outcomes from medical care than a lower-income white woman with no college education. Reason back from that to the idea that science and race are not entangled and that science has previously been driven primarily by the pursuit of objectively superior outcomes and the meritocratic recruitment of the best researchers. You could ask: is this a problem with application of therapies that should be race-neutral in their outcomes? E.g., throw doctors, nurses, hospital personnel under the bus. You could ask: is this a problem with the patients, e.g., do they differentially fail to follow instructions or delay seeking medical care? (You would then have to investigate why there might be a racial disparity in trusting medical expertise, which might lead you back to systemic racism. Remember! Science is objective.) Or you might have to ask, “well, is it possible that the therapeutic and pharmaceutical approaches derived from scientific research encode some kind of racial bias? Say, in the populations chosen to test therapies, or in the normative assumptions made in designing therapies about what an ‘average person’ is like?”

I’m just going to say that if the authors tackled #3 in the manner they regard as scientifically normal, they might get some more insight into what they’re attacking.

I’d also say that I don’t think that’s their goal.

Image credit: "fate, luck or Sleight of hand" by g_cowan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.