Academia: You've Got AI. Is It Terminal?

Thursday's Child Sees A Lot of Threats on the Board

Welcome to 2025! I wish I could say that I look forward to the year ahead, but I don’t.

My worries are many, but one of the most prepossessing concerns I have, perhaps outweighing the dark political clouds on the horizon, are the consequences of the unconstrained, unmediated, unconsidered release of generative AI tools and components into our informational and expressive environment. Whatever happens to our governments and institutions in the episodic to-and-fro of the next decade may turn out to be less consequential by far than the conjuncture of our informational and cultural infrastructures with generative AI.

I’ve been open to the new possibilities of information technology my entire life, even when those possibilities were entangled with undesirable or unintended consequences. I feel the same about generative AI in some forms and in some use cases. But to a substantial degree, those uses are not driving AI development and they’re certainly not driving the way AI is being incorporated without foresight, intention or controls into virtually everything we do, say and think. That incorporation may end up being absolutely lethal to the basic foundations of modernity, without bridging to something better.

While many claims being made for generative AI by the major profit-seekers involved in its development and implementation are hype-ridden nonsense at best and malevolent lies at worst, there’s a real and meaningful innovation at the heart of the matter. I don’t think some of the corporations and business leaders at play in this sphere really understand the implications of what they’re doing, and like many people in the history of information technology, they are less driven by selling a valuable service or product to willing consumers and more about being sorcerer’s apprentices casting spells they don’t understand with nothing like a conventional business plan to guide them on their way.

I am not so worried by the issues that preoccupy many teachers at the moment, namely a wave of AI-enabled cheating that is threatening to overwhelm much existing pedagogy. Here at least generative AI is not so much a major rupture towards a completely new reality and more an acceleration and intensification of long-standing problems. In the case of writing as a tool of assessment, the problem lies in the scale and structure of institutional curricula and in the kinds of assignments that many teachers in both K-12 and higher education have relied upon for decades. The use of writing as a proof that a student did the reading has always been a baleful mistake. The idea that a large quantity of writing would by itself secure mastery of writing expression equally so. At the university level, combine that with introductory courses that have hundreds of students listening to lectures and then meeting with teaching assistants and you have a recipe that has always encouraged cheating, that has always been bedeviled by forms of indetectable dishonesty. You are never going to notice in that sort of class if a rich kid hires someone to write bespoke essays on their behalf, because the writing you’re assigning is already a kind of fetishized substitution to begin with, an assumption that labor is a reasonable proxy for understanding.

That assumption has driven what Jenny Anderson and Rebecca Winthrop accurately depict as a withering loss of autonomy and agency in the American education system. No wonder students expect to be rewarded for effort rather than outcomes (an old expectation that Adam Grant rather bafflingly identifies as a new problem), because a fair amount of what we ask them to do in courses is to produce pounds of useless, discard-ready work on the grounds that this labor cumulatively locks in “skills” which can then be tasked to thinking creatively, expressively or meaningfully about difficult problems. Many of us have long assumed that this just happens somehow—we use metaphors of scaffolds and ladders and pyramids that are focused on a distant horizon of arrival, a promise that at some point your beanstalk will be in the clouds and you’ll be able to go explore the giant’s castle as Clever Jack, ready for anything. That many climbers fall off and go splat seems less a problem and more an intention for the faculty who build the beanstalks, if less so for the people who have to clean the bloodied grounds below. The model has always invited students to buy jetpacks, always preloaded a sort of cynicism about whether or how the work of education actually inflects into the credentials it authenticates and thus the labor markets it gatekeeps.

If generative AI breaks this model for good, well, so be it. It’s so baked into the economies of scale that most of higher education globally relies upon that I’m not sure what happens after that rupture, though I am sure that at more intimate scales, there are ways to counter the use of generative AI as a shortcut and to make all the work that you ask of students be challenging, expressive and personally tailored, to develop the autonomy that Anderson and Winthrop so correctly identify as crucial to teaching that really develops both skills and purpose in students.

The problem is that if we can make that correction to our K-12 and university education, we might cultivate the personhood and talent of free and imaginative individuals just in time for them to inherit a wasteland where those capacities have no value or avenue.

What is generative AI good for? What could it be good for? There are two primary use cases where I welcome its innovative and genuinely transformative possibilities.

The first is as a prosthetic extension of human creativity and agency at the boundaries of our existing labor economies and scales of operation. To give an early example, the use of Weta Digital’s MASSIVE software package in films like The Two Towers solved a problem in visual representation that couldn’t be solved simply by hiring more people, spending more money, or investing more time, not in a practical way. You can’t individually animate ten thousand orcs in an on-screen battle, any more than you can have every single person in the army of Rohan in Return of the King be an actual horse-riding person in full costume—and yet there’s a value to seeming to have that many people, that many creatures, at that vast a scale of visualization.

I am very willing to credit that there are a great many scientific, intellectual and cultural frontiers where that kind of extension of capacity now beckons to us and where, if generative AI were kept on a proper leash, the results would be both good and excitingly unexpected. And of course some of the unexpected outcomes would form a complicated feedback loop with our existing minds and emotions, our practices and preferences, in much the same way that the massification of print culture in two key stages (first after moveable type, second with industrial printing) not only increased the amount of reading and writing happening but changed how we thought about reading, writing, textuality and created economic value in writing and culture that hadn’t previously existed.

It may also be that there are labor economies here that are not just tasks too complex and massive for direct human management but also desires too ordinary and distributed to be satisfied by human labor, even with a universal social media infrastructure. There are millions of artists, but the millions of writers who might want a bespoke illustration to accompany their writing can’t match or afford bespoke artistic work. We’ve never solved the problem of paying for massified creative labor or of matching buyers to sellers and maybe we can’t without some form of generative AI involved as a bridging device.

Second, I think there are proper ways to use generative AI as a kind of muse, as a kind of tool for thinking strange thoughts, of imaginative estrangement from our first instincts as writers and creators, and for probing the collective unconscious, the corpus of all that has been said and thought, drawn and animated, solved and programmed. It is in this sense simply a massified, distributed and empowered version of experiments like Oulipo or a technological implementation of hitherto philosophical or theoretical conceits like Jungian analysis.

So then, where’s the fire? What’s the crisis? Where is generative AI potentially going to lay waste to the world we live in?

The problem is that it is not being used as a prosthesis to work beyond the frontiers of human capacity. It is being deployed in service to an anti-human ideology by a small class of oligarchs who loathe mass society, who hate democracy, who fear constraint. It is not being used to go where we cannot go, but in hope of replacing people in almost everything, to make a manorial society where a new feudal lord would hold court with a small group of loyal humans bound to his service while most of his needs and wants were satisfied by AI-controlled stewards, robots and simulations. That generative AI cannot do such a thing no matter how it is improved is not the point: it is what they are dreaming about doing with it, and are content if much gets wrecked along the way to discovering that they in fact live in a society and always will. These are people who have a half-assed belief in the Singularity without having really absorbed the point of the idea at all. They do not dream of being downloaded into a Moravec bush robot or being part of a post-scarcity transhumanity oozing across the stars one self-assembling machine at a time. They believe in ridding the universe of anyone who could say no to them, in order to stay just as they are. If they dream of immortality, it is the immortality of their present bodies, their present power, their present wealth.

For the rest of us, the indiscriminate vomiting of generative AI into everything we read and view, every tool we use, every device in our homes, every technological infrastructure we operate or own, means at best an unproductive estrangement, a new mediating layer that no one, expert or otherwise, can really understand or control. A kind of techno-tinnitus, a buzzing hum of interference or diffusion. When things break, when things don’t quite do what we want them to do, when we don’t get what we’re owed from what we’ve created or done, there won’t be anything to do about it. When we’re described, evaluated, measured, assessed in all the ways that are already balefully mindless when they’re done by actual human beings that we actually can see, we’ll suddenly become even less recognizable, even less true to our realities, and there won’t be anything to be done about it. You’ll complain about the AI processes in the black box to another black box AI and there will be no one anywhere who actually knows why it gave the results that it did, no expert Delphic oracle who can take it apart and get it back on track.

At worst, it means that everything that is translocal to our material surrounds will be untrustworthy and unknowable. Not even an interesting fiction, just a kind of informational drift, a noise so pervasive that the entirety of the signal gets lost. It’s already happening to the fabulous, almost-unbelievable informational infrastructure that humanity built from the late 19th Century into the beginning of the early 21st Century. For a short, amazing time we built knowledge that accumulated from the researches and experiences of thousands, then hundreds of thousands, then millions of people. We built more and more supple tools for accessing and indexing and cataloguing what we knew and we did things with it. It became possible to be confident that you knew meaningfully true things about places you’d never seen, people you’d never met, histories you’d had no part of.

Generative AI is being used so heedlessly, so much like a silicon equivalent of the Human Centipede, gulping down its own shit as it hungrily demands more and more and more text for its training models, that it is going to end up spewing informational diarrhea forever all over the entire infrastructure of knowledge production. It is going to pollute all forms of many-to-many communication, all forms of mass media. When we hit that point, it will be impossible to cleanse it all out again. Everything we know will become a Superfund toxic waste site, full of forever hallucinations and distortions.

You can see it already in library catalogues, where the relevance hierarchies are drifting because no human being is calibrating or correcting them, where no bibliographic control of any kind is being used. You can see it in places like Reddit, where increasingly every subreddit is getting pounded by repetitive bot-provoked threads that aim to relitigate long-arbitrated conversations because (at least for now) the text-making humans who are still reading and posting still reliably make more text when they’re prompted which can then be freshly scraped for more training data. You can see it in the mad rush to buy every bit of text, every recording of speech, everything every drawn, to keep the AI fed. You can see what’s coming: we’re a year or two away from it. Everything deepfaked, every fact a possible hallucination. Reporters are already accepting at face value that Woodrow Wilson pardoned Hunter deButts, his brother-in-law. It’s all very funny until we get to the point where to know otherwise would take getting a hold of original printed material in archives to show that Wilson never did such a thing. And then tragic when it turns out that you can’t tell anyone what the original material says because the AI-mediated digital communication spaces relentlessly correct you and insist that Hunter deButts was in fact pardoned. When the print materials are inaccessible because who needs human archivists anyway. When the print materials are destroyed because they take up too much space and are too costly to preserve.

Why? What’s it for? At this point, none of the people doing the training even care what it’s for. Moloch is hungry. Moloch needs not only all the text, all the art, all the songs, all the code, it needs all the electricity. We’re probably only a few years away from mandatory brown-outs in ordinary homes because the AI needs the power.

You could say that here too we have dug our own graves. If the 500-person introductory course that has a bunch of lunchmeat writing assignments that almost demand to be cheated on is just asking for ChatGPT to blow it up, then what of an entire economy that is built on compensating people to write deliberately empty, inexpressive, content-absent words: messages from CEOs and organizational presidents to their workers, speeches from politicians that are mirrors of polls and focus groups rather than expressive and meaningful statements of individual thought, and endless tons of journal articles that were written to keep academic jobs rather than advance human knowledge in meaningful ways? We long ago became the million monkeys on typewriters. Who cares in some sense if the busy executive has GPT to write something procedural and empty rather than a poorly-paid executive assistant? Who cares if the thought leader now has Notebook LM to summarize all the materials they don’t have the time to read personally rather than an eager intern?

The problem isn’t just that this vast understory of people doing work is going to get cleaned out. Maybe that won’t even happen exactly: you’ll just rehire (at lower compensation) the eager intern to supervise Notebook LM and to further edit or prepare its reports for consumption by the thought leader. The problem isn’t just the informational drift that will take us from some kind of fact-based knowledge into hallucinations standing on the shoulders of delusions. It’s more epistemologically and psychologically profound than that. We will not be authors or authorities. We will not be agents of our own lives, or in control of anything beyond the immediate materiality of our existence. We will not be bigger than we are, ever. It’s not going to stop with the intern and the executive assistant. The thought leader goes next. It’s not going to stop with animating the orc armies: the next step is going to be telling an LLM to make a whole movie of Lord of the Rings. And then to make a fantasy novel itself—again, we already paved the way, since what is Eragon or The Sword of Shannara but a premonition of GPT-as-author? At which point there will be nothing new coming into the digestive tract. Imagine a human mouth eating AI feces forever.

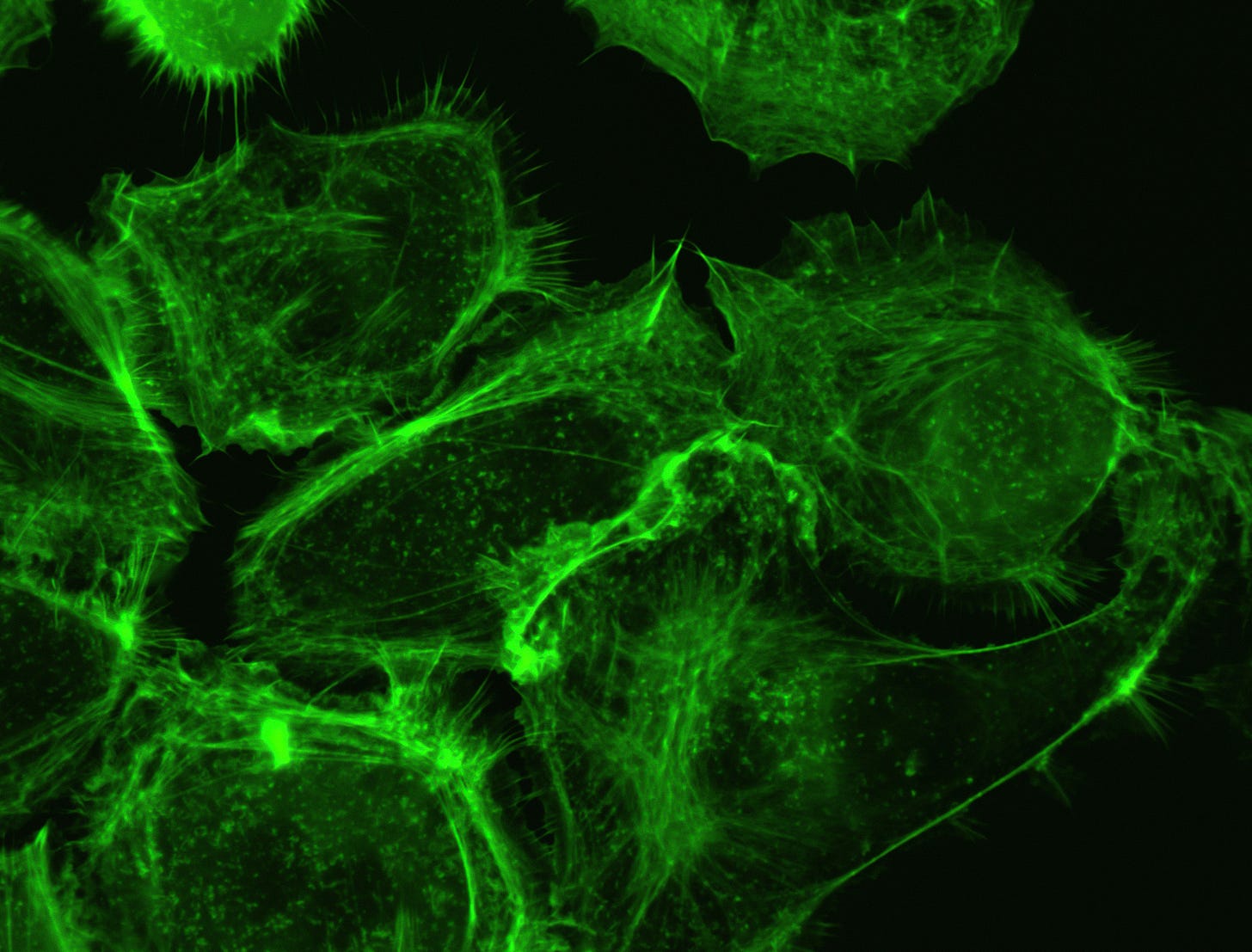

We’re not talking about the Forbin Project, not the kind of computers that Captain Kirk likes to blow up. These are not general AIs, not superintelligences, not rulers who run the world with remorseless efficiency and an eye to self-preservation. These are infrastructures we’re talking about. But that’s what cancer is too: a cellular infrastructure that destroys its host without intention or design, without malice or sapience, doing what cells do but doing it wrong. Doing it without the controls that destroy pathogens and replace broken or dead cells.

Maybe we’ve been growing ill this way for a long time, living at scales that rob us of the hope of control, losing general perspective and human connection. But generative AI is a vast accelerant of that illness. It will make it impossible for us to restore agency, renovate meaning, bring back a sense of connection. If the oligarchs want to live in manorial splendor, served by machines and blissfully untroubled by the human bumpkins who have the temerity to say no to them from time to time, then the rest of us are likely in a world of uncontrolled generative AI to end up in tiny fief-like prisons, where the only information we can trust is visible to our eyes, heard by our ears, helplessly confined to locality. To be diminished in ways we can scarcely imagine now. We are facing not the Singularity but a kind of brown-dwarf burnout of the burning sun of modernity.

Right now, I see no one prepared to put a leash on generative AI, to harness it specifically to the uses and possibilities for which it is best suited. Everything—yes, including all the cheating—is reinforcing generative AI’s oncological character, everything is acting to push it into the ordinary infrastructures of talk, of representation, of knowledge-making, of indexicality and discovery. Every small, fractional surrender of agency to some unconsidered, undesigned, unintended injection of AI into a tool where it’s not needed, a circuit where it interrupts, a calibration that it throws off, is making it what we should fear rather than the transformation we should welcome.

Image credit: Photo by National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

does the existence of a bunch of vapid mindless writing that has existed especially in the last 100 years (L Ron Hubbard's fiction in pulp magazines in the 30s comes to mind) just show AI will be more of the same? I feel like the real thing threatening the usefullness and existence of expertise and good writing and creative thinking isnt AI but economic conditions and social structures. in terms of not actually knowing local facts, I feel like the decline in local news coverage which has already happened has done more damage than AI ever will, but maybe im optimistic

And this is part of it, our knowledge repositories handed over to the vagaries of internet whims: "When the print materials are inaccessible because who needs human archivists anyway. When the print materials are destroyed because they take up too much space and are too costly to preserve. "