From the premiere of Blazing Saddles in 1974 and for years after, it was common to claim that the Mel Brooks film signified the end of the Western as a genre.

Was that a cause or effect? You could point out that by the time the film appeared, the genre was already defined more by its appropriation in cinematic subcultures like blaxploitation and by various revisionist, deconstructionist or anti-Western films. Little Big Man premiered in 1970, and for the rest of the decade, the most notable big-budget Hollywood-produced Westerns were weird genre variants. By 1980, the Western was just a precursor template for films in other settings, like Outland, and while the genre has stayed alive at the margins of global popular culture, Blazing Saddles is as good a marker of its end of predominance as any.

The view that Blazing Saddles was the cause of that end rests on the idea that when you can make fun of a genre for its tropes and conventional plotlines, you’ve called attention to its irrelevance. It’s a sort of Brechtian act of distancing, pulling the audience out of the genre. (As opposed, say, to making a funny Western that is partly funny because of how it plays with the genre’s conventions, or an anti-Western that nevertheless locates itself inside the genre.)

I don’t think the argument really works, partly because Blazing Saddles holds up better than you’d think, and not because of the relevancy of its transgressive working with racial stereotypes or its profanity or the campfire farting scene. (There are two other Brooksian preoccupations that really are jarring now: one is his predilection for rape jokes, the other is his fixation on gay effeminancy as intrinsically funny.) The film still plays well because in the end the film actually has some fondness for the Western and because weirdly enough the characters and story are actually rather satisfying despite being self-aware parodies of genre archetypes. Blazing Saddles has not come to bury its source genre, and you can’t help but to root for Sheriff Bart, the Waco Kid and the people of Rockridge even when the showdown with Hedley Lamarr takes place outside of Grauman’s Chinese Theater and the ride off into the sunset is in a limo. Maybe Blazing Saddles was a symptom of the genre’s morbidity but it wasn’t the underlying illness.

In the same sense, is Deadpool and Wolverine a sign that the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the superhero movie are at the end of their dominant position in global popular culture?

Warning: scattered spoilers to follow. There are a few actual amusing cameos and such in the film if you are a comics nerd, which I am, and I recommend not knowing about them in advance.

The film itself is acutely aware that it may be read as a sign of trouble even as it is gleefully aware that it will also save the company’s bottom line. It encourages that reading on multiple levels. (Deadpool boasts that he’s “Marvel Jesus” and it is one of the most metafictional things he says in a film bursting with metafiction.) It starts by gleefully desecrating the one superhero film that even Very Serious People have allowed themselves to like. Its central story, such as it is, involves a pompous British-accented villain wanting to speed up the decay of older superhero movies made by Fox, partly (he hopes) to please his bosses (who are implied in some sense to be Kevin Feige and Disney) who he supposes are eager to make use of their regained corporate property without tedious referentiality to what came before. Much of the action takes place in the Void, previously seen in Loki, where irrelevant intellectual property is sent to die.

On the other hand, it ends on a note that combines regret and naughtiness: Wolverine and Deadpool do something together that should mean their complete and final annihilation, in a heroic sacrifice that the film briefly toys with wanting us to feel something about. Then the characters discover (to their own surprise) that they are unkillable, as long as their owners want them back. As Deadpool jokes earlier in the film, Hugh Jackman is going to be forced to suit up as Wolverine for the rest of his life. Just as Robert Downey Jr. is going to be suiting up as a man in armor once again, apparently.

If I hopped in a time machine and visited my twelve-year old self, who was at that time in sixth grade occasionally walking about 3 miles roundtrip from home to a nearby drug store that had comic books on a rack display so that he could buy some superhero comics and sneak them home in defiance of his mother’s edict that it was time to grow up and stop reading comics, and tell my younger self that superhero movies and TV shows would be a major and successful genre of American popular culture for most of the first third of the 21st Century, I would have been regarded by myself as a complete liar. It would have been easier for 12-year old me to believe that Earth had joined the Galactic Federation by 2024 and I was the commander of my own starship.

Not more gratifying, mind you. Not only was I defying a maternal edict in smuggling comics home, I was painfully aware that I was courting the contempt of the entire adult world and adding one more reason to a long list of reasons for getting the shit beat out of me by other kids. So to hear that it was completely acceptable to like comic books in mainstream culture would have been a wonder, if hard to believe. (Though I can’t say that I would be any more eager to sit down with most of my colleagues and talk about my detailed knowledge of the form than I might have been thirty years ago.)

With this in mind, the even more incredible news I would deliver to my younger self is that I’m kind of sick of superhero films. Deadpool and Wolverine pushed me to feel that way.

This feeling of “superhero fatigue” is something that the media, especially film critics, have more or less been trying to plant in the collective mind of the world since the premiere of Iron Man. That project in turn was just a more specific iteration of something that middlebrow film critics have been lighting candles and praying to household gods for since 1977: they’ve wanted the summer blockbuster, the Christmas box office smash, to just go away forever. For decades, that disappearance was the dream of people who actually lived through and thus pined for the weird, wonderful moment in American film when very serious, well-made and beautifully acted films also made a big profit, from the late 1960s through to the mid-1970s. As new generations of cineastes came forth, the hope for a return to or reinvention of that era remained. (The Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences has remained particularly captive to this dream, even though it also has to pretend to love its gloriously profitable and aesthetically unworthy children like Avengers: Endgame.)

I want to say that my own form of fatigue with the genre is more complicated than a simple kid-in-a-candy-store sensation, of getting tired of gorging myself on a favored genre’s numerous treats. No sir, what I have is the sophisticated fatigue of a true fan. I am tired of the standard-brand candy in the store, but I’ve got an idea of possible goodies yet to be made.

Yes, I’ve had my fill of adaptations of the classic pleasures of superhero storylines from the past, from watching characters that even I expected to be completely stupid and goofy actually be rethought and improved for a film or TV adaptation. (I will say that I accurately predicted that nothing good could come of the Eternals because there’s nothing there to actually adapt.)

The problem is that the MCU has developed the same problem as the superhero comics that its owning corporation and various rivals have produced since the 1960s. I am actually surprised at how fast Marvel Studios succumbed to this sharp limitation on the storytelling possibilities of the genre. I’m surprised because I think it’s an unnecessary limitation. Because in fact the popularity of the MCU films was due to seeming to escape that limitation.

A sign but not the cause of this entrapment is the multiverse, and Deadpool in his classic wall-breaking, pastiche-referencing style actually says so in the film. “The Multiverse”, he says to the camera and to Marvel’s executives, hasn’t worked out so well. It is, he says, “miss after miss”. This is a kind of multi-layered referencing of fan discussions—it’s almost as if Deadpool is posting a thread on r/comics—that is itself getting pretty tired in mainstream pop culture, as if quoting fans is both complimenting them and trying to make them look ridiculous in the same moment.

The Multiverse is not the source of the problem, though. Deadpool rather bafflingly says that The Wizard of Oz got the idea of a multiverse right, which I can’t make heads or tails of. A portal story isn’t a multiversal story or a metafiction, necessarily. The Narnia books would be closer in that we eventually learn that God has created many universes—the Wood Between the Worlds is full of portals, and the children in the stories are not the only ones who have passed between universes.

In comic books, the MCU’s Void is really just a refurbishing of Grant Morrison’s arc on Animal Man, where the titular character eventually finds his way into a dimension where old characters wait to see if anyone will eventually reinvent them for contemporary readers, only to go from there to a meeting with Grant Morrison himself. Morrison points out to Animal Man that he is not Animal Man’s God or even a demiurge to his character, that someone else created Animal Man, and that a corporation owns the character and does as it pleases with him.

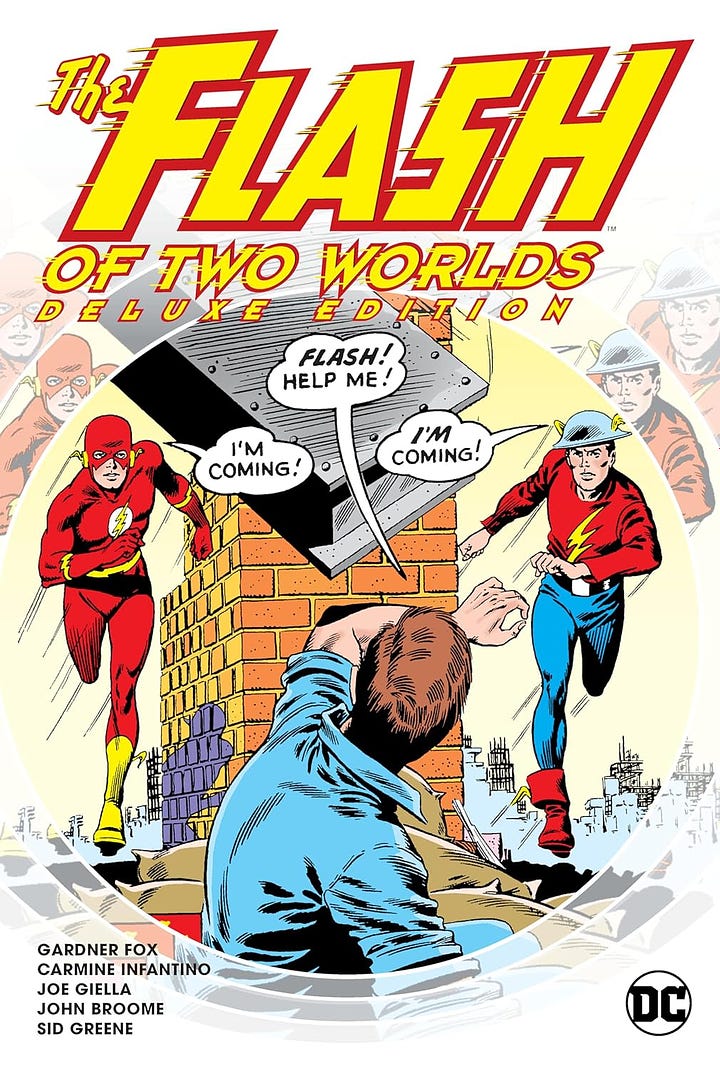

Morrison has insistently worked this theme ever since, and has done a lot to show that its roots precede him—the seminal work he keeps returning to is 1961’s “Flash of Two Worlds”, where the Silver Age Flash (Barry Allen) discovers that a comic-book character in Barry’s world, the Golden Age Flash (Jay Garrick), is a “real” superhero in a parallel Earth, whereupon the two Flashes meet each other. Until Morrison, the oddity is that comics readers simply accepted in a rather straightforward way what is actually a metafictionally fascinating kind of recursion—how can it be that there is a comic-book in a world of superheroes that is also accurately referencing the narrative events of a parallel world of superheroes? How is something lived in one universe becoming a story in another?

In a broader sense—as Morrison and Alan Moore and others of the more sophisticated breed of comic-book writers are plainly aware—this kind of metafictionality is a very deep property of global fiction and myth. In an older era of literary criticism, we would talk of allusion as if it were a fundamentally different thing. But Western literature since 1500 is full of referencing and reimaginings of Biblical narratives, Greco-Roman mythology, iconic historical events and personalities, folkloric stories and fairy tales. In the Marvel comics of the 1960s and 1970s, the editors were very prone to pop up and tell readers about the issue number that the characters were referencing in their current adventure, sometimes involving characters in other titles who were not even present. You could frankly have used such an editor in 1610 while trying to read Spencer’s The Faerie Queen or to have a little editorial box tying a specific bit in Shakespeare’s plays to Holinshed’s Chronicles. Much of Western literature is a giant “universe” of shared referents, of characters crossing over from an older text into a newer one with a new name and in a new situation but often repeating their old stories.

The difference in modern popular fiction generally and in comic-books specifically is the density and rapidity of the referencing. Writers and artists dig faster, deeper and more capaciously into the deep veins of the cultural past and especially for people who know the references it sometimes gets exhausting. Hey, look, O Brother Where Art Thou? is The Odyssey! Clueless is Emma! and so on. It gets harder and harder to be clever in these retellings, repurposings, borrowings, meta-commentaries and allusions even as the raw size of the culture grows well beyond what anyone can consume or be aware of.

This is where we get back to the problem of multiversality in superhero comic-books. Multiversality in this genre has become a way to balance two imperatives that are ultimately incommensurable. The first is to steadily maintain the value of intellectual property, while the second is to keep people reading and buying a never-ending set of serial stories that take place in the same fictional setting.

The first imperative was relatively late in developing. Sure, individual creators in the 19th and 20th Century have discovered (sometimes to their dismay) that the maintenance of popular characters and settings was a lifelong source of income. But big media corporations that ended up owning the rights to many such characters and works took a long time to recognize what they were sitting on, in relative terms. At least some of that slowness was technical: writing Tarzan or Sherlock Holmes or Superman was in relative terms easy. Making films or TV shows that looked the way readers imagined those characters was hard and expensive, as anyone who watched George Reeves leap awkwardly out of windows can attest. Creating more written work that didn’t meet the standards that audiences has developed was also hard, though the Oz books and many other similar series kept going for some time after their creators’ death. But all of that pales next to the constant recursive prowling through intellectual property inventories of the last forty years, which is partly a result of having discovered how to adapt a lot of the work in those inventories into more profitable forms and markets.

The second is an old problem, and not unique to superhero comics. As my wife is fond of observing, soap operas and telenovelas have the same issue as the comics. How do you keep telling stories about the same characters in the same place where things are also supposed to happen that change the place and change the characters? Marvel’s stock in trade from the outset of its cultural and commercial success was particularly premised on the connections between different characters and their stories, on the maintenance of its “continuity”.

In all serial storytelling, the problem is that eventually too many improbably bad or important things have happened to the same people without them showing any of the consequences we would expect. At some point, this issue became a more acute problem for superhero comics than soap operas. For two reasons: the first because actors and actresses age on soaps and inevitably pull the story along that way even if the writers and producers would rather not progress it, and second, because soaps lost their audiences. Superhero comic universes started to face two related problems. First, the character biographies started to become improbably long. Reed Richards and Ben Grimm in their initial stories had fought in World War II, and the adventure that gave them powers was a result of a desperate attempt to win the space race. If you’re using the same characters in 2000, you have to move up their history, but that dislodges continuity. But also, they’ve all experienced the same story cycles again and again—they should be unruffled about a companion dying because they almost always come back to life. The universe itself almost ends nearly every Tuesday. They’ve been torn apart, tortured, betrayed, beaten so many times. Gotten new powers, lost all powers. Been mind-controlled, had an evil twin. But there they are, doing the same old same old, seemingly unaffected.

The multiverse became the answer to both problems: guarding intellectual property and telling stories where things actually happened. If you created intellectual property and then stopped using it for a while, never fear! It’s still there, in a parallel universe. Every once in a while you do a story in that universe, or let your regular characters visit it via time-travel or a portal. The lawyers are happy: the claim remains staked, even on characters nobody wants to use right now. And you can do anything to characters in parallel realities, time-travel alternatives. The Blob can kill and eat the Wasp. All the X-Men can die at the hands of the Sentinels. Spider-Man can have a daughter who becomes Spider-Girl. You don’t have to tell a linear story that unspools and eventually all your characters retire, die or break under the burdens you’ve placed on them. You can always undo everything, always reset everything.

Which brings me back to Deadpool and Wolverine. Deadpool, who is comic-book editor, comic-book fan, and comic-book character in one, knows that a lot of fans don’t like the MCU’s multiverse stories. But I’m not sure if he knows, in any of those personas, exactly what the issue is.

The issue is that the MCU was on the verge of being a story where things happen and they stay that way. Marvel Studios told a story to the audience about having a plan for three phases of films. That was plainly something of a post-facto bit of marketing, but by the time the curtain came down on Phase 3, it had become a reality. Avengers: Endgame actually moved the story forward. Things happened! Characters changed! A terrible event was undone but people remembered that it had happened, and remembered the trauma and loss of it. Thor fell into depression. Hawkeye started killing criminals. Captain America helped save the universe and then decided to finally chase his own happiness. Iron Man died.

And the next couple of steps seemed to commit to keeping the story moving. New characters stepped up, older characters accepted the legacy passed to them. The universe healed a bit from trauma, but didn’t forget it. This was popular. It is what the audience wanted.

It’s definitely what I wanted: an adaptation of a superhero universe that would keep the story moving, that would age with actors, allow the status quo to change. Since films and TV shows are sufficiently expensive that you can’t just churn them out like comic-books, I figured there would be a material limit that would keep Marvel Studios from tripping over their own authorial feet.

But somewhere in there, the guardians of the intellectual property plainly got nervous. What do you mean there’s no Tony Stark? No Iron Man? That Captain America is now a Black guy played by Anthony Mackie? And the creative teams got nervous in the other way: wait, we have to tell a story that follows the last story? We can’t just do our own story in our own way?

The multiverse beckoned. Need Doctor Strange to learn a lesson about his limitations? Show him what he’s like in another universe, and show him what a bad universe is. Need to undo revealing Spider-Man’s identity but also to synchronize the MCU version of the character with his intellectual-property standard version? Cast a magic spell, but also show him other Spider-Men and have him learn the hard lesson about great power and great responsibility. Undo, redo. Move the trauma and transformation off into other realities. Need a Fox Wolverine who didn’t die protecting young mutants, or a Deadpool who isn’t stuck with some X-Men that you’re going to revise?

Studied comics nerds like me know where the narratological wind is blowing here. The MCU originally surprised us in all sorts of pleasant ways, not the least by committing to some of its stories and character moves. I don’t think we’re going to be surprised again in a good way.

Downey Jr.’s casting as “Doctor Doom” is a multiversal fake-out—he’s probably going to come over to the MCU via the Fantastic Four film. I’m nearly certain that the Fantastic Four film is going to feature the destruction of their universe, which will be a nostalgic revisitation of the Lee-Kirby era of Marvel storytelling. My best guess is that just as Tony Stark was Peter Parker’s mentor in the “main” MCU, Tony Stark will be Reed Richards’ college rival in the FF universe. That Doom is going to come over, beat the crap out of the MCU’s heroes, and then get shanked by the MCU’s version of Doom, which will be a fan favorite casting that gets everybody to cheer—and that version will probably say something like “you know, wearing armor—that’s a good idea—thanks for the suit”. Whereupon in the next film, the entire universe is going to get blown up and everybody’s going to get recast except for the actors who are so popular at that time (maybe about 2030 or so) that they get to keep playing their character going forward.

Only there won’t be any forward, because it’ll just be the same storytelling ouroborous ever onward, a capitalist-fueled dragon forever eating its own tail.

I wonder, though, if the dragon is going to hibernate. Perhaps Deadpool was an ominous prophet in that wall-breaking moment. Perhaps in succeeding commercially in this film, he will lure Marvel’s executives even deeper into the multiversal, where their ownership is never impinged upon by the risk of a story that dares to move forward. I think they’ll find that if there’s fatigue with superheroes, that’s the real reason. It’s not too many shows and movies, or the quality of the shows and movies. It’s that none of them really matter. Nothing ever actually happens. For a brief moment, I think some of the audience thought otherwise, and they liked that feeling, of a sprawling metafiction that had a beginning, middle and end, where characters died, changed, had feelings, made decisions.

At least that’s why I’m fatigued. I was superficially and momentarily entertained by Deadpool and Wolverine, but two days later and I’m already forgetting it—and feel no sense of desire to see it again. Because who cares, after all? There is nothing that’s going to happen that doesn’t unhappen. Not in that film, and I suspect not in anything the MCU puts up on the screen from here on. Whereas after Endgame I was actually engaged with the question: what happens next?

Maybe it is not parody that signifies the end of a dominant genre. It is when a genre, and its creators, lose a feeling for why it ever worked in the first place. When in some sense, it no longer matters. Maybe that’s why Blazing Saddles seemed to signify the end of the Western, because it was no longer laughing with the Western or even at the Western. It was just using the Western to tell a joke.

I lost interest in the MCU, despite seeing the earlier ones as they came out.

Part of what signaled the collapse for me was not Deadpool, but Taika Waititi's take on Thor. You can't parody *your own product* and expect fans to take it seriously. People want to see Thor beat up villains and save the world.

Instead they gave us "NOT ANOTHER SUPERHERO MOVIE".

If they want this to be a "universe" that keeps fans invested, they needed message discipline (clean up the completely disparate tone across the movies and - far too many - tv shows). Get your plot holes filled. And don't give your formula, ready-to-heat, movie model to some show-off director to turn into his auteur project (see also Zach Snyder).