Here comes another occasional Monday column type.

You don’t have to know the long-running British science-fiction show Doctor Who to make sense of this column, but it will doubtless help. In the show, a very human-looking alien from the planet Gallifrey travels around space and time in a machine that looks like a British police box. They go by the name of the Doctor, periodically “regenerating” into a new body (male or female, though it took a long time for the show to have a woman Doctor). The Doctor has a long-established interest in the affairs of the planet Earth and particularly seems to hang around the UK quite a bit. The Doctor invites or allows a select number of human beings to travel around with him as companions. The vast majority of them are contemporary British citizens, but the Doctor has also travelled with an Australian, an American, an 18th Century Scotsman, and several human-looking aliens from various eras, including the far future.

Since the show’s revival in 2005 after going on a long hiatus in 1990, the Doctor has typically had one female companion until the last few seasons, where she had three (two men, one woman). The companion characters have had much richer backstories and dramatic arcs than in classic Doctor Who but I’ve been a bit frustrated that a show that has all of time and space available to it sticks to modern British characters, mostly white with a few recent exceptions.

So this column will be my occasional attempt at nominating interesting individuals from the past that I think would fit the dramatic situation and format of the show. That means several things:

No really famous people. Trying to write famous, well-known historical individuals as interesting characters who have unpredictable dramatic arcs is fun in its own way in time-travel stories but it limits what writers can do with that character. The audience is too familiar with the person—they know how their story begins and ends, they have expectations of how they will act. Doctor Who, like other time-travel fictions, enjoys playing around with famous historical individuals—the Doctor has met Vincent Van Gogh, Agatha Christie, Charles Dickens, William Shakespeare, Rosa Parks, Elizabeth I, Madame du Pompadour, Winston Churchill, etc.—but those episodes tend to illustrate the point that there are only so many things that can happen to such a character before the willing suspension of belief breaks. (Usually the show takes a comic tone with these appearances, or centers on a known event in the life of the historic individual, but occasionally there’s a more serious and moving feel to such an episode, as in the case of Van Gogh’s appearance.)

People that we know enough about that they have genuine specificity as individuals. E.g., no generic “Aztec warriors” or “Igbo merchants”. This is a constraint that dramatically thins the field of possibilities, but this is where being a historian who favors microhistory as a genre of research steps to the fore. A real individual with specificity generates the story possibilities in the context of a show like Doctor Who. It’s much harder to create a fictional individual from most past societies who doesn’t immediately become a generic cliched Everyperson from that time and place. “Roman patrician”, “Portuguese sailor”, “Mongol warrior”, “Nahua priest”, etc.: to make that character into a specific individual who retains their historical reference takes a ton of research and specialized knowledge.

People who plausibly could have hopped on board the Tardis and returned at some point (often almost to the moment they left) changed by the experience without that change altering something fundamental in their life as we know it through historical evidence. But similarly, people who could plausibly hop on board the Tardis and never return without that being a significant change in history. (The Doctor does sometimes drop off a companion in a time and place other than the one they came from; far more unusually, a companion may die in the line of duty.)

Ok, so those are the ground rules. Here’s my first nomination: Edmond Modeste Lescarbault.

I came across Lescarbault while reading Thomas Levenson’s The Hunt for Vulcan. This sounds like I’m going for a cross-over between Doctor Who and Star Trek, but Vulcan in this case is a non-existent but hypothesized planet that some astronomers believed orbited the Sun closer than the planet Mercury.

Levenson talks about Lescarbault’s major claim to fame, which is that as an amateur astronomer, he claimed in 1859 to have observed the transit across the sun of a small planetary body inside the orbit of Mercury, which drew the approving attention of the French astronomer Urbain Le Verrier (famous for predicting the existence of Neptune). After Lescarbault’s observations were reported to the press by Le Verrier, the supposed planet was given the name Vulcan.

Here’s what Levenson has to say about Lescarbault:

Edmond Modeste Lescarbault was a humble, almost diffident man. He lived a small life, confined mostly to a modest compass between the Seine and the Loire rivers, about seventy miles west and a touch south of Paris. He had studied medicine, and in 1848 opened a practice in a little country town, Orgères-en-Beauce. He stayed put there for the next quarter of a century. He died in 1894, ninety years old, locally honored—the street where he kept his surgery is now named Rue du Dr. Lescarbault—and generally forgotten.

Levenson continues:

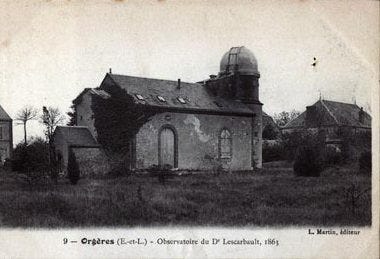

The country doctor had one great passion. As a boy, he had fallen in love with the night sky. Children grow up, of course, and most put away childish things. Not Lescarbault. Like many before and since, he discovered in astronomy the same consolation that would later comfort Albert Einstein: the contemplation of ‘this huge world, which exists independent of us,’ which, he wrote, serves as ‘a liberation’.

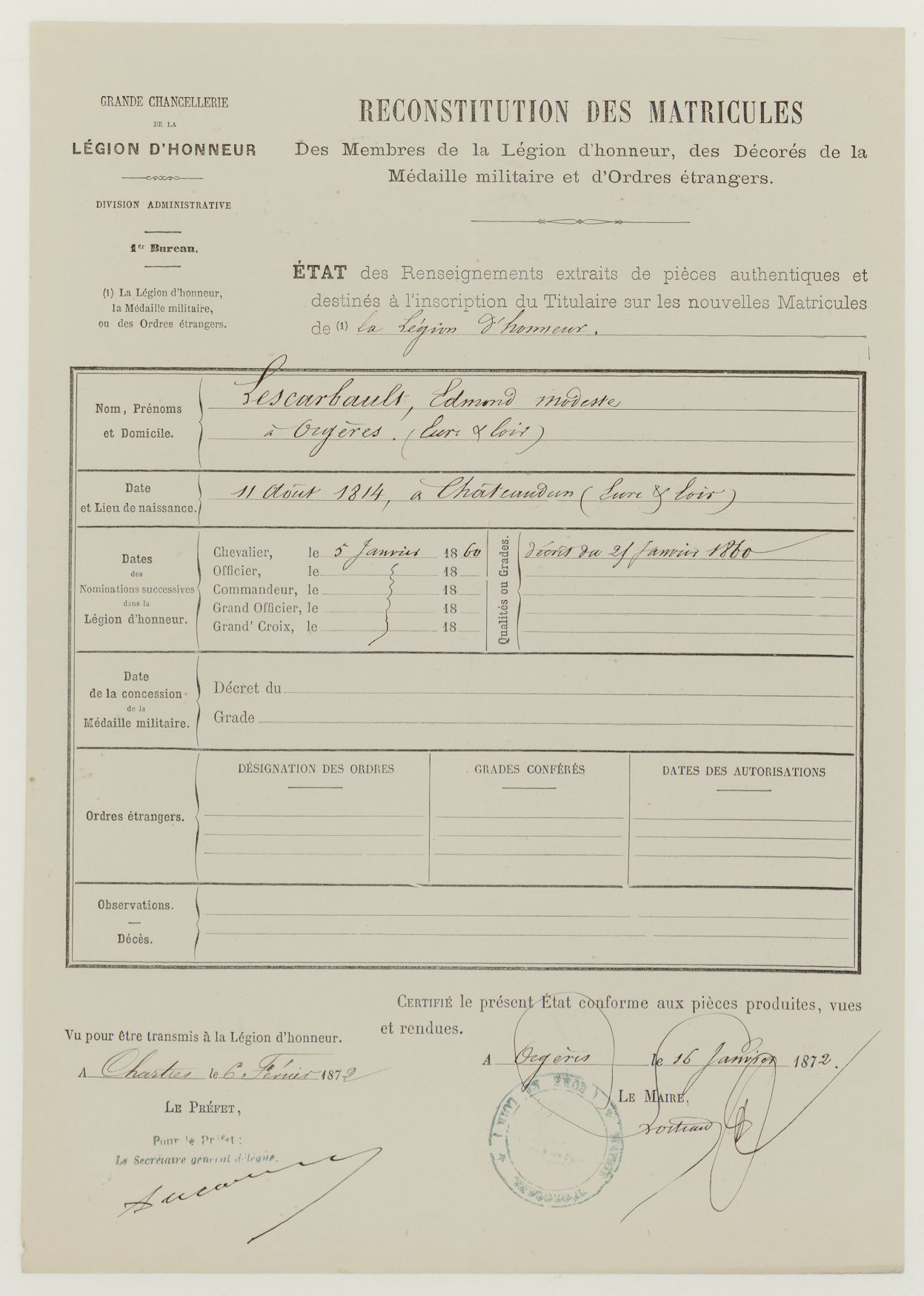

Lescarbault built a quite significant amateur observatory in a barn and decided to look for a small planet transiting the sun, which required him to acquire more instruments for his telescope. In 1859, he believed he’d seen the transit he was looking for and then waited nine months to write to Le Verrier. Le Verrier and a companion went shortly afterwards to visit Lescarbault and decided that his observations had been accurate. For his discovery, he received the Legion d’Honneur and that was pretty much the end of his brush with fame.

Reading about Lescarbault in a few short pages of Levenson’s history was what gave me the idea for this column because I could see the character so clearly as a Doctor Who companion. He’s a doctor, a modest man, he lived most of his career in a small French town south of Chartres and southwest of Paris. He had one major interest outside of his work that led to a brief moment of fame. But it’s that letter that Levenson quotes that really sells it for me. Imagine him writing that letter after he’s travelled through time and space for a while. It takes on a whole new meaning: the man fascinated by what he could see through a telescope in a barn has been to the stars. And yet he’s come home again, still humble (all the more so, now that he knows how vast and strange the universe really is) and still dedicated to his medical practice.

It’s possible that if I went off to France to do archival work on him, I might find out something about Lescarbault that complicates or upsets this picture. Once we’re in the nineteenth century in many parts of the world, individuals have enough traceable information around them that you can generally get a picture of their everyday lives beyond the one moment that they leave a more spectacular archival trail. But this is enough to go on for this purpose: a real life that would lend itself to this particular fictional purpose.

Date of Tardis Departure and Return: 1861. The glow from discovering Vulcan is fading. He’s still out there in his observatory in his town, still running his medical practice. And then suddenly his life takes a turn.

Story Role: He’s a man in his mid-50s. Doctor Who benefits a lot when there are some older characters in the Tardis, I think—that was the best part of some of the most recent seasons. He’s a medical doctor—that’s a handy skill to have along on an adventure. He’s fascinated by space and by science—that’s an endlessly productive story hook for this show. He’s humble, a respectable member of the mid-19th Century French bourgeoisie—that could make for some interesting relationships with more brash, modern and British characters. The 19th Century context is pretty well known to contemporary audiences, so there isn’t going to have to be a lot of exposition from the character explaining what he does and does not know.

Dramatic Arc: The character could be played either as someone struggling with a feeling of disappointment as the stars go from being distant, gauzily romantic mysteries to being quite concretely full of Daleks, Cybermen, etc. and science being something that just as frequently leads to death and destruction as it does to progress and revelation; or he could be someone who is endlessly awed by the new wonders he witnesses and who is a kind of “steady rock” for the rest of the Tardis crew—who provides some of the emotional guidance and explanation that the Doctor sometimes doesn’t. (He’d make a good foil to a more brusque, alien or mysterious Doctor, as well as to a more action-oriented and youthful Doctor.)

Yes, I would like to see this companion!