I will be resetting the sequence of regular entries in the year to come in order to go about something like normalcy in times that may be increasingly abnormal as the year 2025 progresses.

For the moment, I want to spend a few weeks thinking on specific histories that lay out the life span of an authoritarian or autocratic political system or movement: how it gained power and how and why it eventually lost it. I’m not going to be shy about drawing analogies, but I’m also going to stress the differences between then and now.

I can’t promise these will be encouraging, either. That is part of what we need to be thinking about now.

The South African state under the rule of the National Party and the system of apartheid began in 1948 and ended formally in 1993.

Over those long years, historians and intellectuals developed a sustained challenge to the idea of apartheid as a rupture or break in South Africa’s national history, arguing that the roots of systemic racial discrimination, spatial segregation and white supremacy preceded 1948 by at least three decades. Most commonly, scholars saw the 1913 Land Act and the terms of the peace at the end of the South African War as formal harbingers of what was to come, and the structural conditions established by diamond and gold mining in the 19th Century as the central underpinnings of what became apartheid.

I am part of that orthodoxy, but I’m also grateful that there’s another historiography that underscores the distinctive nature of the apartheid state, that sees 1948 for what it was: a dramatic political rupture, the beginning of a major revision of the political order in South Africa.

For most of the 21st Century, in my public writing, I’ve tried to warn of the dangerous possibilities of an American version of South Africa’s 1948. The central analogy I’ve pointed to followed from the National Party assembled a governing majority after a highly contested parliamentary election despite performing worse than the United Party. The United Party dithered in the wake of the election: they expected the National Party to fail quickly due to their inexperience and extremism. What they didn’t expect is that the National Party would push forward a dramatic slew of legislative and executive changes that not only imposed the strict racial segregation they’d promised but also hobbled the ability of any opposition party to challenge them in the future.

South Africa was still ostensibly a democracy after that point but it was effectively a one-party state, an early example of what is now being called “competitive authoritarianism”, with the additional complication that the majority of the country’s residents couldn’t vote at all. White voters who had opposed the National Party at first mostly went along with them after both because opposition became personally and professionally risky and because apartheid functioned somewhat like an addictive drug: once you’d gone all in on harsh racial segregation and suppression of opposition, you feared even more what would happen if you let up at all. Moreover, the National Party bound many of its voters even more closely to it by dramatically expanding the civil service—in effect, a presaging of postcolonial strategies all over the world for creating an overnight middle-class through government payrolls.

Once that self-reinforcing political order took full shape, what could possibly bring it to an end? The simplest observation I can make is that from the beginning, many whites—and many outside observers—could see the end of apartheid plainly enough, which was that it had a problem of numbers that was insoluable by any means. Small minorities that define themselves in racial, ethnic or religious terms that are highly endogamous, that can’t easily expand to incorporate new members who violate the exclusivity of the group definition, are always on the road to ruin the moment they claim dominion over the political system. At that moment, the menu of options shrinks dramatically. They can facilitate some form of secession or partition that invites the excluded majority to move to a territory the minority is willing to cede. They can offer some form of highly limited—and always revocable—power-sharing in the middle hierarchies of state authority. They can try to keep the excluded majority internally divided against one another. They can brutally attack the least hint of resistance. They can try to thin the ranks of the excluded majority with incarceration, violence, and manufactured precarity, while also trying to recruit immigrants and promote natalism within their own ranks. They can build the capacity of an administrative state to rule through regulation and service provision, extending that capacity through inclusion of the racial majority at the lowest ends of the civil service, and have that capacity increase the dependence of the entire population on state provision while also using regulatory power to make segregation and deprivation more materially manifest, to have the landscape itself enforce the minority’s domination.

The apartheid state tried all of these measures, though not all at once and not equally, because they understood as well as any other minority that has seized power over a sovereign territory that the problem of numbers would bring them down in time if they didn’t find an escape hatch. Apartheid was in some sense distinctive in the post-1945 world not just because of racial segregation or minoritarian power but because of the astonishing systematicity of the state’s attempt to enact all of these strategies for sustaining the unsustainable. The state moved people and destroyed townships, but more banally it built highways, walls, power and water infrastructures, zoning regulations, prisons, domestic spying, policing and legal authority over political action, and much more, that all reinforced its ideology and its practical maintenance of minority power.

The opposition struggled to fully grasp the key point about numbers, in part because it’s one thing to be a majority by dint of exclusion from political and economic power and another thing to act as a majority with strong, cohesive solidarity against all those effective moves that an authoritarian state with this kind of capacity could employ.

The white opposition in the legislature settled quickly into trying to be an impediment to the regulatory state and to be a legitimate source of information about government activities, both of which provided at best a speed bump to apartheid’s unfolding.

The nationalist organizations that set out to challenge apartheid successfully worked the numbers in their favor at first through mass defiance campaigns, but the apartheid state killed 69 people in Sharpeville in 1960 just how far they’d allow that kind of challenge to go forward. As the historian Paul Landau argues in his recent book Spear, the African National Congress’ next move was to plan for a genuine revolution that invoked the favorable weight of numbers as the key feature of its vision, but I think Spear and many other historical accounts make pretty clear that the planners were undone not just by the strength of the apartheid state but by their faith in revolutionary teleology, by their dependence on fixed ideas about models for revolutions, rather than in developing a better understanding of what the numbers looked like from the bottom-up, on the actual conditions and circumstances that might move the biggest numbers of people into putting their weight of their own lives against the ultimately limited capacity of the apartheid state to imprison or kill all the possible opposition to its power.

In the end, the numbers were what mattered.

Activists in the Global North love to give themselves more credit than they’re entitled to for the end of apartheid, in part because that’s how they try to mobilize for campaigns in the present against other targets. The isolation of the apartheid state hurt it, to be sure, often more psychologically than materially, and pushed it into more desperately transparent attempts to fracture the growing cohesion between all the groups excluded from political power. What mattered a great deal in this case was not divestment but the refusal of global finance to roll over loans to South Africa, not because activists demanded it but because apartheid was seen as a risky investment.

The ANC after 1976 and then into the new constitutional democracy it helped to shape has loved to give itself credit by celebrating the armed struggle represented by its own cadres and training camps in the frontline states and its diplomatic efforts elsewhere. The former in particular mattered very little except as another psychological weight on whites who supported apartheid. There’s one military conflict outside of South Africa that did matter, and that’s the war in Angola that involved not just local nationalist militaries but Cuban troops. Whether or not you think the South African military “lost” a key battle in that war, the conflict did put unmistakeable stress on their ability to field sufficient soldiers against potential enemies within the region. Inasmuch as the ANC could claim to be building capacity for that kind of challenge to apartheid, they intensified that stress.

Where numbers were finally put into play was in the internal struggle after the Soweto uprising. By the 1980s, many townships and much of the Eastern Cape had become at least partially “ungovernable”, where the state could only deploy suppressive military and policing power in the face of mass unrest and otherwise lost a lot of its more quotidian administrative presence. What the ANC had imagined as a more orderly and conventional kind of Marxian overthrow without really knowing how to mobilize the masses required for that action was happening after 1976 in more emergent and grass-roots ways. Not without organization, but also not without a rigid imaginary of how party structures, doctrine and mass action should interrelate. Numbers were the central fact here: that there was more territory and way more people than a state dependent on a white minority and their hirelings could successfully keep under control.

I suppose you could also credit a turnover in leadership within the National Party for doing the math in the mid-1980s and concluding that it was time to strike a deal with a reliable negotiating partner before that generation of leaders died off. It’s by no means inevitable that people who have been in charge of an authoritarian political order decide to seek a negotiated end to it when it is starting to unravel, as we’ll see in this series of essays.

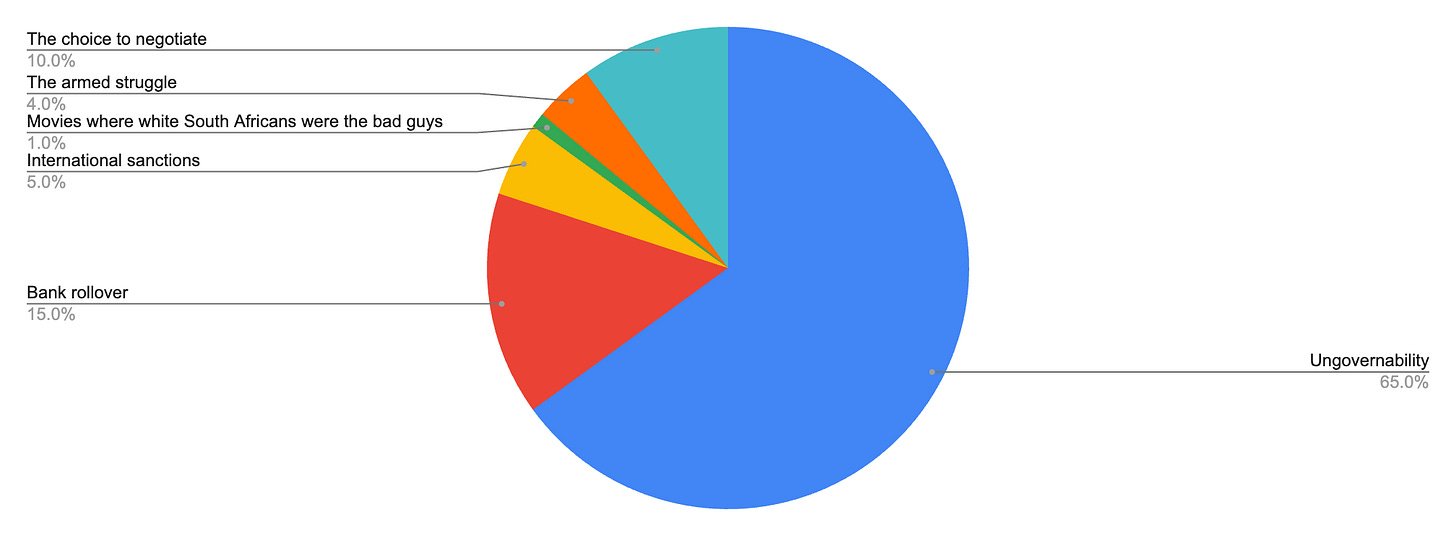

So why did the bad times of apartheid end, after 45 years of disfiguring, destructive, unnecessary oppression? I have a chart for you, based on arbitrary numbers I’ve assigned by impulse.

There is of course also the problem that the bad times arguably did not end, either because apartheid wormed its way into the constitutional order that it helped to negotiate or because it created persistent structures that reproduced themselves after the apartheid state itself was no more. I am personally inclined to say that at least some of South Africa’s bad times after 1993 are global bad times, e.g., that South Africa’s biggest problems have been the big problems of neoliberalism everywhere. Which also means that it’s important not to understate how much of the badness of apartheid did end. There’s a big difference between a state that tore down communities because people with the wrong skin color lived there and a state that is haplessly unable to build communities where it has promised to build them, even if those both end up with people who have nowhere to live.

Moreover, at least a few bad times since 1993 also seem to me to be neither global neoliberalism nor zombie apartheid but particular to South Africa itself—or tracked against other kinds of 21st Century trends. But I’ll get around to Jacob Zuma in this series eventually.

The takeaway for Americans? The history of apartheid’s origins and its end has a few lessons.

Don’t underestimate people you think of as incompetent extremists when they win an election. This might be a lesson that comes a bit too late.

There’s a role for a more-or-less liberal opposition party under “competitive authoritarianism” but it’s pretty small. This is a lesson that I’ll talk about in other histories as well: in these bad histories, liberal parties and liberal discourses tend to shrink to insignificance pretty damn quick if and when the state becomes thoroughly authoritarian.

It’s pretty easy to use civil service expansion to create loyalty to an authoritarian regime. Until you run out of money to pay them.

The more doctrinaire the plans for some kind of national-scale response (revolution, protest, general strikes) the less likely those plans are to correspond with the actual feelings and situation on the ground among the people who will actually need to respond in very large numbers.

Even in the 1960s, it was pretty easy for a state with apartheid’s capacity to spy on everybody planning to challenge it until there were so many challengers that spying was irrelevant. So maybe don’t meet up a farmhouse and keep all the maps and charts out in the open. Assume that if you’re in active opposition that there’s someone spying on you.

Ungovernability requires huge numbers of people to sacrifice their future aspirations and it takes leaders who are right there alongside the people taking those risks in the localities and places where it’s happening. Don’t bother issuing calls to action on Bluesky, etc. But ungovernability (and boycotts) works when it threatens interests who have actual weight of authority that can rival or compete with an authoritarian state’s upper leadership.

The weight of numbers in South Africa doesn’t really scale over to the U.S. situation in 2025: this is pretty much an even split with a very lumpy geographic distribution.

The federal government after January 2025 in the U.S. is unlikely to build the kind of capacity or systematicity that the apartheid state created for itself to accomplish its repressive ends. That also breaks the analogy in all sorts of ways.

Very interesting, very disturbing. But what about the role of religion in both the implementation of the Apartheid regime and in resistance to it? (Knowing who raised me, could you doubt I’d notice this big absence in what you’ve written?) I think we ignore the presence of religious institutions and sectarianism in authoritarian regimes at our peril. Those are often disciplined—in every sense—and highly motivated. And there is no doubt that religion is playing an enormous, even out-sized, role in what is happening in the US today, as it did in South Africa. State-level action is often ideologically informed (or masked) by religious practice. This isn’t simply a matter of laws and legislatures but also of churches and cattle kraals.