As I said, I’m going to alternate Tuesdays (when I’m able) between talking about books I have or haven’t read and doing a re-read of The Journal of African History.

Today’s is going to be short, however, because there are important events which are very much preoccupying my attention today that I will likely write about in the next few days.

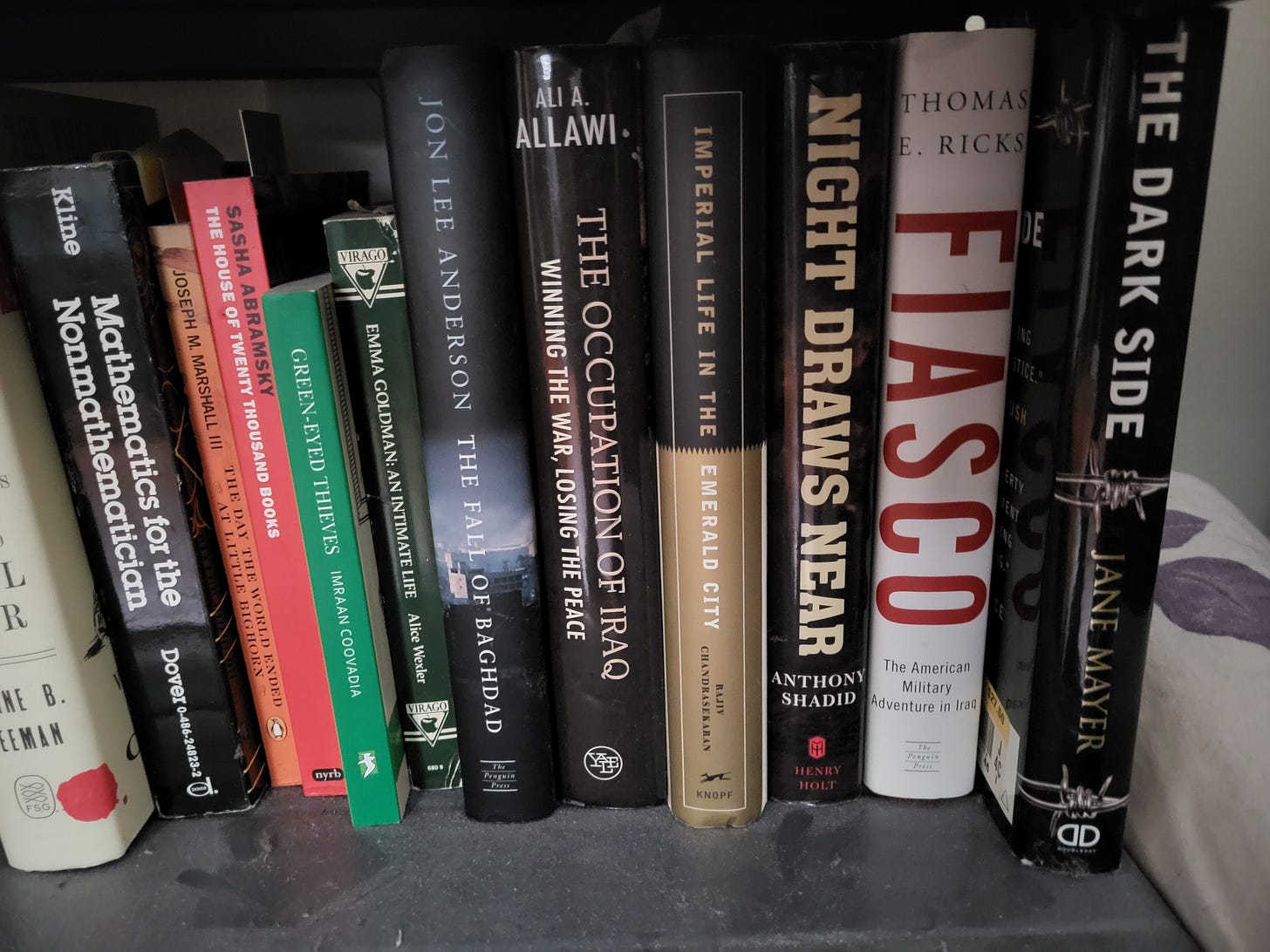

What better then to turn to a section of one of my bookshelves that documents a previous preoccupation, with the war prosecuted in Iraq and Afghanistan initially by the Administration of George W. Bush after the 9/11 attacks?

There’s a few other books that have snuck in there on the left side, and some of my Iraq War-related books are shelved elsewhere (Generation Kill is off to my right as I type) but this is one cluster of the books I bought and assembled at the time.

I read all of these then with varying degrees of interest and investment and I’ve returned a few times to Imperial Life in the Emerald City and The Dark Side.

One of the things I was looking for in this work was a remedy for the initial woefulness of mainstream US media coverage of both wars, but particularly Iraq. I have recounted many times my distress at seeing a writer like Mark Bowden provide pre-emptive cover for torture as we headed into the war, my anger at editors like Bill Keller suppressing negative coverage out of a desire to appear patriotic, and at liberal war hawks (journalists, professors, intellectuals) who ardently called for an indiscriminate war to be fought through illiberal means in order to preserve liberalism.

A journalist friend of mine started a great project at my own institution that got students involved in making very sophisticated journalism that covered some of the gaps in US coverage. But I also thought that these long-form books did a lot to make up for the woeful record of daily journalism. Most of them were meticulous, thorough, thoughtful, and open-minded, exploring all the facets and factions involved in these wars.

What they showed during the war is what we now all know: the war in Iraq was begun under false pretenses, its planners deliberately excluded expert knowledge from the planning process and then from the occupation that followed, there was woeful incompetence at almost every level, and a vast number of completely innocent Iraqis died or were wounded despite having absolutely nothing to do with 9/11 or having no particular animus, at least at first, towards the Americans unseating Saddam Hussein from power. Over time, much the same truths have come out about Afghanistan: that the US was almost willfully incompetent in its target selection and made enemies out of allies and friends, that the parts of the US government that had insight into Afghanistan were kept at arm’s length by the military and the political leadership, and that no one ever really made anything like a plan for what occupation or victory might look like. Not to mention that the utter stupidity of Iraq distracted from the one part of the early operation in Afghanistan might have actually accomplished, which was capturing or killing the entire extant leadership of al-Qaeda. It’s curious that in this moment of total division, one of the few consensus truths seems to be that Iraq and Afghanistan were worthless, destructive, incompetently managed conflicts that accomplished nothing. And yet no one looks back to the start and holds those people accountable (among them virtually every serving elected official in Congress, both parties).

All of these books made me feel queasy, angry, and deeply melancholy at the time. They still make me feel that way, but I also feel a constant dull thudding fury at the people who flat-out got away with their hackery in support of the invasion of Iraq. At least Christopher Hitchens had the intellectual honesty to admit that waterboarding was torture after he experienced being waterboarded. Writers and journalists like Keller or George Packer issued one-and-done apologies, more or less, and expected that to be the end of the issue. (And Packer, if you read his book on the subject, kept finding ways to insist that not only had he meant well, but that he was almost right. That’s the one book in this set I’ve gotten rid of.) Paul Berman showed up the other day when the Chronicle of Higher Education decided he was a great expert to quote about how college students these days glorify violence, without every asking him to square that with him calling for bloody assaults on Islamic fundamentalism and cheering on a war that thoroughly violated the rights of tens of thousands of people who had nothing to do with fundamentalism.

I’d say that this lack of accountability might have something to do with the situation we’re now in. But I’m not sure I even believe in the theory of justice that says that people who suffer consequences for misdeeds learn not to do them again, while others learn not to ever repeat the mistake. And the United States excels at immediately ignoring the fatuousness and carelessness of well-connected men and women who casually cheer on the needless killing and wounding of masses of soldiers and civilians to no useful end whatsoever. We did it for Vietnam, we did it for World War I. “Who could have known?” we’re always told. Well, a lot of us did know and said so before anything happened. And these books said so while it happened, in very precise and stomach-churning detail. Which led none of the cheerleaders to recount or rethink when these books first were published. I often wonder if people like Keller or Berman even read them, and what they thought if they did. Did they quibble and deflect and deny, or did they know even then with dread or regret what it was they’d countenanced, what it was they’d enabled?