Modern political life is haunted by culture.

Culture’s a word that means many things—too many—but in this context, I mean the combination of deeply rooted practices that structure everyday life and basic perceptions of society and the world with a series of somewhat coherent propositional ideas about what is normal, desirable, important, right, or aspirational. Those ideas don’t have to be consistent, they may be hard for people to articulate fully, and they may be violated or ignored in some of the substance of everyday life, but they still distinguish groups of people or communities from one another—sometimes down to the level of sorting neighbors on a single street from one another. Cultures in proximity can intermingle, they can bleed into one another at their edges, they can abrade and repel one another. And one culture can strive to dominate or transform the other, often sharpening the definitional distinctions between them in the process.

Modern political life is haunted by culture because culture produces social agency that in turn informs political action and political desire that the underlying premises of liberal democracy and national identity don’t have room for. The political actor informed by culture is not the liberal citizen rationally appraising their own interests or what’s best for the greatest number of people. They are a person holding to certain ideas, defending certain ways of life, wanting certain things to be true about the world, where the substance of all of those aspirations is formed through an accumulation of historical experiences, narratives, social connections that has no ultimate or reducible cause or ‘real’ interest.

The narrative of so much modern political life—aided by certain styles of social science and political ideology—insists on looking past culture to what people really are, really want. Or it insists that culture in this sense is ideology, false consciousness, brainwashing, astroturfing, noise: either a thing that’s been done to people in order to enlist them as foot soldiers in someone else’s quest to maximize self-interest or that people are doing as agents to distract or conceal their real interests.

It’s not that culture is nothing but itself, that there is nothing to be said about underlying motives, deeper structures, prior causes. But neither is it just camouflage to look past or through as if it weren’t there.

The problem with many educated liberals in contemporary American politics is that their culture is to imagine themselves as being without culture. They have a commanding view from nowhere that lets them see everywhere. Sometimes that means seeing past what looks like culture to whatever they believe to be the real interests of other groups in their nation-state, sometimes that means thinking of the culture of others as something to manage: to nudge it, to incentivize against it, to have trainings about, to edit or correct.

That perspective (itself rather “cultural” in this sense) makes it hard to really get on with politics. It blinds conventional political actors to struggle. Not “the clash of civilizations”, exactly, but at least to understanding that sometimes cultures overlap in a space where governmental authority, legality, etc. have real power and only one culture can have things the way it wants them to be—and that can’t be adjudicated by searching for some form of utilitarian reason that will produce the best policy for the most people. It also prevents conventional political actors from speaking to the cultural formations in those overlaps, or understanding when they are speaking from a culture rather than from some high ground outside of history. When you finally convince many educated liberals that a problem or choice is mediated by culture in this sense and that they also have culture, what they always want at that point is dialogue and understanding. What they have a hard time seeing even when they arrive at that point is that for the culture being spoken to and earnestly understood, dialogue often just looks like the way liberals engage in struggle. E.g., there is rarely any sense at the outset of such a dialogue that one of its contingent outcomes could be the understanding, dialogically engaged educated initiator of the conversation changing their own cultural affiliations.

Not that there should be—this is precisely the analysis that cynical right-wing concern trolls use to guilt-trip liberals and progressives into abandoning or softening their political commitments. They’re not putting their own positions into suspension or opening them up to possible transformation when they noisily complain of exclusions. But that’s because many of these figures are culturally with liberals and progressives in a wider sense—they really are just maneuvering for a greater share of the spoils within that shared cultural world by guilt-tripping their fellow travellers (and threatening alliance with people living in other cultural worlds).

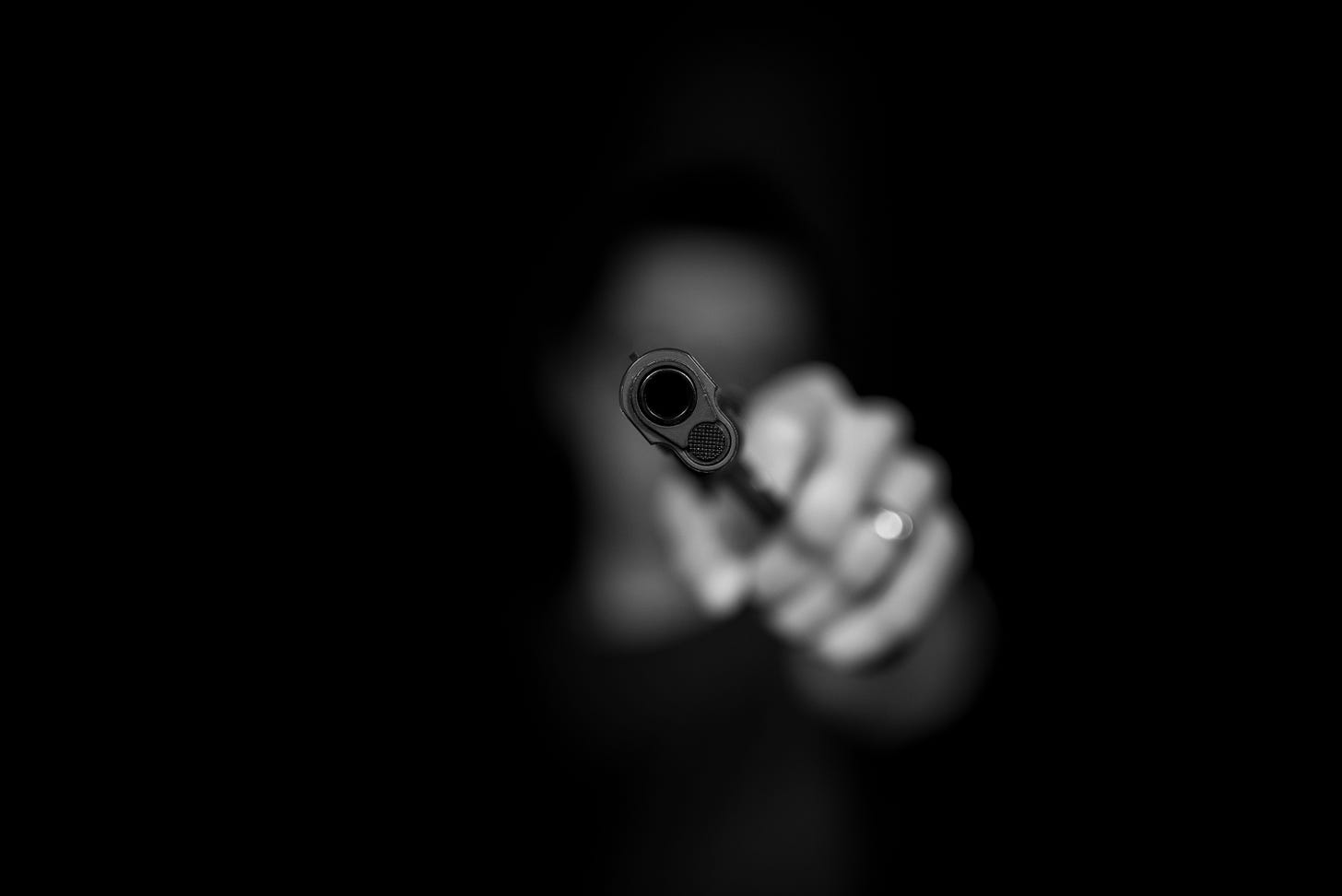

Guns in contemporary America are cultural, and they stand for and structure struggle over one of those spaces of overlap where it’s not possible to make good technocratic policies seen clearly by those privileged to have a view from nowhere.

The fantasy that the overlap can be untangled by policy-making is why we end up with meaningless attempts to regulate particular kinds of ammunition or particular models of guns or bump stocks, as if somehow a sufficiently detailed statute could produce a satisfying quantitative curtailing of excess mortality and we could call it a day.

We search for other ways to escape the bleakness of political struggle over deep cultural formations. We reassure ourselves: it’s just the gun manufacturers pursuing their economic self-interest and doing some ideological manipulation to get there. We try to confine the amorphous boundaries of culture into a single non-intersectional personhood and its histories of social power: it’s white male lower middle-class identity attached to guns as a totem and guarantor of a fading hold on power. (And we reassure ourselves by saying: this is a smaller and smaller number of such men, as fewer people own more guns and gun-centered activities like hunting begin to fade.) Neither of these propositions is untrue, but they’re not sufficient. They don’t provide a more manageable political target that can be subjected to a plausible technocratic policy or some form of paternalistic managerialism.

Gun ownership is a crucial defining icon of culture even for some people who don’t own or wield guns. Much as identifying as an evangelical Christian can be important for people who never go to church, barely know what’s in the New Testament, and routinely violate most of the moral commitments that supposedly define Christian faith. (Indeed, routinely violating those commitments may be what makes that identification so important for some.)

Much as loathing guns is a defining icon of other cultural formations, including the ones I belong to.

It’s not purely a binary, either. There are Americans who do not build guns into a central place in their own cultural infrastructure, but who own and use guns in practical or professional ways, as tools. There are Americans who live with guns and gun violence where the ways in which they practice and struggle over violence and crime doesn’t primarily center on guns as defining icons—a lot of debate within urban communities blighted by drug-related crime over violence may invoke guns, but guns are not constitutive of the discourse about that violence in the way that they are in national politics. There are gun-related social facts that public health experts or epidemiologists would like to push into the struggle over the overlap that never quite seem to make it there—for example, the prevalence of guns in male American suicides. (Perhaps because many anti-gun people uncomfortably suspect that suicide in the United States would not be strongly abetted by an absence of guns, and because those who see guns as an icon of their cultural formation don’t think about suicide as part of that culture.)

The heart of the matter is that people who place guns and gun ownership as an iconic, defining signifier of their cultural vision are not wrong to think that most opposition to guns is not really about the making of detached appraisal of social facts and the making of objectively better policies. It’s about culturally-motivated opposition to the cultural vision of people who make guns and gun ownership a central icon of that vision.

When I think about my opposition to gun ownership, I’m as angry about the thought of walking into a place where everyone is carrying a gun and no one is killed or hurt while I’m there as I am about a 15-year old shooting up his high school. The people who entangle their cultural selves with guns imagine themselves as protecting themselves against a wider society that they fear. They see themselves as acting to prevent future victimhood and overcoming their fears. What I see, in my culture, is that they are making many public and private spaces full of fear for me and mine. A nation full of armed and hostile strangers in many places and spaces who might choose to gun me down if I got in an argument with them, looked at them funny, or just stepped into a business or place that they think I don’t belong in? That’s a fearful nation and I hate it. I don’t want to live in fear forever in that place they want to make, have made.

It’s not really about the people dying in mass shootings or the rates of gun homicides compared to other nations, though that’s important information. It’s about the kind of people we are, about what manhood is or should be, about what makes us safe, about what defines freedom of movement, about what public space means or should mean in a free and democratic society. In my preferred culture, that means not having to think, ever, “That guy could be packing a gun, better not sit down near him” or “That guy is carrying a duffel bag onto my campus, he might be here to shoot people”. That’s not how I feel safe, it’s not how I feel belonging, it’s not how I build relationships to people. And I want my culture to be the one that defines public spaces, public institutions, and how citizens feel safe and secure. I want anyone whose culture includes the idea of being armed and ready to shoot as the preferred path to safety to go into some enclave behind some walls and stay there as long as that’s the way they’re thinking. I’m fine with a cult staying in its compound. I’m not fine with it swaggering down the street and taking over the coffee shop on Main Street where I read the news on my cellphone every morning.

I don’t want legislation restricting a model of gun or a type of ammunition. I don’t even want gun ownership banned. I don’t want gun owners earnestly managed or nudged. I want guns to stop defining a way of being a person and a culture in America. I want people who define the pursuit of their vision of safety through the endangerment of everyone else to cut it the fuck out.

I would have no problem at all with an America full of overlapping cultures that included hunters who shoot animals with guns, hobbyists who shoot guns at glass bottles in the desert, even people who have a unloaded pistol kept in a safe just in case of a break-in. You can have societies with significant rates of gun ownership that aren’t dominated by gun cultures. If we didn’t have a culture that had guns as a central signifier of belonging, the idea of having licenses and mandatory training for gun ownership would be no big deal. You can also have societies that have something like an American style of gun culture where some other weapon or mode of threat is the iconic focus of the culture rather than guns and people live in fear. That’s bad in the same ways even if guns aren’t involved.

I don’t want guns banned or regulated, I want a culture defeated or transformed. Conservative American political life has no trouble talking that way, but it’s just not in the culture of American liberals for the most part to talk similarly. The thing is, you don’t win a rugby game by thinking of yourself as too good to get in the scrum.

Image credit: Photo by Max Kleinen on Unsplash

With academic psychology and allied disciplines that study human behavior dominated by people who share your (and my) cultural outlook, why isn’t there a sort of expert plan for cultural transformation, e.g. on guns? Is it that all the best people at doing practical psychological operations go work for advertising firms, the CIA, or some other institution that’s part of an antagonistic culture? I mean, it doesn’t even seem like there’s any effective infiltration of the online forums where some of the nuttier cultural elements thrive. Are the psychological techniques that are known to work also things that people in our culture would really prefer to believe didn’t work?

As happens all too often in this argument, Tim, you miss one of the major issues of gun violence in this culture: Guns’ use in domestic homicides. Women living in a house with guns present are more in danger of being killed in a domestic dispute than they are anywhere else. (Yes, even if the same women think themselves safer because of the guns that may be turned on them by their partners.) I’m far less concerned with male suicide rates than I am with the rates they pick up those guns and slaughter vulnerable members of their households, often before killing themselves.