The News: Nanny Knows Best

Wednesday's Child Is Full of Woe

Much as I long to think of another way to imagine the constitutive infrastructures of modern life that gets us conceptually beyond the triad of the market, the state and civil society, it takes thinking of some exotic and seemingly unobtainable institutional, technological and intersubjective changes to even begin to envision what that might be like.

Historians who study modern societies know that a lot of contemporary struggles over what the proper balance between that triad ought to be involve a lot of myth-making or even active erasure of the past. As the historian Naomi Oreskes points out in the New York Times, the recently deceased CEO of OceanGate, Stockton Rush, described existing safety covenants and testing processes in the field of travel and research submersibles as regulations designed to stifle innovation and prevent the entry of new competitors into that market. Oreskes goes beyond the obvious folly here, for which Rush has already paid the price, to the deeper (so to speak) untruth, which is that in terms of underwater exploration and travel, government funding and management was the major source of innovation, that risks were incurred by government actors and not private investors, and that the idea of “disruption” or “creative destruction” is simply inapplicable in this case.

Oreskes knows it’s not in just this case, but almost every major technological transformation that has created or transformed an important business sector rests on regulatory activity and government investment. The Internet is an especially well-known example, but there are so many others. It’s genuinely hard to find an example of a major “innovation” that began with a purely unregulated, pristinely private concept, was developed in a purely private setting, and was brought successfully to market without any government sponsorship, assistance, and standards-setting. (I’d be curious to hear if my readers can think of an example, because I can’t.)

It is sometimes the case, as Oreskes observes, that as a given industry or business sector develops towards maturity or even senescence, it becomes the site of a kind of excessive regulatory activity intended to protect some arteriosclerotic monopoly or interest. But a great deal of anti-regulatory rhetoric of the Koch Brothers sort since the early 1980s is often exactly that kind of activity—it’s coming from people who have secured a commanding height in the economy, often with the help of local, state and federal government regulations and spending, and are trying to prevent subsequent regulations from rationalizing or shifting the foundational stranglehold they have achieved. “Regulation” in this less generative sense often comes from private industry and is written by them, not from government that is trying to protect the public interest from private exploitation. The first thing a lot of early monopoly firms did when they got established in a new national market in the early 20th Century was to write up unnecessary manufacturing standards that would constrain some of their undercapitalized rivals from getting a toehold in that market, and that’s remained a problem ever since. The issue there isn’t regulation qua regulation, it’s allowing private money to suborn public interest. Getting rid of regulations to solve that issue is like burning down the whole forest to deal with the problem of fireworks setting off brushfires.

I’ve long valued a thought I originally got from James Livingston many years ago that there could (and should) be a way for critics of capitalism to appreciate markets as a structure of distribution, since anything like a command economy that requires active human decision-making for all allocations of resources and all supply of commodities is plainly going to end in tyranny. In that sense, maybe even the idea of business in a market structure—an impersonal institution that is using supply-and-demand to route goods and supplies—is attractive or useful.

But it’s plain that capitalist markets that are unconstrained by the state or have no set responsibility to the public interest are always going to trend towards the forgetting of the state’s role in the creation of innovation and the maintenance of secure conditions for doing business—and that they are never going to be able to act as genuine stewards of human needs and wants. At the heart of modern life, this is one of the worst lies that we tell ourselves, or allow people to tell us—that if market capitalism was just allowed to function properly, then everything that people want would be produced and available in the most frictionless way possible to the necessary and materially plausible extent that it could be.

Take the most effective drug treatments available for many cancers that are presently on the market. They are in short supply, to the point that some patients can’t get them because prescribing doctors are having to decide on their distribution according to triaging. In some sense, these are the “death panels” that the tribunes of “free-market capitalism” threatened us all with during both major attempts to reform the American health care system, what those critics claimed would be the inevitable result of an expanded government role in health care allocation. But it’s the market, in the end, that’s at the root of the problem. Perhaps not quite in the way most people would expect—this is not the same as the truly disgusting price-gouging that the company Mylan engineered in the sale of epipens or in the sale of insulin (where the greed is more evenly distributed up and down the distribution chain).

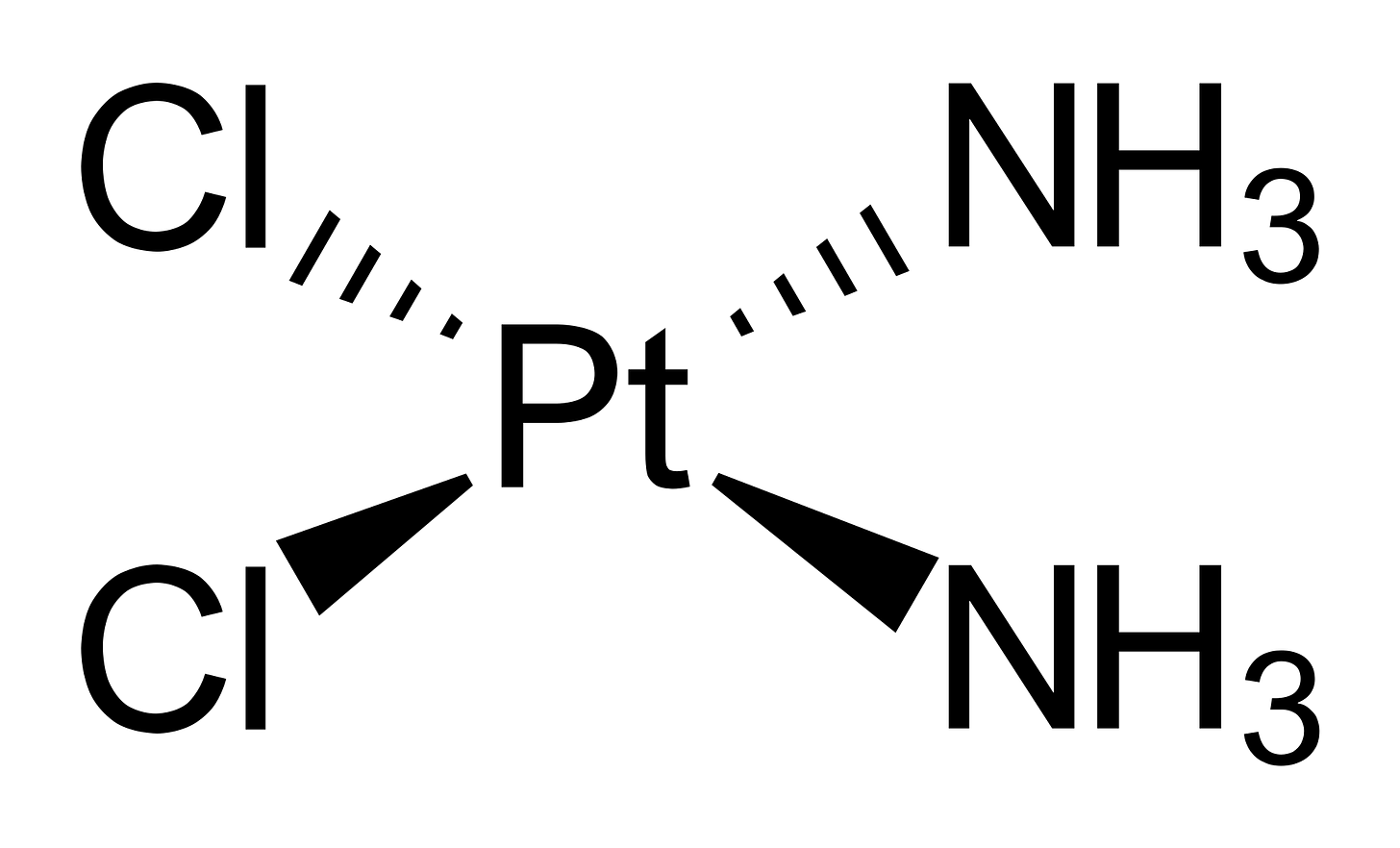

Unravel the details here. Government restrictions have some role in the shortage: there have been constraints on importing the drugs in question from China in part because of concerns about whether the drugs are being manufactured properly there. Cisplatin and carboplatin, the drugs in question, need platinum, a highly sterile manufacturing environment, and according to the NYT article, protections for the workers from the toxic effects of the drugs. But that alone, the NYT and its sources observe, is enough to discourage most manufacturers from getting involved, no matter what the need is. So it’s left to factories in countries that do not really enforce (or even have) regulations, which means the product isn’t actually what prescribing oncologists and their patients expect. Hence the FDA has restricted imports or inspected some facilities abroad, which has led to the constriction of the (inadequate) supply coming from those sources.

So imagine a fairy-tale free market solution to this: no regulations at any point, just caveat emptor. You’d need a good oncologist—and to be able to pay them for their expertise—who would safeguard you by insisting on a reliable product with a reliable supply chain. The price for the drugs would have to be whatever the market requires—if it’s expensive to produce them safely and at high quality, you’d have to pay for that to as the end consumer.

These are efficacious drugs for some cancers, so you aren’t chasing a placebo or a long shot here, you’re trying to buy a serious chance at an extended life. Which is the heart of the problem, in the end, as we’ve known for a long time. Arguably as human beings have known long before modern capitalism. What would you pay to live longer, in good health? For most human beings, the answer is anything. It’s the textbook example of price inelasticity. If you have to have it—the real, well-manufactured, actually-effective drug—then you will pay anything. It doesn’t matter whether you lift every regulation in the world and let the invisible hand work without fetters or constraints if the goal is to make the drug always available to all the people who need it. It’s not clear that most companies would actually care to go to the bother of making it even so, because the number of people who can pay anything in a world that is completely unregulated and ungoverned is likely fairly small, and there are other inelastic goods where there is more anything profits available without having to do much of anything to make the goods in question. In an unregulated world, you can charge anything for opium too, and there’s more people who will give you everything they can once they’re hooked on it. Cancer patients? Eh, some of them are going to die in short order anyway, so why invest in a safe manufacturing process at all? A wide-open world is full of short, easy paths to riches. If there’s no other imperative to secure human needs, to ensure human flourishing, it won’t happen through unconstrained profit-seeking and self-interest. Self-interest does matter—it is arguably the rocket fuel that has made modernity as efflorescently creative and materially abundant as it is. But it only works within the triad we have, checked and balanced by other imperatives and institutional channels.

There isn’t a world where we get these two drugs at reasonable prices in adequate supply for everyone who needs them without regulation, without the state, and without an overriding sense that the public interest matters. That’s how it was discovered in 1969 that a compound first identified in the 19th Century showed promise against cancerous tumors: a tumor line was provided by the National Institute for Health, following research standards of the U.S. Congress-created Cancer Chemotherapy National Service Standard, and funded by the National Institute for Health and the United States Atomic Energy Commission.1 Funded by government, shaped by government-backed laboratory standards, using resources stewarded by government agencies. You never get to the world where cisplatin and carboplatin are being shortchanged by private industry without the state’s funding, the state’s acceptance of risk (e.g., underwriting lines of basic research with no guarantee of profitability or usefulness), without the state’s standards.

People might settle for Stockton Rush taking his own risks, or worry very little about the kind of people who might join him. But we can’t settle for a global system that shrugs off any responsibility to affordably and reliably produce drugs that can save so many lives. It so happens that in both cases, the wellsprings of innovation and possibility have been the state, not private industry. That is yet another of the obviously true histories that some people have done their best to erase and obscure in the last four decades.

ROSENBERG, BARNETT et al. “Platinum Compounds: a New Class of Potent Antitumour Agents.” Nature (London) 222.5191 (1969): 385–386.