There have been all along two predictions about Donald Trump’s political future.

That something he has just done “may yet carry a political price”, that this time he’s finally in trouble.

That he could shoot a man in broad daylight on Fifth Avenue and not lose any voters.

So far #2 is batting a thousand and #1 has whiffed every pitch it has faced.

The mainstream press and punditry, who are the usual batters at the plate on #1, don’t seem capable of grappling with their endless predictive failure. Cynics observe that they don’t have a strong incentive to figure it out inasmuch as Trump is good for business, but I think a lot of these famous, self-confident mostly-men would just as soon be correct about Trump and move on to the next big story they can get mostly wrong.

I think more that understanding why #2 is correct requires crossing some intellectual and analytic lines that mainstream pundits are predisposed to stay away from.

The first is that Trump’s voters are not so much in love with Trump’s ideology as they are in love with his meaning, with his semantics as a person and a political figure. What they love is how much he is hated, how much he provokes, and whom it is that hates him. I grant you that some pundits do seem to grasp this much. (The Will Bunch book I wrote about last week is very on-target in this respect.) Everything Trump does to aggravate the people who hate him—and I’m one of them—makes him more alluring to his voters, and it is the stylistics of what he does that matter as much as the content. DeSantis can do even more than Trump in terms of advancing his agenda, but the Trumpists still read his outward demeanor as Ivy League technocrat. Ted Cruz can pretend to be folksy, but the base is not fooled. Trump’s incoherence and irresponsibility, his word-salad reprocessing of the glossolalia of right-wing social media and miscellaneous chum-bucket repositories of misinformation is real. It sounds like home for many of his supporters and it makes college-educated urban and suburban liberals and progressives so crazy. That kind of winning they are not tired of.

Against that backdrop, he can literally do no wrong. He could have said that actually he did assault E. Jean Carroll and so what, and it wouldn’t hurt him. It might even help him. There is nothing that can happen to him through the courts that does him political damage in this sense, which is about half of what the pundits are thinking of when they predict that he may “pay a political price”.

Until or unless he is ruled legally disqualified for running for office. I’m among the many people who think Trump should long ago have faced the most serious legal consequences for his actions. But it is no accident that the kind of proceeding that has descended quickly on George Santos has so far kept out of Trump’s path.

The question is why? It’s plain that any liberal democracy that soft-steps around an undisguised, sustained, serious attack on its central premises is playing a dangerous game where its existence is at stake. The hope is plainly that somehow the threat will simply fade away on its own. That has not happened very often, but then again, these circumstances are not in world-historical terms all that common.

The deeper reason for relative inaction has to do with the other half of the thinking behind “maybe this time he’ll pay a price”. It’s the question of how interests within the state that are otherwise rivalrous or competitive manage to trust one another enough to agree to coordinated action that can’t ever be agreed upon overtly or explicitly. I suspect the people inside the DOJ are in many cases investigating less the specifics of charges against Trump and more investigating, in all the indirect and implicit ways possible, whether the whole apparatus of the DOJ will be behind them if they do, if the judiciary will stand with them and enforce the law as it ought to be, if the upper leadership of the GOP will just make routine noises of outrage but otherwise stand aside when the crunch comes.

The state is essentially investigating itself: if it has to confront a rising tide of authoritarianism, is it strong enough to survive the confrontation? Are its sources of civic and social support deep enough? And the problem is that the wrong time to ask whether the seawall is high and sturdy enough to survive a hurricane is as the hurricane arrives. The fact that we have a rising tide of authoritarianism is already prima facie evidence that the state is weak, the democracy is sick, and the social foundations supporting both have structural problems.

It’s worth looking outside of American history to see what the circumstances are where it becomes possible to investigate and potentially jail a former head of state for substantial criminal misconduct, including attempts to undercut the government itself.

Revolution or a coup d’etat, e.g., the violent seizure of the state by forces opposed to the former head of state. In the last 250 years, I think it’s fair to say this has been the most generally common way that a former leader ends up charged with crimes. Or in some cases, simply judged a criminal and dealt with, without any judicial botheration. You could throw “losing a war” into this category too, I think.

Mass protests and general strikes that create such a sustained feeling of crisis (and the dangerous possibility of the seizure of the state) that a head of state accused of crimes judges it prudent to flee to a presumed safe harbor, at which point they sometimes end up tried for criminal offenses in international venues or extradited back to their country of origin. Mostly not, but in any event this leader is at this point no longer leading and there is now generally a strong consensus in their former country in favor of criminal prosecution should the leader return.

Mass protests and general strikes that force existing institutional mechanisms for removing a head of state into action in order to restore order, and which immediately lead to the prosecution of the removed head of state.

The threat of mass protests is felt strong or imminent enough that it gives judicial, legislative or institutional actors sufficient motivation to pursue action that they might otherwise have deemed too risky or tenuous.

Note that if you deem all of these unlikely regardless of further developments in the contemporary American case, unlikely under any circumstances, one of the major driving forces that sometimes pushes judicial, legislative or other institutional actors to move against a politically protected target is off the table.

Prosecutors from internal jurisdictions where the former head of state is politically weak feel able to proceed with judicial action without fear of being overruled by national-level actors and have sufficient leverage that their criminal or civil proceedings against the former head of state will have consequential effects on the accused rather than just be symbolic actions. Or in some cases, foreign jurisdictions, as in the case of Spanish judge Baltasar Garzon’s arrest of Augusto Pinochet for human rights violations committed in Chile. This is pretty much the way things are shaping up for Trump so far—he’s not wrong in some sense to say that he is exposed to judicial action in New York in a way he wouldn’t be in Florida or Alabama.

When there’s a general reform movement under way and a solid sense that a political transition from past misrule has been accomplished. E.g., prosecutors wait until it feels safe to move forward and where the political opposition to prosecution has gone dormant. As I said, I think that’s the track some of the investigations of Trump are on—they’re waiting for a change that is plainly not in the offing, and they’ll wait and wait until it somehow magically happens.

When a single determined actor in the judicial system decides to roll the dice and forge ahead regardless. Often this person comes off like a kook or a fanatic (Jim Garrison, say) but sometimes they pull it off and effectively assume all the risk that everyone else was too frightened to take on—sometimes exposing that there was less risk than everyone thought, that the former head of state and his supporters were paper tigers.

When a group of actors makes the same judgment call, sometimes waiting for a moment of temporary opportunity where the target seems weak, vulnerable or exposed.

Safety in numbers: when prosecutors swarm the field and figure that at least one accusation will make it through. (This depends a bit on having a former head of state who is obliging enough to have committed many possible crimes.) This is more or less the approach that the Italian judicial system took to Silvio Berlusconi, who was protected in many of the same ways that Donald Trump is protected now.

When the call to act comes from the political leadership, overtly, rather than judicial institutions—where there is a decision made that a former head of state represents a threat that requires some direct action besides arrest and prosecution. (In countries with more capacity for unconstrained executive authority, this might include forcible internal exile or expulsion, or it might entail some form of direct threat made to the person of the former leader.)

It’s a pretty gloomy list because it seems plain that almost none of these options are in play in the case of Trump, and those that are tilt towards risk adversity and avoidance. These are really the only considerations worth looking at now, in any event. Trump will never “pay a price” in the sense that the punditry means: his supporters will always stand with him, and his notional allies will be too afraid to abandon him while that remains true.

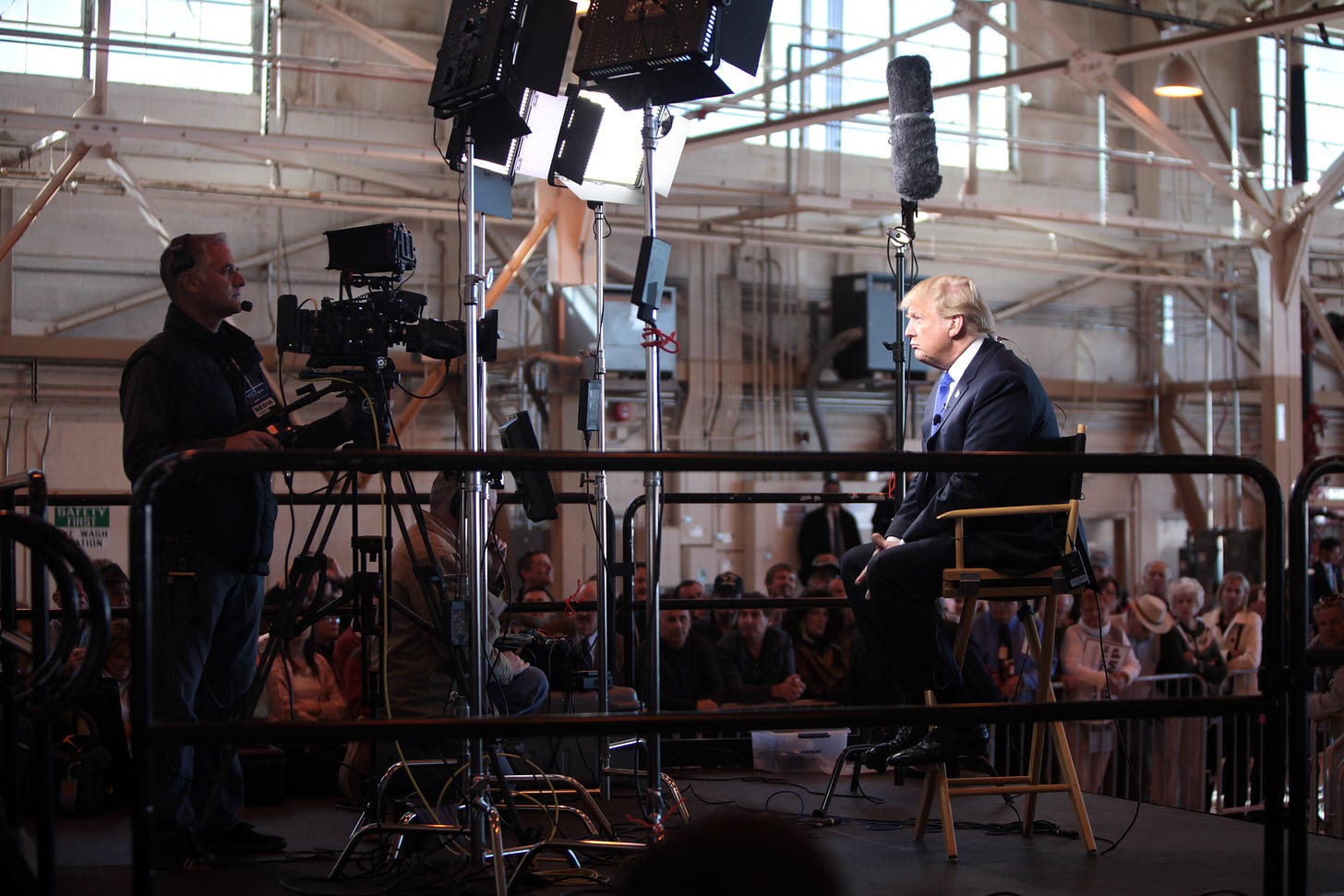

Image credit: "Donald Trump" by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

This is an incredibly comprehensive treatment of the situation. I’ve thought that MSNBC has really monetized #1 to the point that there is no advantage to #2. I wish Mr. Mueller had taken one step outside his lane...my fantasy.