The companies producing film and television plainly intend to win the war against human labor even if they lost the battle in their recent strike negotiations.

It’s true that the market for new content would be depressed somewhat regardless of the state of labor relations within the industry. The pandemic has left a lasting impact on movie theaters (though their basic business model has had problems for decades), a glut of streaming services has strained the willingness of consumers to pay for more content and has fragmented the market overall, and audiences are plainly tired of some of the major franchises and the variable quality of new programming associated with them.

But I also think that the heads of the increasingly small number of major companies are determined to make a point after the strikes. They’ve got reserves (of cash, of content, of resources) and are in no hurry to put people back to work. And regardless of what was in the contracts they signed, the top executive ranks are also plainly looking ahead to the day when the only human beings on the payroll besides the C-suite will be low-wage minders cleaning up the work of the AIs that are churning out the real-world 21st Century equivalents of Ouch My Balls!, T.J. Lazer, and It’s Not My Problem: disposable, repeatable, formulaic ways to waste away some time.

I think they’ll still need real writers doing challenging and well-compensated work for a niche of expensive premium content intended for wealthier audiences that will pay for it, and those productions will also require skilled staff who have real expertise with the relevant technologies needed to make high-value visual culture.

The people I think should really worry are the actors, because each passing year, Hollywood is showing more and more interest in and facility with making the dead rise from their graves and act on the screen.

I could care less about spoiling the latest Alien movie, but if you do care, read no further.

Apparently the android character played by Ian Holm in the original film returns in this film. That makes sense within the Aliens universe, since he’s an android and we know there are multiple copies of the same model. But it takes a deepfake to make a dead actor show up again. It’s hardly necessary for the film itself in the sense that if you’re a fan of the Aliens franchise, you know full well that the corporate maker of androids and synthetics is up to no good, but you also know that their artificial beings have exhibited a range of moral behavior and do not always follow the company line. A new Aliens film can play all sorts of interesting narrative games with synthetic characters without having to use a dead actor’s likeness.

This is yet another tech demo in a series of them, and plainly this is a domain where both the official mainstream and the darker underbelly of digital culture are converging on the ability to make convincing visual simulations of real people doing pretty much anything a content producer wants them to do.

Even if future contracts demanded by the small number of actors with real industry clout expand their likeness rights to prohibit their use after their death, the graves are sufficiently full of bankable stars who never had the chance to forbid being forced out of their tombs.

I’ve got no problem with recasting characters in intellectual property that has continuing value. If you can find a new Sherlock Holmes, a new James Bond, a new Dorothy Gale, then why not a new Captain America, a new Luke Skywalker, a new Gandalf? Go right ahead. That’s a venerable art that has provided work for generations of actors. It is an engine that makes culture new and interesting, in fact, by showcasing what a new actor can find in a character that others have played. It’s not just for Shakespeare.

But there is something awful and unsettling about compelling the dead to appear as a character they played while they lived. There’s a narrow band of simulations that we’ve long accepted precisely because they are plainly dead things and copies: animatronic presidents at Disneyland, wax statues at Madame Tussaud’s, Ben Franklin re-enactors at Independence Hall. A deepfake simulation of a dead actor in a film or TV show, even a brief cameo, has only been tolerable and barely that because the uncanny valley still guards us against a reanimated army of unconsenting workers.

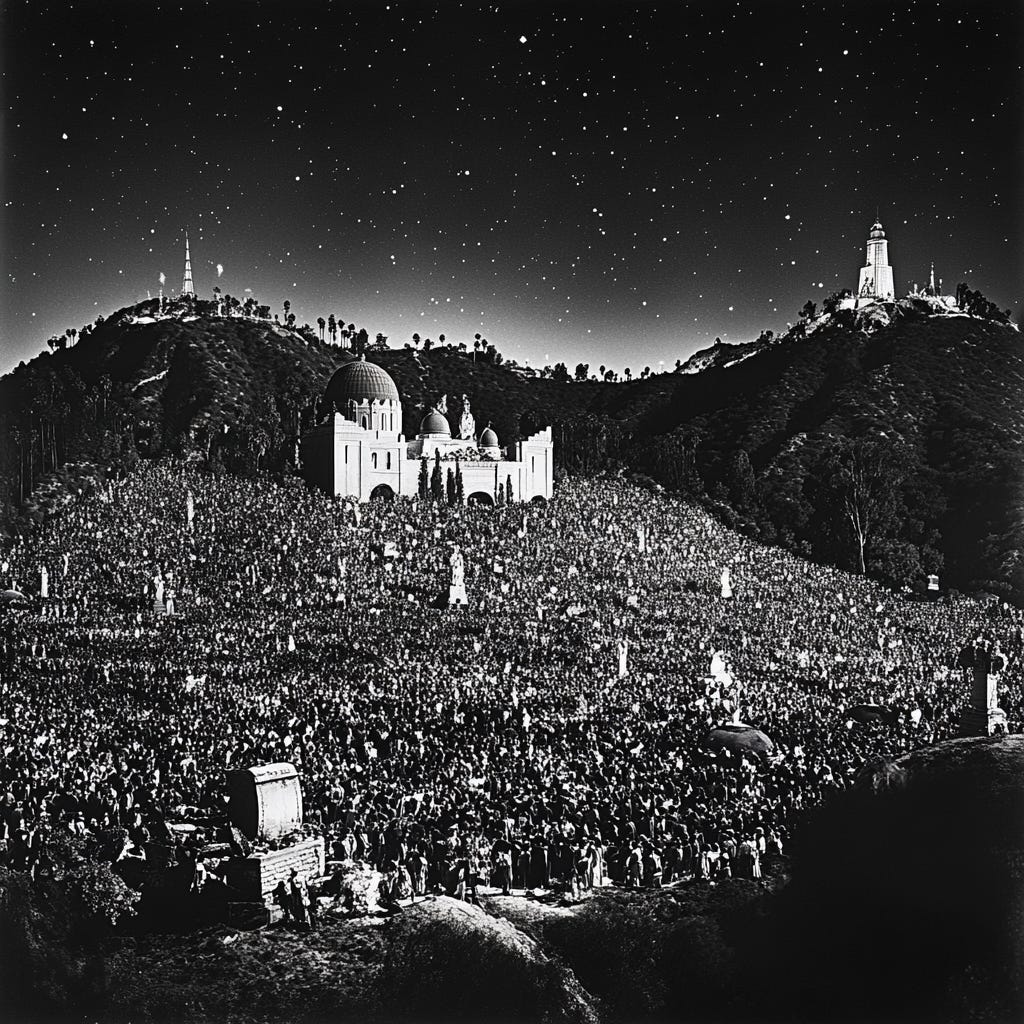

It’s not just about making people who never said “yes” do things that they are not humanly there to permit or commit, and all that might follow from that final reduction of people into contracts. It is that this flirtation with deepfakery comes from the same place as the fantasies of immortality that are so beloved of Silicon Valley’s oligarchs. It is a fear of change: of having to find new people to act, of having to pay new creative talent as much or more as you pay them today, of the risk of making new culture. The people in charge right now want the wheel to stop rolling forward. They want things just as they are forever, to lock their vaults and rob all the graves contained therein. They own thousands of stars, and they figure that soon enough they’ll have a million likenesses for crowd scenes and background characters.

Hollywood is here another example of late-stage asset capitalism. You don’t make money from making what customers want any more. You make interest off of what you’ve already accumulated. In this case, that means never-ending necromantic rituals in the boardroom: Star Wars XVII with Clark Gable and Peter O’Toole as Jedis, the next Game of Thrones spin-off with Sidney Greenstreet as an unscrupulous inn-keeper. No actor ever dies ever again, though the culture itself will be in a coma, barely breathing on a respirator.

Yes it's crazy! Is culture even worth this cost!? Just a very dark world where the masses are entertained by mindless computers operating with only the shallowest of direction from real human beings.