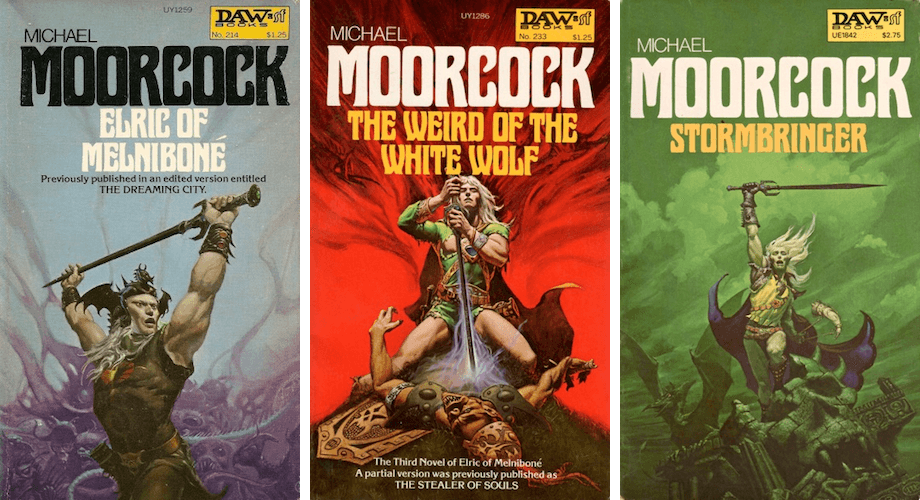

Periodically I see news that someone’s going to make a film or a TV series based on Moorcock’s Elric books. I live in times where much of what I read as a young person has become fodder for such adaptations, to my very great surprise. And yet I’ve wondered whether the memorable but fragile alchemy at the heart of the Elric series can survive a transition to another medium.

I feel more optimistic after a re-read of Elric of Melnibone. Moorcock’s whole style and mood feels indelibly tied to the 1960s and 1970s, but the Elric series has some enduring appeal to it. The first book in the series was not actually the first written—it’s actually something of a prequel in its way. Elric developed in that sense rather like Robert E. Howard’s Conan or Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser, as a complete character concept whose life gets told as a series of shorter adventures. Unlike them, Elric does have a distinct beginning, middle and end to his life and he is surrounded by portent and prophecy.

What felt astonishing to me when I first read the books around 1976 or so (I read them in the series order, not the order they were originally published) was the central character: a moody, depressive young emperor of a realm that has slowly retreated over centuries from its former imperial dominion back to its heartland. He’s a physically weak albino who has to take drugs to maintain his vitality who presides over a decadent, sinister court of not-quite-human Melniboneans who have practiced human sacrifice and use sorcery to summon demonic beings, elementals and creatures from other dimensions. He’s got an evil cousin who is trying to take the throne from him and a beautiful cousin that he’s in love with.

Even now, you’d generally expect you were being set up for the birth of a heroic figure who rejects the evil ways of his kingdom and either fights for its reform or leaves his throne for a more righteous life as a wanderer. That’s vaguely right but substantively wrong. That much is clear in an early scene in this book where Elric is summoned because some spies from Melnibone’s enemies have made it through the sea maze surrounding it. Elric indifferently pulls up a chair while his head torturer slices the genitals off of one of the prisoners and tortures the rest. Moorcock works a bit too hard to try and instruct us in how to see this scene: “It was not that Elric was inhumane; it was that he was, still, a Melnibonean. He had been used to such sights since childhood. He could not have saved the prisoners, even if he had desired, without going against every tradition ofthe Dragon Isle.” There’s a hint of authorial nervousness visible in the early part of the book that I think underscores just how startling Elric felt as a character. Even when Elric later indicates his sympathy for Melnibone’s former colonial subjects and acquires a more conventional kind of motivation for a protagonist (revenge against his cousin after being betrayed by him and rescuing his beloved from him), Elric remains a thoroughly Byronic figure—impulsive, sentimental, obsessive, full of dark urges and emotions, and doomed in various ways to betray those loyal to him—but also perversely merciful, tender or altruistic at unpredictable junctures.

The most important source of his doom is Elric’s other striking fictional legacy: he eventually gets his hands on a sentient black sword called Stormbringer that lets him stop taking his vitality drugs—because the sword feeds him energy from the souls that it takes from those whom Elric kills. The first time he lifts the blade, it feels as if a thousand heavy metal albums have burst into song.

I think Elric’s stories were the only really successful ones built on Moorcock’s overall concept of “the Eternal Champion” who is fated across many realities to fight for reasons that he never fully understands and to restlessly wander the world. Often the Champion works to free humanity from the domination of gods or supernatural beings.

The other versions of the Champion just never felt very compelling to me by comparison—Corum, who is essentially the last survivor of a genocide; Hawkmoon, who fights against a fascistic, sorcerous Great Britain that is set to conquer the world; and many others. It’s sort of unfortunate that Moorcock only began to experiment with version of the Eternal Champion who were women or genderfluid much later and mostly as minor characters: that might have been a good way to mix up or enliven the series. But also Corum and Hawkmoon are just kind of droopy and generic by comparison with Elric—they never really seem to have fully-realized personalities of their own. (Hawkmoon has a good supporting cast, though.)

Elric’s stories have a great mix of one-and-done adventures and the gradual unfolding of his overall destiny. He’s got one of the best companions in the Eternal Champion books, a cheery thief named Moonglum, and also a fantastic recurring adversary, a wizard named Theleb K’aarna. On re-reading, I also was reacquainted with the great world-building that Moorcock does around magic in this series, which almost entirely involves summoning dangerous spirits, creatures and demons and invoking various long-standing compacts or obligations. After reading several of the books in the series again, I found myself very much wanting to see it get adapted for TV or film. I suspect many younger viewers or readers would find Elric familiar, given how much his fictional DNA has seeped into subsequent fantasy, but the books still have a feeling of startling originality.

Wendy Pini, of Elfquest fame, published her artwork from an unfinished animated movie project that she did based on the Elric books. It was called "Law and Chaos", and it might be hard to find. It's fascinating. Also, Moorcock's later entries into the Elric world (starting with "The Fortress of the Pearl"), have a much less...inhuman...Elric. He seems more explicitly a "good guy" and to have a distinct moral viewpoint.

These books meant a lot to me as a young adult, but I haven’t read them in many years. I do remember Elric (and his sword) as the best of Moorcock’s motley crew, though. I’d be interested in seeing how they translate to the screen, as well. Now if only somebody would do the same for Tanith Lee, who was (in my mind) Moorcock’s young companion in those days.