Besides what I had to say yesterday, there’s another issue really nagging at me about James Sweet’s comments on historical scholarship and historical thought that I want to come to grips with.

Sweet writes,

This new history often ignores the values and mores of people in their own times, as well as change over time, neutralizing the expertise that separates historians from those in other disciplines. The allure of political relevance, facilitated by social and other media, encourages a predictable sameness of the present in the past. This sameness is ahistorical, a proposition that might be acceptable if it produced positive political results. But it doesn’t.

In his conclusion, he returns to this point (as he does several other times in the essay):

Doing history with integrity requires us to interpret elements of the past not through the optics of the present but within the worlds of our historical actors. Historical questions often emanate out of present concerns, but the past interrupts, challenges, and contradicts the present in unpredictable ways. History is not a heuristic tool for the articulation of an ideal imagined future. Rather, it is a way to study the messy, uneven process of change over time. When we foreshorten or shape history to justify rather than inform contemporary political positions, we not only undermine the discipline but threaten its very integrity.

This thought is a familiar one. In my experience and the experience of most historians, it most often arises as an objection to judging the slave-owning leaders of the early American republic by contemporary standards, but it is also a highly mobile objection applied to almost any pastward conduct or practice that contemporary people might deem distasteful: Roman spectators watching gladiatorial combat, Aztec sacrificial rites, classical Greek pederasty, public executions in early modern Britain, colonial conquest and genocide. A long list, shifting as the present does.

That is Sweet’s first problem, and it’s a bad problem for a historian to be evincing in an address to other historians, which is the presentism of his critique of presentism, even within the historical profession. Historians have been deeply involved in these discussions about judging past conduct by present standards, and on all sides of the fence.

The question is often both philosophical and empirical in the same moment. Did Roman spectators see the violence of gladiatorial conduct within a completely different frame than we do, as a spiritual experience, for example? Did they not imagine “violence” in the same categorical ways that we do and hence cannot be judged depraved in their own terms or even perhaps in ours? There are scholars who’ve argued both propositions. But flip the example a bit and a new question shakes out: maybe the gladiatorial contests weren’t quite so violent as our common vision of them? Maybe a lot of the deaths and injuries were fake or performatively exaggerated? Maybe the spectators were in on that truth? Which lets you turn it over again: well, and who are we to clutch our pearls and say “how horrible, watching men fight one another for fun”. We watch sports that pretend to be fights and sports that conventionalize fighting. We watch videos of real people dying in war and we watch films where monstrous people and literal monsters violently murder people in highly realistic ways. We force ourselves to look at photos of a little girl whose flesh is burning off from napalm and photos of genocide victims in ditches because we think we need to confront that truth. Flip it over again: well, maybe some Romans enjoyed a good gladiator fight and some didn’t; maybe they disagreed about what was legitimate and what wasn’t. You can find historians thinking about all these points, and a good ways back.

It’s hard to say “well, the Founding Fathers were just different, it was a different time” and yet say, “Let’s go read the Federalist Papers and learn some valuable things about our government today.” It’s harder to invoke the presumptive alterity of Thomas Jefferson’s moral thought and yet read his own words and see that he himself was uncomfortably aware of his contradictions. Still more to see that some of his contemporaries were profoundly aware of his contradictions and called him out on precisely this point. If you want to make the past out to be so foreign a country that we must approach it as alien and unknown (save for the labor of expert historians), you don’t get to say “well, except for this and that and that, which are in fact quite easily understood by contemporary people and very relatable”. That, dear friends, is a political move and I don’t particularly care for the politics in it.

But this is familiar ground in how publics and historians justify a judgment on the past, recent or distant, and it has been familiar for a long while. Sometimes we say: because the past lives on in the present, because the past caused the present, we are right to judge it. Sometimes we say: because there is a present institution which can properly be held accountable—legally, politically, socially—that has been in continuous existence from a past to the present, we can rightly call that institution to account and demand that it repair what it did back then. You don’t get to celebrate the glory of your antiquity while shedding the ignominy of it. Sometimes we say: because we’re all human beings, we know a wrong in the past as surely as we know it in the present; if the past is a foreign country, it’s a neighboring one, where they speak the same language but just spell things a bit funny. These are not new thoughts nor new trends nor the end of the historical profession. These are in fact the urgent, important and interesting conversations that are our bread and butter, our raison d’etre. If Sweet is worried about the survival of disciplinary history, he ought to run with joy into those discussions and hope to see his colleagues inhabiting all sides of them, rather than dourly warn us against them and caution us to leave the field.

Let me dig in a bit deeper here, right on the specific case that I think is troubling Sweet’s mind the most, in the strange middle of his address, where positions himself and proper-thinking historians looking to preserve their expertise between two oddly drawn extremes: American conservative culture warriors on one hand and on the other Black people on heritage tours, Black intellectuals shaping the 1619 Project, and Black actors and creators making the upcoming film “The Woman King”, about the kingdom of Dahomey in West Africa at the height of the slave trade.

So let’s talk about Dahomey. I completely know what Sweet is getting at when he wants to warn us to understand people in the past as they understood themselves, to study past societies on their own terms rather than our familiarized, contemporary version of them. If he made that appeal in some other context, I’d likely agree with it as an intellectual imperative, and so would most specialists in African history.

But the reasons we would agree are not self-evident nor blandly professional. They’re deeply implicated in a politics that produced this objective as an important professional and intellectual priority. It’s just that it’s a politics that arose in the present of the 1970s and 1980s, a past presentism.

You could study 18th and 19th Century Dahomey with no interest whatsoever in how people in Dahomey thought or felt. No interest in their practices, their cultural and social world, their religion. 18th and 19th Century European observers took something of an interest in Dahomey’s culture and politics, but often for practical reasons (if I may be permitted to impose a contemporary framing of motive on their subjectivity), namely, they wanted to buy slaves and sell commodities in Ouidah and elsewhere and they needed to understand what Dahomey and its rulers might do and want. But later historical studies could simply regard Dahomey as something acted upon by systems, forces and causes contained wholly within Europe and its New World settlements, and some did just that. You could decide Dahomey only mattered in Atlantic history as a source of slaves, as an economic input, as something that could be counted. You could judge that nothing that any West African polity did, deliberately or otherwise, had any real impact on the Atlantic slave trade as a whole and therefore there is little about the internal affairs of such societies that merits study.

From 1900 to the 1930s, the only historical attention Dahomey received from white Europeans or Americans was from colonial administrators, for instrumental reasons. The first modern white American scholar to write about 18th and 19th Century Dahomey as a historical subject meriting its own attention, as being interesting in its own right, was Melville Herskovits, in the 1930s, but the kind of interest that Sweet calls for (and exhibits in his own scholarship) is a much later thing, really beginning in the 1970s. Black intellectuals in the diaspora and West Africa, on the other hand, took an interest in Dahomey’s history early on, a sometimes troubled interest, precisely because they envisioned it as the West African polity most identifiably involved in the Atlantic slave trade.

I wrote about Herman Bennett’s African Kings and Black Slaves a while back, and I want to pull in Bennett’s insightful characterization of an intellectual turn in Africanist scholarship that I think Sweet inhabits and is referencing in his call for us to understand past African societies as they understood themselves. Bennett uses the work of John Thornton as a synecdoche for a broader scholarly trend that insisted on recognizing, studying and describing the agency of Africans in the past, including in the making of the Atlantic world and the establishment of the slave trade. Bennett explains, I think accurately, that this imperative was driven by a desire to absolutely refute and reject the sort of histories that saw Dahomey or any other Atlantic African society as merely acted upon, merely the consequence of, a history whose causality and agency was fundamentally elsewhere. In this reading, the goal for Thornton and many other scholars (right into the present moment) is to restore to Africans in the past the fundamental human property of agency, the ability to act with intention, which in turn requires resituating the causes and development of the Atlantic world in African societies as much as any other. More generally, it requires trying to understand past African societies as they understood themselves, in their own terms, with a kind of presumption that the truth of what they were is not what they are now, what they were thought to be by colonizers in the early 20th Century, and not what the contemporary politics of race and class equity would think them to have been.

Which is, as I said, a recently-past presentist politics. It is the politics of social history and history “from below”. E.P. Thompson did not want to just put the working-class into history as something produced by industrial capitalism, as a kind of force of nature that had to be managed, confronted, domesticated, or gauged, but as human beings who fulfilled the oft-quoted statement made by Marx: “making history, if not in circumstances of their own choosing”. That was a political move as well as a philosophical, empirical and methodological one. It carried the weight of showing other historians that it could in fact be done and still satisfy the evidentiary standards of the historical guild. It required an argument about why it was important for historians and others to produce this knowledge, more important than the many other things that they might study. And it was motivated in part by a complex left-progressive shift in Western Europe and elsewhere that increasingly perceived the only hope of left politics lying in understanding people as they understood themselves, in working with and through consciousness (class, racial, gendered, sexual, or even individual). As the first generation or two of social historians often reminded their scholarly descendants later on, the senior historians of their day were under no illusions about the politics of social history, and often fought fiercely to keep it out of departments so that the really important things could still be studied as much as they should be: wars and battles, elections, the decisions and biographies of famous men, governments and great ideas.

The next layering of “studying people as they understood themselves” was a result of the rise of cultural history, the history of the “linguistic turn”. Historians who were broadly accepting of the priorities of social history began to realize nevertheless that if we needed to understand how people lived, thought, and inhabited particular pasts, we couldn’t use the sort of universals that social scientists frequently used (and still use) with abandon. Many historians became more and more idiographic, assuming that all past societies had a specificity that needed to be respected for reasons that were both empirical and political. Political because we were increasingly trying to show that same respect in our own social and cultural worlds, waking up to the fact that other people contained multitudes and intersections, but also to the fact that a kind of white male assumption about what was normatively “inside” of other people (psychologically, historically, culturally, etc.) was derived from white male subjectivity. To wake up to that truth in your own life as a human being (whether you did so as someone accustomed to use that frame to claim knowledge about others, or someone fighting against the use of that frame by others claiming to know you) meant you also had to rethink how you interpreted historical evidence, for empirical reasons. Once you recognized that the document you were looking at was written from a particular perspective, written in a particular genre, created for particular instrumental purposes, using a discourse that was profoundly intertextual, you weren’t just “subtracting bias” to find some positivist truth of how people used to act and think. You weren’t stripping away the distorting veil of language and rhetoric; language and rhetoric were the truth you were studying. You couldn’t understand “how people thought and experienced their own society in the past” from some disembodied, universal, view-from-nowhere way.

That was a politics too, and often hotly debated one, even within the left—a debate that has in fact not really ended. I recall an older social historian in a roundtable I was part of grumpily saying, “Why do we care about how people thought or felt? It’s a hugely disabling thing to get involved with, we should just study large-scale social formations and the material conditions they lived in, that’s the only thing that you can actually know and it’s the only thing that might be transformative in the present.”

Sweet in his own work wants us to know that the slave-trading rulers of Dahomey were challenged by political and religious dissidents within their own state and that those dissidents were acting on spiritual and ethical conceptions that were highly idiographically particular to their time and place. He wants to trace how that particularity transited into Brazil at a particular moment in the person of one individual who reconfigured his Dahomean consciousness and practices into a syncretic New World form. This is all fine—and I think well-supported by his research. But it has all the politics that I’ve described imbricated in it—the epistemological and disciplinary stew of the past forty years that has defined what historical scholarship should be.

And it has, in the form he’s chosen to enunciate in his AHA essay, something else that is, as the kids these days say in their latter-day Althusserian fashion, problematic. Which is to say this: what exactly is Sweet’s work warding off here, in light of the AHA essay? Is he warding off an Afro-Brazilian practicioner today who might read of Domingos Álvares and say, “I will add his practices as described into my own spiritual practices”? A Black artist who might be inspired by what he reads and incorporate elements into her work? A Black activist who might warn that folks have to be as wary of their own leaders as they are of dominant white-controlled institutions? How are any of those wrong in any sense? The almost-explicit point of the AHA essay is that all of those are secondary uses that depend upon historians to get it right in an expert way first, rather than for us to simply be part of the general tumult of people looking to make sense of Domingos Álvares or Dahomey, to make use of it, to understand it as it understood itself and to understand it as it has meaning to us.

I am fine with being part of the general tumult. And I do not like the politics of drawing sharp lines between the properly trained professionals and everybody else. I haven’t liked that since the first days of my graduate training, when my advisor opened my eyes to a really different way of understanding where historians are in a wider circulation of thoughts about and uses of the past. When you see that picture, you start to see kinship and connection where Sweet sees rivalry and danger. If, for example, the film “The Woman King” ends up representing the rulers of Dahomey as desperately trying to push back on or escape the trap of involvement in the Atlantic slave trade rather than as being agentive, willing and self-interested participants in it, then the film would hardly be at odds with the historiography of Dahomey. Properly trained professional scholars in that field have made the same argument, if sometimes about a different ruler or moment than the one the film is referencing. If the film takes a keen interest in the female soldiers of Dahomey, so too have properly trained professional scholars.

It is perfectly possible to imagine that many of Dahomey’s ruling elites might have—thinking in their own terms and in their own historical situation—been both agentively involved in the Atlantic slave trade and yet desperately wishing for a way out of it. That they might have seen themselves both as powerful agents in their own world and powerless to contend with the forces that surrounded them, whether that was the Oyo Empire or the merchants gathered in Ouidah. I would assert that we have some possible insight into that kind of trap in terms of our own hopeless entanglement with climate change. Is Joe Biden powerful or powerless to stop the production and consumption of fossil fuels? Well, both. Am I in the same trap? Are most of us? Yes, certainly. Where could I go or what could I do if I wanted to utterly escape the trap? It will go on without me even if I do. Some of us want to resist—as did the forebears of Domingos Álvares, in Sweet’s account—and we just as likely will lose. Some of our rulers may know that what we’re doing is catastrophe and yet see no way right now to change.

Is that a presentist analogy? Am I not paying proper court to the presumptive alterity of 18th and 19th Century Dahomey? What a precise configuration of alterity that is, then, understandable only if you put in the proper specific intellectual labor with the proper specific disciplinary training, and communicable only if a reader follows the precise unfolding of that labor’s fruits in a monograph. It’s a rather Goldilocks thing: on one side too presentist and untrained, and on the other side, an alterity so fiercely unknowable that it defies all possible labor or recuperation. (Hayden White is calling on line 1.)

To make the argument for the kind of work Sweet wants to prize requires owning the politics that produced what he blandly describes as an obvious intellectual priority. And, I think, a political thinking is needed to see how that work is not rivalrous to a general tumult of imaginings and deployments of history, that what is thought by heritage tourists in West Africa or filmmakers putting Dahomey on screen is thinking what we have also thought. That historical scholarship requires no specific configuration of a department of its own or an exclusive ownership of a way of seeing. That isn’t just political, it’s practical if you are (as I presume a president of a professional association would want to be) concerned with the survival of the profession. You want to be in the circulation, with humility and generosity, not trying to stand firmly apart from it.

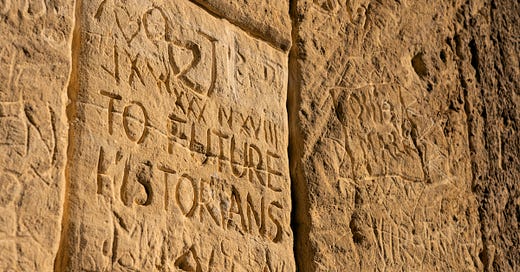

Image credit: Photo by Theo Aartsma on Unsplash

Excellent piece. Thank you. In an age when anything went and we didn't do "triggers" I chaired an exilarating Masters seminar on the the "pursuit of truth" by setting Polanyi against Chatwin's Viceroy of Ouidah. It was productive