Trump Essentials (5): It's The Gender, Stupid

Trump Has Cruelty and Malice For All, But It's Women That Are His Issue

Michelle Obama may not have gotten it right about going high when they go low, but she’s got it right when she says this election is about whether men—and for that matter, women—can take the lives of women seriously.

Since 2015, Trump supporters of all kinds have been reliably hot under the collar about the accusation that their underlying motive for supporting Trump is racial animus, that Trumpism is synonymous with white nationalism. You can read that reaction in any number of ways: a genuine exasperation with what they think is an inaccurate appraisal of their own motives, an anger at a perceived misjudgment of Trump himself, an overwrought defensiveness at a claim they privately know has some truth to it, a cynical deflection of a charge that they think is potentially wounding.

But I rarely see anything like that push-back when the charge is made that Trump is personally awful in his behavior towards women or that Trumpism wants to see a significant change in the status and role of women in American life. Trump supporters may loathe particular accusers against Trump like E. Jean Carroll, but most of them have accepted that their champion indulges in “locker-room talk” that they acknowledge is crass, that he has been serially unfaithful to his spouses, that he sees women through the prism of his own sexual desires and divides them into women he’d fuck and women he wouldn’t, that his reaction to women who criticize him is unmistakably misogynist. The supporters might contest whether he’s committed criminal sexual assault, but most of them know that the evidence that he’s been sexually aggressive for much of his life in an indiscriminate way is everywhere—including in his social proximity to Jeffrey Epstein. No one but the most fervid Trump cultist sees him as a model of chivalry, courtesy, or care towards women or for women.

Trump supporters may find it slightly embarrassing that their hero behaves as he does, but they forgive it easily because on the matter of women, they are themselves inclined to see the autonomy of women, the legal protection of women’s rights, the centrality of women to work and public life, as one of them major ways that America went wrong, as one of the things they want to fix in their pursuit of former greatness.

So many of the feeder streams into Trumpism well up from springs of reaction to changes in the status of women. Dobbs has made it plain that anti-abortion sentiment is primarily about control of women. Its supporters are indifferent to women dying, women risking death, women enduring pregnancy after rape. They are marching on unimpeded by the consequences of Dobbs to the next constraints to be placed on women’s bodies, the next opportunity to define women entirely in terms of reproduction. Vance’s disdain for “childless women”, the sudden vogue for natalism, all align in the same direction.

Most of Trumpism’s named villains in public life are women. The pronoun in “Lock her up!” was doing highly active work. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez not only produces apoplexy inside the world of Trumpism, but she typically haunts its zones of adjacency. She is the person that someone embarrassed by Trump’s excesses can still say might justify their vote for Trump: what if AOC became more powerful? Nancy Pelosi looms large in the MAGA imagination, whereas Steny Hoyer means nothing.

It’s not so much a matter of specific women, really, it’s women as workers, women as makers of meaning, women making their own decisions. Women not belonging to men, not being tethered to family. Women being people.

Here I am sure that many Trump devotees would insist that all that is an exaggeration: that they love and admire women, accept women’s independence, have daughters and wives. Or that they are women, and how dare I, a man, tell them how they think about womanhood.

To the last in particular, there’s a point there. This is an old problem when it comes to the inconvenience of women’s autonomy in the view of the American right. Anita Hill was attacked fiercely by other women. Some of the standout MAGA tribunes are women: Marjorie Taylor Greene, Lauren Boebert, Sarah Palin who actually are everything I just alleged Trump supporters disdain, and they’re in a venerable tradition that goes back to Phyllis Schlafly. The message there is substantially: do as I say, not as I do. The lesson there is also intersectionality, which doesn’t just mean “add up your oppressions to find out how oppressed you are”. It means that sometimes one form of social affiliation annexes another. Feeling a sense of belonging is also class, it’s region, it’s civic institutions, it’s hobbies. And so there are women who want the choices and lives of some other women to be circumscribed because they also want the social worlds, affiliations and forms of belonging those other women represent circumscribed, and not incidentally, one of the things they want circumscribed is how those women in those places living those lives behave and speak and seem.

Those women, and the men who try to take all women’s lives seriously, do not return that animus as a matter of policy or even as a front in the culture war. Nobody is out to ban being a tradwife or to pass a law requiring a woman to keep her own name if she gets married. The point with gender here is the point that the right keeps coming back to: that if they are not dominant, they are threatened. The churches can be full and the marriages lasting only if government and civil society align to make that as nearly compulsory as possible. Men can only be what they ought to be if women are made what they ought to be in relationship to manhood.

Manhood, it turns out, is the other reason that those women are the nightmare that wakes Trumpism in the night. There are all these earnest pieces coming out now from writers, more than a few of them women, who are worried about men, on behalf of men, in empathy to men. Worried about sons, worried about husbands, worried about brothers and fathers. What will become of them in a world where more women go to college, more women have better job prospects and increasingly close to equal pay, more women can tell men ‘no’ and have that stick? What happens when more women can live without men? Where more women might even have a chance of being President of the United States?

I agree that we’re in a genuinely disorienting moment when it comes to thinking about gender. For all that some younger people have a term for gender being mutable, fluid, even performative—genderfluid—at least some of those same people seem at times to be distressingly certain that any given individual’s gender has a natural and essential foundation. Sometimes that person doesn’t know it yet, and the hope is always that they will—and that in some sense even being genderfluid is a fixed kind of fluidity.

For any number of people my age, this view isn’t the progressive mindset we worked to achieve under a different historical dispensation. You get a hint of this in Judith Butler’s recent acknowledgement that her earlier rendition of gender as performative and mutable has crashed headlong into a more generationally recent kind of polycentric essentialism—that there are many genders but all of them have a kind of foundational rooting in what a particular person is meant to be.

Yet I can work with that, and it helps me think a little about what is wrong and what is right with this newfound worrying about the future of manhood. I do feel I’m a man. Whether you think of your own sense of gender as fluid or relatively fixed, you nevertheless think it. You feel it, it shapes who you are and what you do. And it is in fact frustrating, irritating, even depressing to feel that those feelings are subject to constant negation, that are never affirmed or embraced. (Women reading this are like: take a number and get in line, buddy.) In my own case, as a person who feels himself to be male, there are aspects of my gendered selfhood, of “traditional” masculinity as a way of being, that I like. Some of those concepts or feelings are sometimes seen as a problem that men have: a desire to be reserved or withhold, an attempt to be stoical about pain, a desire to control your emotions, a wish to protect loved ones, a sense that honor and duty matter. It’s certainly true that all of these feelings, these ideas about how to be, curdle frequently into self-harm or into violence against others, and it’s also true that when they are admirably felt and expressed, they belong to and are located inside femininity as much as masculinity.

I’m doing my best here to be nice and say that when someone says they have sympathy for men who are wondering what their role in the world will be, about how to act as men, about what kinds of archetypes or norms are ok, well, thank you for the sympathy. Thank you especially for younger men, who may in fact feel lost.

But also, seriously, when this sympathy starts to wander off and look enviously over at Trumplandia and say, “Why, it seems our young men are finding a home there! Maybe they have some meaning to offer our wayward men!”, I call bullshit.

Because what Trump has to offer men is permission to hate women. Those women.

And the terms of that hate are not “Women are taking away our precious cultural ideas about manhood!”. It’s pretty much “Women are taking our jobs and our social power, women are doing better at most of what we have done, women are—without any malice or plan—unveiling the many cases where men have risen to the top on nothing more than mediocrity and a pair of testicles. That’s what women are doing. Those women.”

A fair amount of the time, culture war is culture war: it’s about ideas, feelings, expression, imagination. Not this time: the counter-revolution here is not about women (and male allies) who are discrediting “traditional manhood”, it’s about some people fighting to reverse two generations of redistribution.

We’re not going back, indeed. The reaction to Dobbs is but a hint of what might be to come when those people fight back. A victorious Trump might move to deport a million vulnerable people and succeed, but I have to hope that when—not if—he moves on all those women, he will fail again, as he admits he once did. That he can’t get there, and never will.

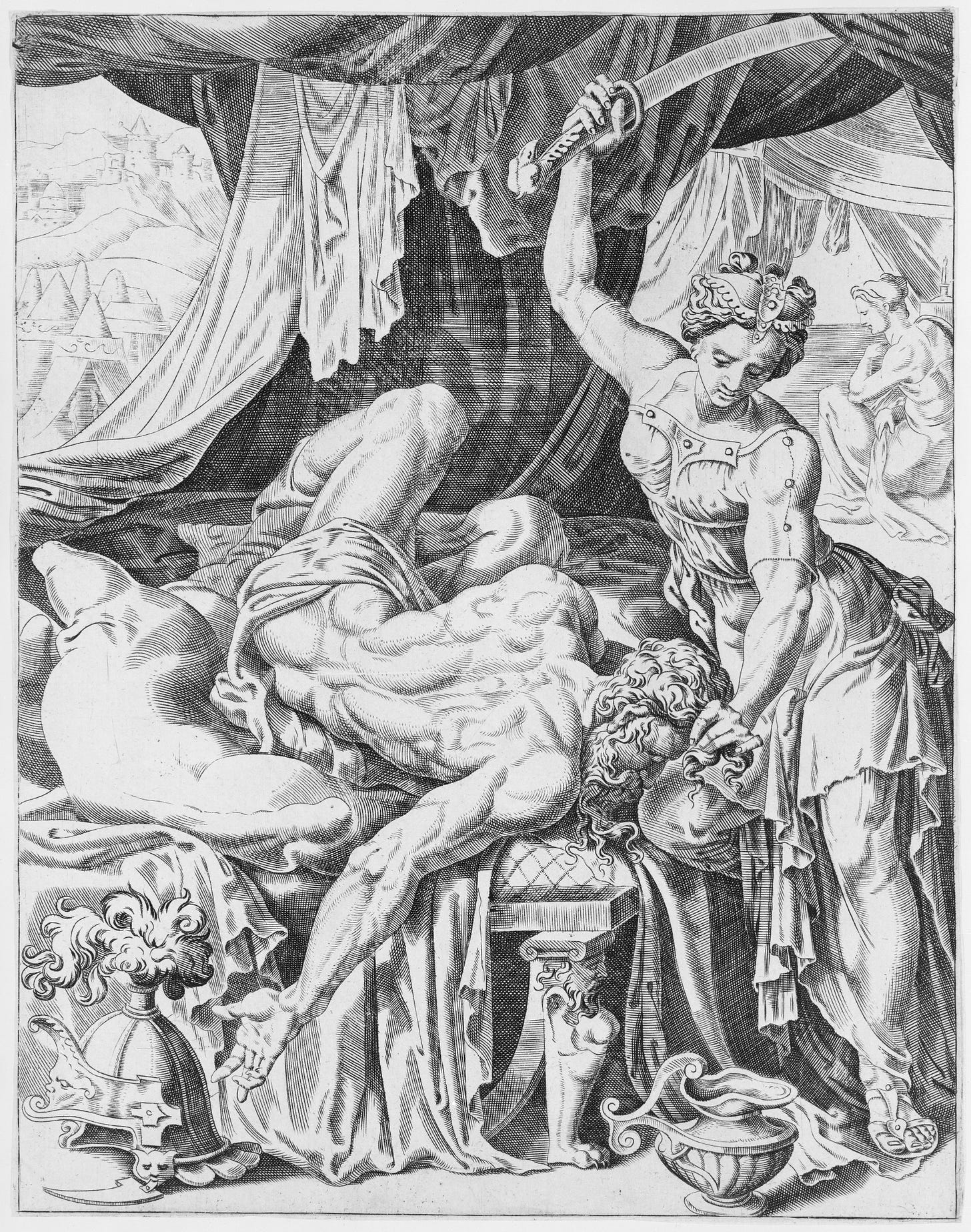

Image credit: Dirck Coornhert, “Judith Slaying Holofernes”, 1551. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Thank you. I've been saying for sometime to anyone who will listen that much of contemporary discourse about gender—and indeed, identity politics in general—seems to start from a premise of social construction and then make a weird turn into essentialism and proceeds as if there is no contradiction here.