How’d the weekend go? I made some very Superbowl food and we watched part of the game (the last quarter and the OT). We also watched “The Marvels”, which was much worse than I expected.

The Internet has moved on to talking about whether the Illuminati Defense Secretary Taylor Swift orchestrated the Chiefs’ victory and doubtless by this afternoon will have a new obsession. I’m still stuck thinking about whether Joe Biden is too old to be President.

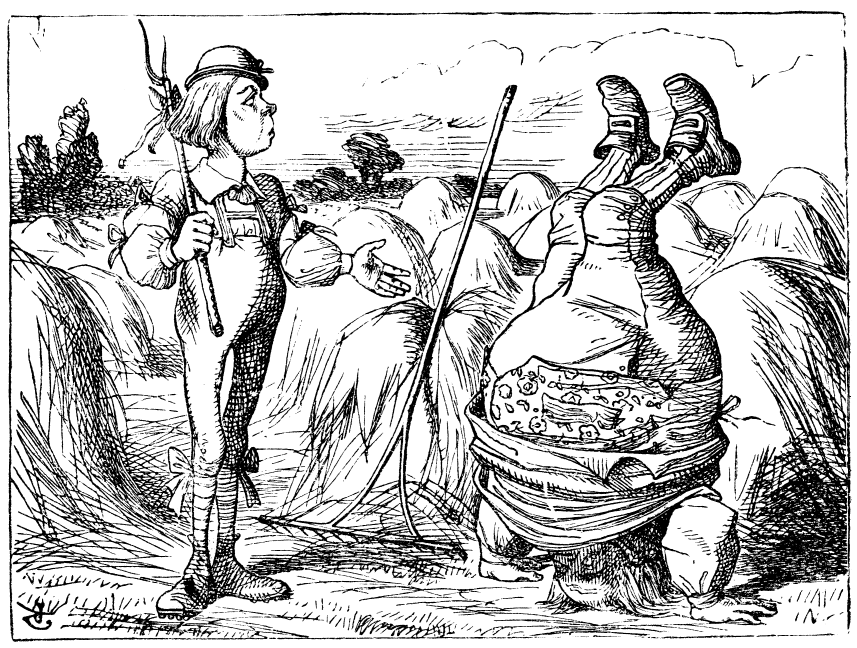

“I have answered three questions, and that is enough!”, says Father William in Lewis Carroll’s poem.

A line which captures the mood in the wagons being circled around President Biden.

Which in turn has generated a pile of digital finger-wagging about age, capability, expert evaluation, the hypocrisy of the press, and the unprofessional hackery of Special Counsel Robert Hur.

All of that chatter seems perfectly cogent to me, taken in isolation. Yes, some people in their eighties are perfectly competent. Yes, mixing up the names of two world leaders is not a big deal. (If it were, the Other Guy would be a much bigger deal than Biden, which he is anyway.) Yes, the press, especially the New York Times, are being predictably self-righteously stupid in their following of a horse-race script while trying to pre-emptively kiss up to power wherever it may end up residing. (If America descends into fascism and then one day comes out the other side, mainstream American journalism will at that future time definitely be accounted as one of the enablers of that descent into hell.) Yes, Hur went way beyond his remit, though the buck for that one stops at the desk of Merrick Garland, a terrible Attorney General at a time that absolutely required the best.

And yet, across social media and public culture, all of that chatter also seems too much in an already rather familiar way. It feels defensive and pre-emptive. In many places I frequent, even the slightest utterance of the sentiment “Biden seems old and frail” produces an almost instantaneous reactive wave of replies that amount to “He’s not and it doesn’t matter if he is and he’s been great and SHUT UP, you’re going to lose us the election, you traitor”.

That reaction says something far more than it means to say, and what it says has little to do with Biden or his age in specific.

It’s a common observation that the Democrats have been in a defensive crouch at least since 1998, arguably since 1968, offering as the single meaningful plank of their party platform, “Stop the other guys from winning, because when they win, really bad things will happen.” Since this claim is absolutely true, and has been more intensely true since 1998, this has sometimes been enough for them to eke out electoral majorities in Congressional districts, Senate races and Presidential elections.

Sometimes it hasn’t been. The debate about Biden’s age is essentially a recurrent debate about all Democratic Presidential candidates since 1976. With the lone exception of Barack Obama, the party has nominated a string of uncharismatic, relatively unappealing standard-bearers whose political vision is an assembly of carefully crafted advertising slogans, calculated pandering, and technowonky incrementalism. Even Obama is really not an exception in the sense that his charisma and personal decency, which were quite genuine, lay on top of that exact same political vision.

The central structures of the Democratic Party are devoted to two propositions which also rule the larger organizations predominant in white-collar and professional life across the United States: that merit should govern the entry and initial ascension of an individual within an organization and that seniority should function as the equity-based counterweight to merit. Merit is the pupal form; seniority the butterfly. Merit is what makes the variance between individual compensation and perquisites fair or moral; seniority is the incentive that rewards everyone evenly for long-term commitment to organizational mission. This culture extends beyond workplaces and shapes the entirety of the social world of people who hold to some form of it.

Beyond the world where those principles are still (mostly) shaping outcomes, there are prowling oligarchic billionaires who loathe that work/life culture, because it often functions as a kind of modestly annoying restraint, a sort of home-arrest ankle bracelet, whenever they have to interact with their large corporations, serve on university or civic governing boards or deal with the few remaining tatters of an older regulatory order and public sphere. There are people who own small but profitable businesses, people who work in older paradigms of office labor in public and private workplaces, people whose working lives are wholly outside of the merit/seniority progression and its intrusion into the whole of life. All of whom are unsympathetic or incomprehending. Young people living in the gig economy, with its ceaseless instability and commandment to self-promote, look on the stolid uncharisma of the leadership that the merit/seniority world produces with impatience and frustration.

“Biden’s too old” is just the particular semantic reformulation of recurrent misgivings about that uncharisma. Hillary Clinton’s too distant, bureaucratic and synthetic (and yes, female); John Kerry’s too programmed, cerebral, and uninspiring; Al Gore’s too cold, methodical and calculating; Bill Clinton’s too sleazy, patronizing and sexually predatory; Mike Dukakis is too geeky, intellectual and unfeeling. The central controlling synonyms down at the bottom of the word tree are essentially: too professional, too inauthentic, too remote. Too much like people who’ve climbed up the ranks with no profound sense of vision of what a society should be. Whose answer to “what politics should we have?” is “well, what politics will get me the job?”

Our organizational worlds spill over with missions and mission statements, with visions, but none of them really uncover the driving values and sensibilities underneath. They don’t come from the same place or reflect a consistent aspiration. They are adopted as post-facto descriptions of what an organization already is and with the plain intention to lightly validate the existing commitments without providing any guarantee of their continuance, any assertion of their rootedness. Projects, proposals, policies are all enunciated first and foremost because they can be done by someone now present within the organization. Believing that there is a need to do something where the method or program for doing it is not yet known or specified is something you don’t do, because why would you? Nobody gets a merit reward for stridently insisting on a vision that can’t be assigned, and nobody climbs to seniority constantly infusing a deep idea into the bones and blood of the organization, because that’s not an item that goes on a resume. It’s all about the deliverables. The small ones, a capacious grab-bag full of them, none of them sharing the same underlying ideas or aspirations.

The Democratic Party wins elections because the opposing party and the social coalition behind it is a mortal threat to everyone else in the country (and many outside of it). And with a smaller core of its voting base, the Democratic Party wins because of the familiarity of its merit/seniority structure, the regularity of the conveyor belts that move the bright lights of yesteryear along, molding those who made a splash when they came into politics— bristling over with the resumes of Rhodes scholars, antiwar activists who also served in the military, authors of pivotal legislation, governors of states, reliable Senators—into the inevitable leaders whose time has come.

It is that core constituency that furiously excoriates the disloyal complaints of peers who hunger for a deep vision of where we’ve been and where we want to go, that primly corrects critiques about the plainly uninspiring candidates who line up one after the other to claim their anointed prize. No, he’s not too old; no, she’s not remote nor centrist and you’re sexist for thinking it so; no, it’s perfectly right that he should leave behind his inspiring history as an antiwar candidate; no, it’s normal that he should distance himself from the administration he served as vice-president; no, there isn’t anything sleazy, calculating or sexually unethical about him. No, no, no. The tank picture was a set-up job, the special counsel is a plant, the swiftboating is psy-ops.

Much of that response is true enough in its particulars, but it also betrays who the Democratic Party and its most devoted base is talking to in those moments: other organizational people who daily make peace with the uninspiring leaders that slowly push their working lives in a dung-beetle trudge towards small missions and disparate goals. The excuses, the acceptance, the resignation are familiar and portable; the explanation that it’s this or the howling chaos of a society falling apart at the seams and the ransacking promised by various barbarians at the gate holds true wherever they look. We are everywhere reconciled to uncharisma, everywhere told that we live in an age too sophisticated and grown-up to expect something like a vision to direct us.

But this also means a Democratic Party which is functionally incapable of processing the wider signals it gets from a bigger world of people who look to it not only for protection from an ever-intensifying menace but for a comprehensible, inspiring vision of what might be. The Democrats still don’t understand—Obama plainly doesn’t understand—why “hope and change”, spoken from the mouth of a man who seemed to embody both—provided them their safest electoral harbor in a lifetime of stormy wreckage. When your inside voice is very loud, you can drown out any unfortunate resident of the same home who says the bad things about the uncharisma of the pater/materfamilias. But many otherwise friendly neighbors still walk to and fro wondering why the house is in disorder, uncowed by the shouting.

This is not a matter of needing to “have a deeper bench”, of doing a better job of attracting merit at the intake or a better job of moving the right people up through seniority. This is a question of how deep social structures inflect into political parties and movements, in ways that are hard to change even if you have some degree of tactical insight into your difficulties. Those changes tend to happen only when that inflection becomes incapacitation, when it becomes lethal inbreeding, when the social structure and the political party arrive at a point of acute crisis.

In the case of the Democratic Party of the United States of America, there’s a reasonable chance that this moment will be November 2024. I pray it isn’t so, but I also pray that if somehow the argument that “we are the only protection against the chaos beyond” once again wins the day for its uncharismatic bannermen, that somehow the nearness of that disaster will finally lead to a full and fundamental transformation of the party’s entire character—and of the mirroring organizational worlds that surround it.

What would you say to the young people who have become horribly disillusioned with the democratic party, especially since Bernie lost in 2020? Sander's presidential run in 2020 in the democratic primary united a wide swath of the left behind him, from normal democrats to the DSA to more radical groups like Socialist Alternative. With his loss, the left has really fractured and even recent heroes of the left like AOC and even Sanders himself are now seen by many (but certainly not all) of the most energized sections of the left as establishment figures, not much better then Biden. The US-supported violence in Israel and Palestine has brought this dissatisfaction/disillusionment with dems into sharp relief and I think has pushed many people who simply felt unenthusiastic about the democrats into outright hostility. I've seen this vocally expressed at many demonstrations for a ceasefire in Gaza. I think what makes all of this especially difficult is that there is no clear path forward. Calls for an independent third party for the working class, a massive logistical undertaking, are common on the far left. However in 2024 the various left formations (the Green Party, Party of Socialism and Liberation, the academic left as personified by Cornell West etc) could not even coalesce around one presidential candidate. At the same time, leading figures of the DSA have all chosen to endorse biden. The hand the threat of trump seems very real, at the same time the spectre of fascism seems already to be growing under the democratic party as in Atlanta with the "cop city" affair. What worries me even more then a trump victory (terrifying as it is) is that I can't imagine a viable way for a third party to emerge that would be backed by the traditional supporters of the democratic party (who are the constituency the left wants to represent) and the elements of the left that reject the democratic party. If Trump wins this year and the democratic party collapses, as some see as inevitable and even desirable, I don't see how a new third party would emerge that would not have the same divides as the democratic party and the radical left currently have.