A Wrong That Makes the Right: The Iron Law of Power (2)

The TLDR Would Be: This Will All End Badly, And We Know That Already

In the first of this series of essays, I mused about the global right’s relationship to history and “heritage”, which has been a consistent driver of fascism and ethnonationalism for the last century. (Authoritarianism more broadly isn’t necessarily obsessed with blood-and-soil ideas of belonging—authoritarians are just as prone to coming from small ethnic and religious minorities that are in no position to work from that premise.)

In this essay, I’m moving on to another sprawling territory of far-right thought that is now tragically in the ascendance after a long era of marginalization. Like “heritage”, the ideas and beliefs in this domain are in fact coherent and consistent propositions about human life.

Stephen Miller, one of the key planners driving Trumpism, articulates this view succinctly today in validating a desire to seize Greenland by force and make it an American possession: “We live in a world, in the real world…that is governed by strength, that is governed by force, that is governed by power…these are the iron laws of the world since the beginning of time”.

In this moment, Miller starkly rejects an equally coherent and consistent moral and political order that has arisen in response to human suffering both recent and ancient.

He rejects the vision that shaped the post-1945 world, the conclusions teached by ordinary soldiers and national leaders, by preachers and poets, by the survivors of genocide and the remorseful publics that vowed never again. In that moment in the ruins of World War II, people concluded that not only was war by industrialized mass armies armed with catastrophically powerful munitions an evil that could end all of humanity, but that unchecked aggression by nations and leaders who worshipped the “iron law of the world” and arrogated to themselves the right to murder millions within their own borders was the cause of that great evil.

He rejects the moral awakening of the world to the harms of imperial overrule based in racial hierarchy and unearned civilizational arrogance, to the bitter outcomes of unashamed plunder and theft. He rejects the hard lessons learned by Europeans in centuries of war between absolutist states and rival religious factions in which ordinary people were frequently put to the sword or burned alive, famine and plagues went unchecked, and prosperity was squandered.

He spits on the New Testament and the Ten Commandments, themselves products of hard-earned lessons about right and wrong if also for believers the instructions of God to the human race.

But Stephen Miller is in his way correct. That force is alive in the world, that it is the only real thing behind laws and norms, behind systems and institutions, behind right and wrong.

While I am no fan of the idea that “right” and “left” are a “horseshoe”, two ends of a mirrored deviation from the proprieties of a “center”, it is true that in his declaration, Miller is curiously echoing the central insight of critical race theory as well as many other left-associated ideas such as Giorgio Agamben’s “sovereign exception”—that laws, regulations, and moral commandments that seem to restrain force and provide a basis for consistent justice are just veneers that disguise (and sanctify) the use of violent power to maintain a fundamentally unjust order.

The difference is critical, however: the left that argues thus is saying that this is a bad thing. Critical race theory is not embracing a world where might makes right, it is simply saying that the laws we have don’t do what our ideological claims about them say they do, that the rights we identify are not honored or upheld with the consistency and persistence that we ascribe to ourselves.

Miller is saying that the iron law not only exists, but should exist. That it is the way the world is and the way it ought to be. That the only thing in life is to amass as much power as possible and to use it as capaciously as possible, and that if you fail to do so, you will be the victim of power, not its wielder. That the golden rule is not “do unto others as you would have them do unto you” but “do it first to others so they can never do it to you, do it all the time with ceaseless aggression. Grind the world under your boot or you will be ground.”

This is where Miller and his compatriots strike a chord with many other people, and not just Americans. Moreover, though I think more by coincidence than perspicaciousness, they are striking at a vast space of intellectual and practical absence in the heart of the Western left that leaves it in disarray when facing an open embrace of the “iron law of power”.

Let us talk first of the chord that Miller strikes, which rings loud all the way down to the intimacies of family, household and local community. In fact, rings loudest in those worlds. If it seems to explain the incomprehensibly complex and large-scale action of nations, corporations, markets as well, I think that is because people extrapolate from the way they see force, compulsion and purposeful violence in their own lives.

The first thing to realize is that when a young idealist shows up to tell people that they are living on stolen land, that they are the beneficiaries of centuries of enslavement, that they have racial privilege, they often act as if they are revealing a surprising plot twist to an audience that never saw it coming, and they are in that belief exactly incorrect. Many people already know this extremely well, and they don’t have to be white men to see it. Most people know that what they have, they have only by right of current possession, and that they are one bad day away from having it taken from them. Taken by natural catastrophe, taken by sudden illness. Taken by a loss of employment, taken by the mysterious and ineffable complexities of regulation and government, taken by the uncontrollable withdrawal of the market’s favor. And they know often that they have what they have by the force of accident or coincidence: a lucky job offer, a conniving friend or family member who has arranged an opportunity, an inheritance from a relative whose favor is barely earned or justified. From being the lucky one who bought a few bitcoins or IBM at the right time, from owning a little bungalow house in 1965 in Southern California.

And yes, I think people know, at various levels of consciousness and immediacy, that if they have something, they have it at the expense of others. That is the foundation of everyday racism and discrimination. A knowledge that the people in the poor neighborhoods didn’t get there by accident nor by natural justice. In many cases in 2025, parents must look at children whose future prospects are limited and know that on some quite concrete level that this is partly the fault of the parents and the grandparents. An old Teamster with a grandson who drives a truck has to know somehow that the Teamsters squandered the future a long time ago. A parent who chose a bourgeois profession who could have gone into finance or consulting has to know that they chose respectability over money and it’s the end of the line for respectability. But the more abstract understanding shivers in the bones, too: in the names of places given by Native Americans who are no longer here, in the dead bones of Black neighborhoods paved over by interstate highways and the Reconstruction-era farms of former slaves that were transferred bit by bit to white muncipalities and white owners, in the faces of undocumented workers in dairy farms and meat-packing plants. What you have today you might not have tomorrow if things were set right, or so you fear. You cannot trust that things could be set right so that everyone keeps what they have and everyone who deserves more receives it.

It’s a deeper thing in the heart for many, I think, and here especially it is men who have that feeling. That they are in some sense unworthy of what they hold and unwilling to earn it. They know they should do more work around the house. That they’ve wasted money and missed chances. That they’ve cheated on a partner, or not cherished them. That they’ve not lived up to their responsibilities. And so not only does life feel like it could slip away for reasons beyond the scope or understanding of any person, it feels like it could flow out of grasp for reasons all too known.

The iron law of power seems like one solution to all of that. Defend what you have against all dangers both real and imagined. Use commands, turn to compulsion, where persuasion and empathy might prove too hard and too fragile. If one wife slips away because you can’t force her to stay on your terms, find another. Sift the world for weakness and vulnerability and convince yourself when you find it that you have affirmed your own ascendant strength. Inscribe your boundaries and patrol them relentlessly, and enlist your family and neighbors in a network of mutually aligned declarations of force. That’s not just men, either. Women, especially women who assert authority over and within households, can embrace the solution of the iron law of power, that under their roof, all will be as they command it to be.

It’s not all interiority and sentiment, either. The world provides some empirical validation of the iron law of power in the everyday world of liberal capitalist modernity. It’s precisely why two generations of American parents have held their children so close in many cases—a sense that the world is full of predators and that many of them hide behind laws and codes and respectability—teachers, priests, coaches, celebrities, civic leaders. It does little good to point out that this sense is exaggerated in actuarial terms, that the probabilities are lower than they seem. The point is that there is a sense that others are acting by the iron law of power without admitting it, and that the only defense against such misdirection is to lose your own vulnerability and exposure.

Think about it: every day all of us withstand forms of violence seeking to reach inside our lives. We have learned to shrug it off, to guard against it, because it is so disorienting to dwell on the avalanche of attempted financial scams, the possibility that a simple comment on social media might bring the hostile scrutiny of thousands of strangers, the fear that a new neighbor might suddenly build a fence over the property line or report you to the HOA. Women walk the world knowing that at any moment, a man can grab their bodies, demand a smile, steal an opportunity, unloose a devastating but deniable attack on their confidence. A Black person knows they are always one moment away from a cop pulling them over for nothing or being shot by someone invoking “castle doctrine”, a doctrine which is merely a subclause of the iron law of power.

And empirically even people who don’t see the world that way intimately do despair of the empty vapidities of other ways of imagining our shared lives, particularly of the vision of more-or-less liberalism. Somebody oughta do something is a precursor to the iron law of power as surely as “We the People” opens the Preamble, and there are situations where there’s no other voice that is remotely persuasive or confident to turn to. What do we do about someone whose mental health crisis is leading to self-harm but threatening harm against others? What do we do about assholes when the “no asshole” rule fails us, or about pervasive sexual misconduct from people who masterfully understand how to avoid detection and subvert the rules? What do you do if you have a drug addict in the family who steals, cheats and harms family members? In the grander sense, what do you do about people who use power and wealth to ignore the laws and break the rules with impunity? About companies that throw away whole communities like a half-eaten fruit?

The iron law of power beckons for all these questions, even for people who live a different sort of moral life full of dialogue, compromise and mutuality in their most intimate worlds. It provides a meaningful answer, even if it is often not the answer we want, because sometimes what it says is, “You don’t have the strength or the power to defeat your adversaries, so accept things the way they are. You are the face under the boot, not the boot itself.” But the iron law of power, if you steer by it, at least says also, “And if you get the chance, if they give you even a slight opening, you grab that foot, you throw them down, and you show them what it’s like to be under the boot. If you get that chance, never let them up.”

It’s an enticing promise that threads through revolution and reaction alike, that tempts us by promising that the iron law of power could be righteous if it was only us doing it. We in fact threaten this all the time in our invocations of sociological wisdom, that a dream deferred through the violent action of the iron law of power will explode, not just fester. And it is what drives devotion to the iron law of power in some—a belief that if they let up for even a moment, they will be ground down in turn, which is then a self-reinforcing loop. The more that they use force to keep their enemies real and imagined in line, the more they seem to guarantee a Newtonian violence, an equal and opposite reaction in turn.

Here is where the void of opposition to the iron law is at its vastest extent.

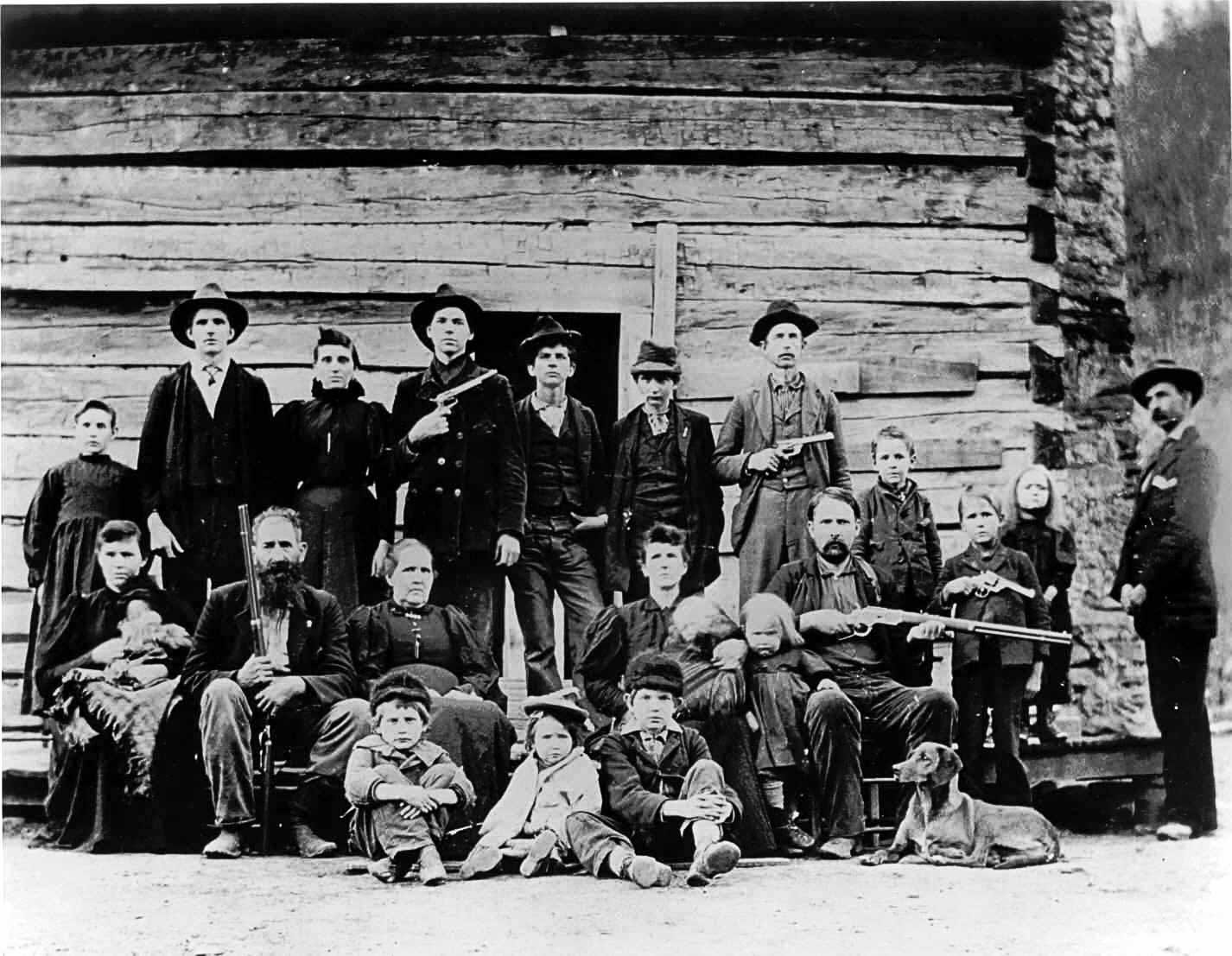

Those of us who reject the iron law of power can with some empirical and philosophical confidence say that it proposes a hideous cycle, an anti-hedonic treadmill, that makes the whole of human life nothing more than an endless blood feud of force and retribution for force, Hatfields and McCoys all the way down. There are so many real examples in history of societies and communities and institutions caught up in endless cycles of violation and reprisal that ended up with everyone desperately searching for a way out. You can prove it with Prisoner’s Dilemma, you can show it in psychology.

You can equally prove the impermanence of the strength that makes Stephen Miller confident that the iron law of power is on his side. The iron law of power has two iron corollaries. The more dependent you are on the iron law of power, the more you will have to use it crudely and disproportionately to achieve all desired ends, and the more you will force all other parties to summon all their strength to counter your actions. Someone who lives by the iron law of power inevitably—and often rapidly—dies by it. At the very least, they bequeath to any heirs an unsustainable situation. It is why and how empires fail: they are forced to extend their power into their frontiers, which stretches and disperses their available strength and makes them vulnerable to powers beyond their frontiers. They then have to draw more strength from their core, which depletes their resources and hollows out their power.

In the harsh light of reality, the iron law of power is only genuinely appealing to nihilists who want everything to crash down or to people so unabashedly narcissistic that they don’t particularly care what happens to those they leave behind It may be that Miller and his compatriots fit both of those descriptions, but I think at the more intimate scales where strength, force and violence tempt people, this bleak reality may push against that temptation.

The problem is that most of us who reject the iron law of power do so from a moral intuition that goes beyond the inevitable failure of strength and force, out of a belief that everybody can get what they want and need from one another through mutuality, persuasion, solidarity, and kindness. That the social contract can be the kind of deal where everybody wins.

The problem for those of us who so intuit is two-fold. First, we don’t have much to say about circumstances both intimate and vast where plainly this is not the way it is even if we wish that someday it could be. This is often where we bring law, regulation, rules and some kind of sovereign authority into the picture and remand the situations we can’t solve through love and mutuality to what we hope or believe to be the democratically and mutually sanctified power of law, of customary practice, of institutional regulation. And most of us know that’s kind of bullshit in one way or another—that there is a huge circuit breaker between associative life and the laws and codes we turn to where associative life falls short. When our bullshit gets called, many of us have weak or evasive answers.

More importantly, we use rhetoric in associative life, in persuasion, that invokes commandment and compulsion in order to avoid its inevitably mutualistic predicate.

I know I turn to this anecdote a fair amount in my public writing, but it has stayed with me in a very deep way. More than a decade ago, I found myself joining an effort at community-wide reconciliation at my workplace after months of protests over various injustices. We were seated at tables that mixed faculty, staff and students. At my table, there were two students whom I knew but hadn’t taught who were insistently pushing forward the line that historically dominant groups within the community must surrender their privileges. Something about the insistence was so lacking in critical thinking, in self-awareness, that I got the bit between my teeth and really came back at them. “Why,” I asked, “should people who have privilege surrender it? Isn’t it in their interest to fight as hard as possible to retain it? What can you offer the privileged that would convince them to voluntarily surrender its advantages?” This baffled the students for a while: they continued to insist that there must be a surrender. I asked, “Do you envision having the power to force them to do that?” No, they said, though I think they hovered uncertainly between “that’s not realistic” and “that’s not morally right” in that “no”.

That is actually the moment where you have to decide whether you’re following the iron law of power or not. You can follow it and judge that you don’t have the power to force or compel what you demand, at which point you’re involved in something like a con game where you’re hoping to trick some vulnerable dummies into giving up what you can’t take from them. This is precisely what some on the alt-right argue that the “woke” left has been doing for the last decade or so, and there’s at least a sliver of truth to it. But you could do what the students I was talking to eventually did, which is realize that they didn’t mean must, they meant ought to, and they meant ought to because they believed that someone with privilege ought to have compassion for those who do not and ought to desire a world where human life is not a zero-sum redistribution of a fixed amount of privilege through force and violence.

Which to my way of thinking is the right conclusion. The void is that we lack a theory of compassion, of solidarity, of mutual recognition, in terms of how they come to be, of how they become something so commandingly felt and lived that they cannot be alienated from our subjectivity, of how it happens—because it does happen—that the world is ordered from its most intimate to its most abstract—by this different kind of principle. We leave this sort of thinking to spiritual traditions or to faintly insincere and sickly-sweet sentimentalities. To empty invocations of peace. To people who profess mutual openness while dispensing cruelty and subterfuge, or people who demand compassion while offering none.

I think a proper theory of compassion, of its supportive laws, might see it just as much as a practical, empirical and concrete principle, visible in the ways we consider reciprocity—including the danger of reciprocal violence or appropriation—and withhold ourselves from doing what we could do. I think we could see it in fugitivity, in restraint, in deliberate absence, while also seeing it in generosity, in exuberance, in excess and abandon. The supportive law of compassion is with us on dance floors, in sitting shiva, in aid to strangers, in the spontaneous joy of small creativities, in the work we do not have to do but give ourselves to nevertheless.

It may be enough to point out where the iron law of power has lead us all so many times, because most people have seen enough of how it goes wrong in households and neighborhoods, between lovers and friends, to know that it is a fatal temptation. Even those who fashion themselves as strong may be able to hear the small voice that warns them of the weakness that awaits. But I think we need a better and more vividly inhabited call to the velvet law of compassion to really think our way into a fully realized counter to Stephen Miller—one that concedes that force remains a possible and plausible answer to the problems that we have no other answer to, that concedes that we live under the shadow of the iron law even when we wish to walk in the sun.

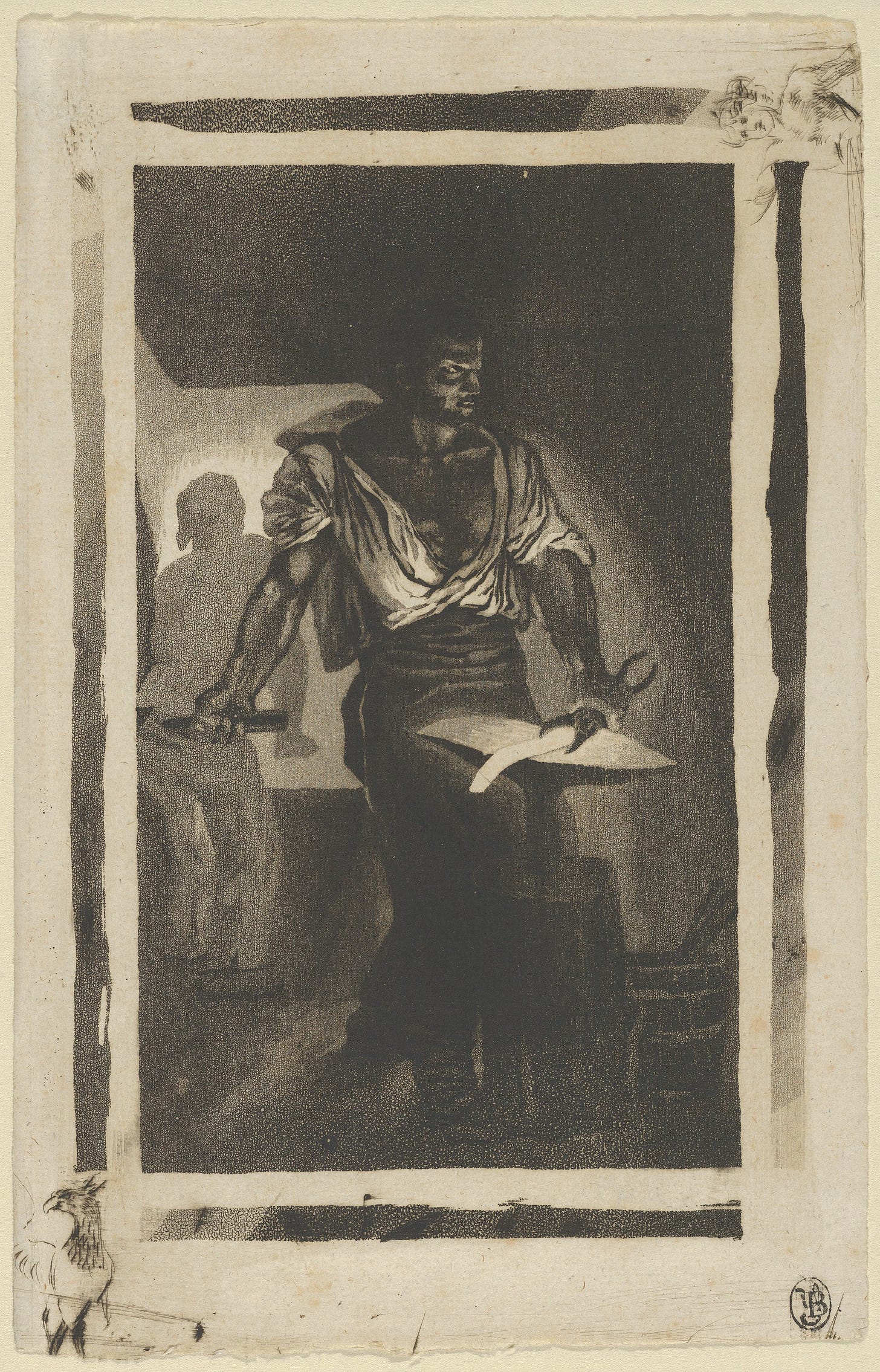

Image credit: Eugene Delacroiz, A Blacksmith, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/336629

Image credit: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=632843

“But Stephen Miller is in his way correct. That force is alive in the world, that it is the only real thing behind laws and norms, behind systems and institutions, behind right and wrong.”

Thank you for saying so well what underlies our current moment!