I was thinking about AI and writing again today, perhaps kicked off by a NYT piece that kind of annoyed me about Sam Bankman-Fried, “effective altruism” and “AI safety”. But I also noted over the last few days a recurrence of increasingly common discussions about the future of writing in college courses in several social media platforms I read.

I have some simple answers to the question of what faculty who use writing as a tool of assessment should do, and they’re the same answers I give whether or not AI is part of the conversation. Following John Warner, I think the basic problem is with the use of writing as a tool for measuring content mastery rather than using it as an expressive medium that is valuable for and of itself. The only reason increasingly capable AI writing is forcing that issue is that there will very soon be absolutely no way to tell whether a person wrote something that demonstrates knowledge of content unless it’s done live while you watch the writer do it. I’m sure some people are going to try just that, which will create a new demand for invasive anti-cheating surveillance, because big universities aren’t going to give up teaching people in groups of 500, 1000 or more where putting individual eyes on every single writer is impossible. I don’t underestimate the stubbornness of faculty and management about keeping a particular kind of Rube Goldberg machine running, despite all the sloganeering about adaptability and flexibility. (Those words really only mean “firing people” and “outsourcing services”, for the most part.)

It’s a losing struggle but not just because writing is a lousy way to assess command over content. It’s also a losing struggle because of how antiquated our sense of why people need to know how to write has become, is becoming, irrelevant as I write these words. Many professors and most institutions of higher learning have deeply accepted that writing is universally useful and necessary, and in particular, that it will always have a huge pay-off in any form of white-collar labor. This has always been debatable: bad writers abound in middle and upper management in most professions and businesses. Bad writing is one of the essential reasons that some middle managers have to “manage up”—they become an amanuensis for the boss, the polisher of memos, toasts and communiques. It’s one of the pervasive dissatisfactions of those bosses who are skilled communicators, that the new hires, even from the fancy schools, can’t write worth a damn.

But the vast torrents of routine communication that course through most large organizations are imminently going to be something that an AI can write as well as well-paid employees can write. Need to write a sympathetic message from the CEO about current events? Just input “sympathetic message about recent hurricane from John Smith to employees” and voila! you can fire your crisis communication specialist. Need to send out a memo reminding people about the cover sheets on the TPS reports? Telling people that you need them to be hardcore and to commit more to building the 2.0 version of your company? Inviting people to participate in a visioning exercise? You name it: it’s going to be AI written and you’ll never know the difference, if you happened to be alive in the age when meat-people wrote as if they were generic robots. I’m underselling what the capabilities are going to be. I think you’ll be able to tell the AI “Write a sympathetic message from the president about George Floyd with some personal warmth and a relevant quotation from a famous American author” and get exactly what you asked for.

This poses at least two dangers to the remaining human beings who will be working in those future organizations: first, that they’ll be inundated with six or seven times the volume of written communications once it’s easy to compose them (we’ll probably have automated calendars prompting the AI writers without a human being in the loop at all) and that the flesh-and-blood people exposed to that flood of writing will also be receiving deceptive communications that aren’t from who they purport to be or were not authorized to say what they say.

Some of this is going to extend upwards into forms of communication that we think of as being more difficult and bespoke. A fair amount of STEM scholarship is going to be something that you could arguably tell an AI to write as long as you give it the data, the charts, the methodology section, etc. Which is in turn going to make predatory publishing much, much, much more simple to do, while also giving the for-profit publishers an even more ridiculously extractive grip over scholarship by making them the only people willing to spend at least a bit of money putting real human eyes on the heaps of scholarship they’re charging us to look at before it gets dropped into our library catalogs.

All of this means it is time to stop teaching people to write as if they’re going to write a lot, all the time, no matter what they do. We need to start teaching two things.

First, the literacy you need in order to prompt an AI to produce its most on-target outputs. You can see this already with the visual AIs that everyone is playing with. The best outputs come from the people who have the literacy and the conceptual understanding to steer the AI towards a high-value outcome.

Second, we need to teach people when their writing needs to their writing. When there is an urgent need for a real human being to be writing their most personally distinctive prose in their most identifiable and expressive manner.

At least some of that effort might not be about teaching writing, it might instead by an attack on the emptiness of some forms of organizational communication that ought to be more human and idiosyncratic. Most business and organizational leaders approach writing as an exercise in limiting their liability, as avoiding saying the wrong thing. Which means their writing says nothing and expresses little actual feeling. We need to figure out where we might want to see more high-value expressive writing or authentic communication and where we’re perfectly fine with informational expression that requires no real sapient mind behind it.

More urgently, we have to start limiting how much writing we do in classrooms. We should not be using it as the primary means for measuring learning other than writing itself. Or we should be deciding how to teach content where distinctive expressive writing about that content is simultaneously desirable, possible and rewarded. To me, that at least means much less writing, with much more effort and attention put into the writing that we actually do. It probably also means figuring out how to prompt expressive writing better than most of us do in our classrooms. I suspect for many faculty, asking for maximally expressive and individualized writing is done by assigning open-ended exercises with few rules or boundaries. Instead, we might be asking students to read on one hand the dullest and most conventional kind of “review essay” that clutters the back end of many scholarly journals and on the other hand to read something like a review essay by Patricia Lockwood and ask them which one they’d rather be credited with writing—and which one they’re confident an AI couldn’t have written. Those are very constrained exercises, in their way, but what makes Lockwood expressive and the average journal review essay dull is not just the quality or invention of the prose but the difference between having something to say and having nothing to say.

So the skill we need to re-invest in is simply (not so simply) this: having something to say. Which I think is precisely what writing in college succeeds in absolutely murdering in most students.

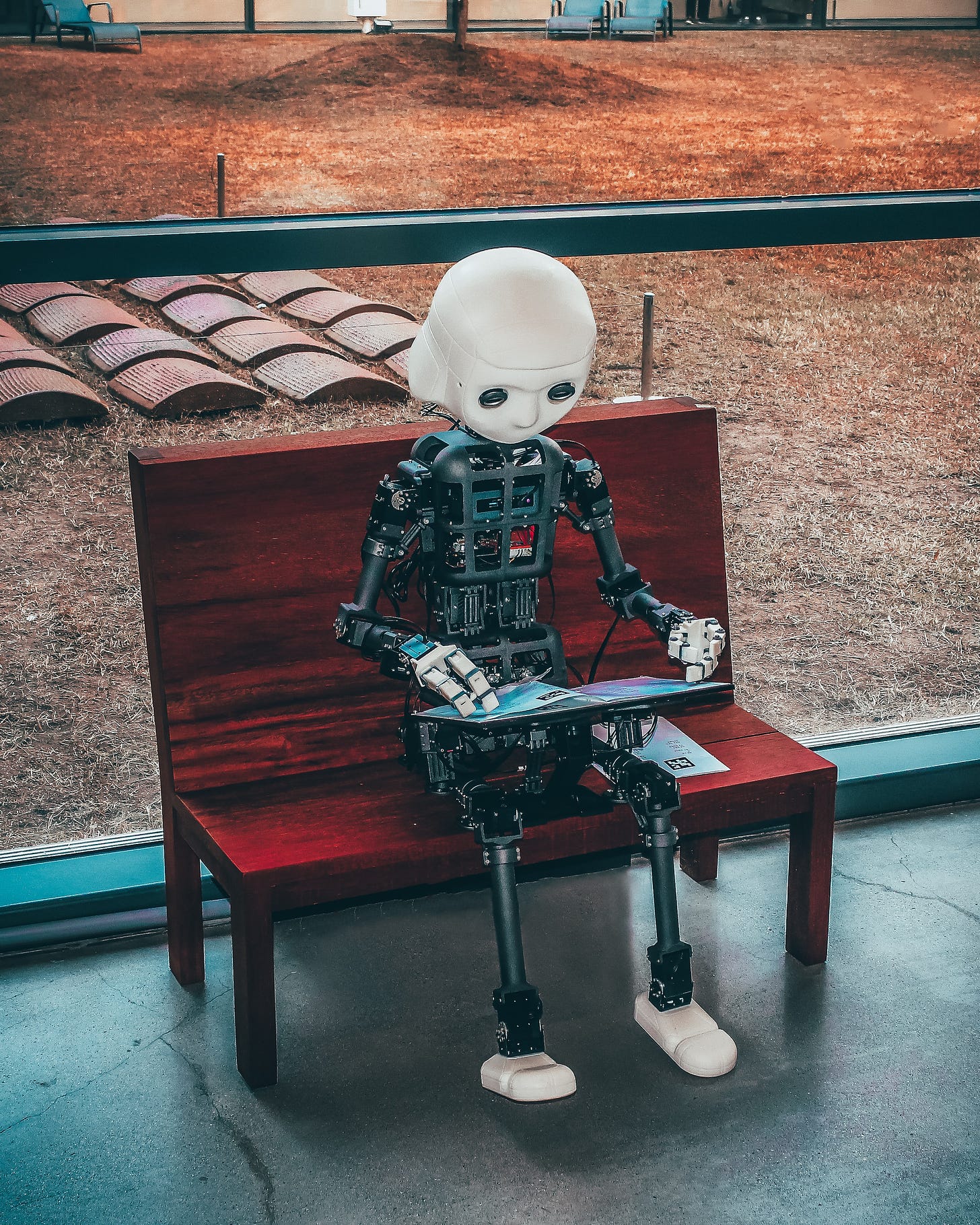

Image credit: Photo by Andrea De Santis on Unsplash

Worthem’s piece is good. I should be relieved that retired me is through with and testing commands. Maybe a college learning setting can be something that doesn’t foreground testing. Perhaps testing could be reserved for the end stages of completing a concentration or through professional credentialing processes. But what I am really thinking about from Worthem is how much of “the oral” we’re not able to grasp or imagine.