Gastrodome: B Is For Basil

B Is Unfortunately Also For Bronchitis

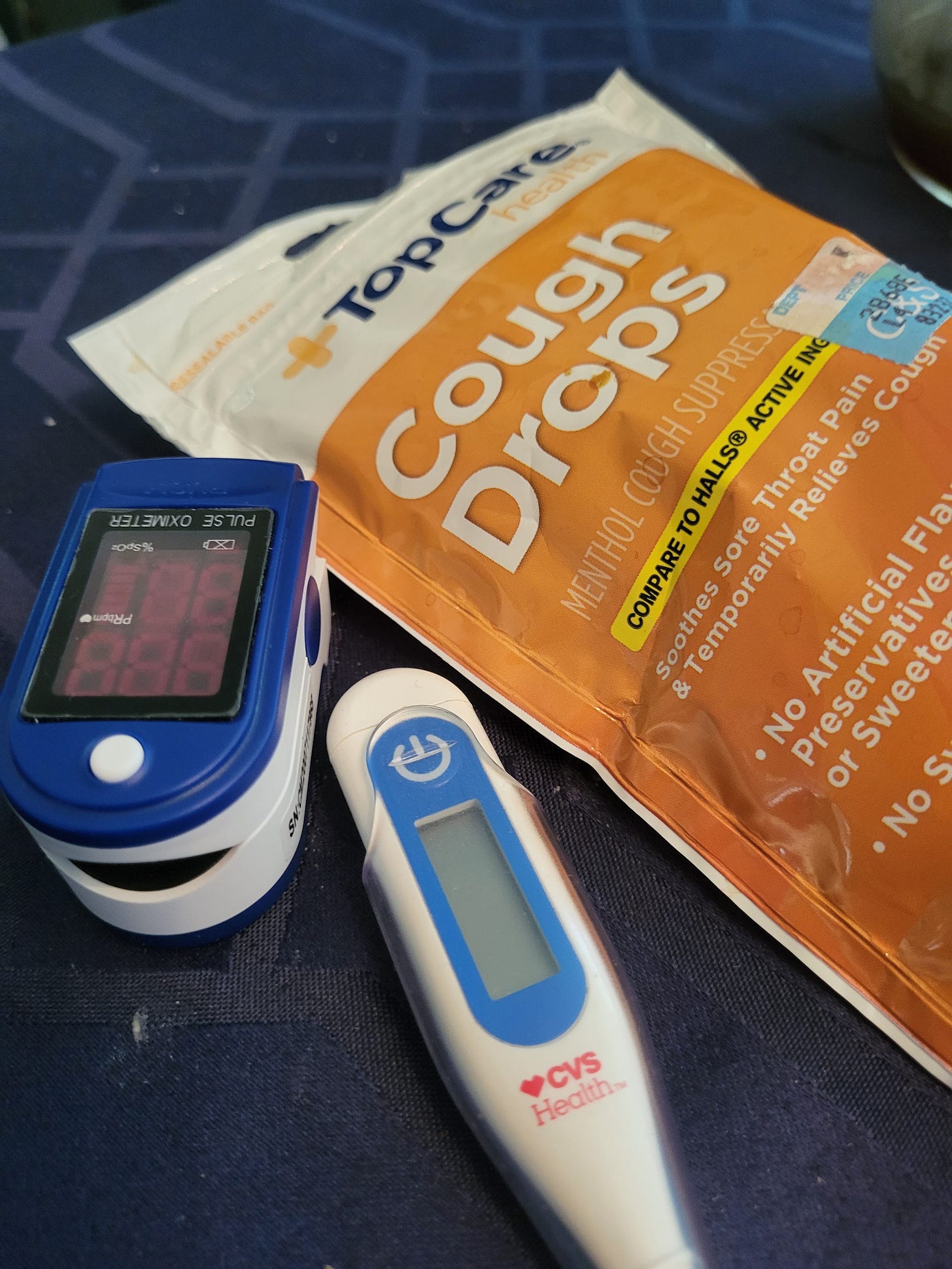

Well, that was a week. Avogolemeno has some healing powers but it couldn’t really stand up to acute bronchitis, which is what my seeming cold last week decided to blossom into. Three boxes of tissues, one prescription of antibiotics, a lot of cough medicine and some sleepless nights later, I can just about handle typing without wheezing and exhaustion.

I might even feel up to venturing outside to my garden and cutting some fresh basil. In a given year, I usually grow oregano, thyme, mint, rosemary and basil. Oregano and thyme are more or less fine as dried herbs. Rosemary isn’t ever an essential, it’s just nice to have. Mint is fairly versatile but I can live without it.

Basil, though, is mandatory, and it has to be fresh.

Dried basil brings nothing to any recipe in my view because it completely lacks the aromatics that make fresh basil so powerful as a presence in any dish. There are ways to extend fresh basil past the summer—the leaves freeze somewhat well, or more commonly, a pesto made with basil can freeze and provide a pretty good blast of fresh basil flavor all the way to July of the following year. Of all the greenhouse produce that Americans can get in their supermarkets off-season, I think I appreciate being able to get basil the most, though hydroponic basil always feels to me as if it isn’t quite the same as fresh basil grown outside in a hot, humid summer climate.

Basil is one of many foods that are perceived by contemporary consumers as deeply historical components of national or ethnicized cuisines. Both Italians and Italian-Americans frequently describe basil as an essential flavor that they presume has been eaten for centuries. As is often the case, the historical reality is something else. Basil wasn’t widely eaten as part of various recipes or dishes in Europe, including Italy, before the late 19th Century. On the other hand, it’s got a deep history of cultivation and use in Old World societies including South and Southeast Asia, the Mediterranean, and West Africa. Before it was a component of sauces or salads, its most famous use was medicinal and aromatic, and its popularity for those uses, either the whole leaves or oil produced from them, shows in part in the range of cultivars found in various regions and agrarian systems around the world.1 It’s also famous for repelling insects, and I’m at least of the opinion that it bugs some mammals too. It’s one of the few things I’ve never had a deer or groundhog take even an experimental nibble of, which is saying something—I’ve got some maniac deer around this year that have even been taking a big chomp out of Carolina Reaper hot peppers.

Most years I’ll grow several variants of sweet basil, in part because I find that they can have a fluky time in the late spring and early summer—if one variety struggles, the other will do ok. Many years I’ll also grow Thai basil and occasionally lemon basil as well. Growing it is important partly because it so quickly loses aroma even as a cut fresh plant. Stick some fresh leaves in the refrigerator and frequently by the next day they’re a withered shadow of what they were the day before.

For the same reason, I prize it most as an uncooked component in various dishes—chopped roughly into pasta or made into a pesto (which will hold the fresh flavor for a fair number of days), added into a salad of fresh tomatoes and lemon juice, put into a sandwich, cut into scrambled eggs at breakfast, chopped over some roast or grilled meat or fish. It’s also pretty great as a garnish in simple summer drinks—lemon juice, basil and gin, for example, or as a infuser ingredient in vodka if you’re into that. It would be one of the few herbal ingredients I’d think of incorporating fresh into an ice cream or infusing into cream for some other dessert.

(The basil here is underneath the pea shoots and the quickly-friend chiffonaded collard greens, but trust me, there’s a lot of it.)

I will drop it in some sauces, but usually only near the end, so that the flavor doesn’t vanish entirely, and I’ll use it in marinades of various kinds. Like I said, I’m happy to have access to it throughout the year, but there is also something about it that really defines the period between mid-July and mid-September for me, to the point that it sometimes feels disorienting to eat it in midwinter.

It’s interesting to think about what happens to a plant or ingredient that becomes redefined as food that has an older history as a consumable linked to its odor and its impact on digestion and health. In the case of basil, I don’t think it loses anything important when it’s in that role as a fresh herbal addition to summer food—the intensity of its smell makes me feel healthy and warm and the simplicity of its use makes everything feel easy in some sense, as much good summer cooking ought to feel. When I’m on the mend, as I am today, that feels like what the doctor ordered.

Spence, Charles. “Sweet Basil: An Increasingly Popular Culinary Herb.” International journal of gastronomy and food science 36 (2024).

Sorry you’ve been sick, Tim! Hope you are fully recovered soon.