The Journal of African History published its first issue in 1960. As it turns out, this is a fairly interesting moment to peer into not just for my field, but in terms of the history of post-1945 global academia. In some ways, 2025 threatens to be an abrupt end of that era in the United States, though the strangling grip of austerity and bureaucratization has done its damage in the United Kingdom and elsewhere.

In 1960, two groups of faculty in the Anglo-American academy were converging on declaring African history to be a legitimate field of scholarly inquiry that should have its own dedicated tenure lines, curricular offerings, graduate training and specialized journals.

The first were British and Commonwealth professors who had returned from being posted as administrators, teachers, and technical experts to British possessions in sub-Saharan Africa, some as early as the 1930s, others in the period from 1945 to 1958, and had developed their generally sympathetic perspective towards African societies and their acceptance of decolonization into a line of expertise as they pursued advanced degrees. This group had coalesced strongly through two conferences held in the United Kingdom in 1953 and 1957, where they mapped out existing lines of research, projected out new lines of promising inquiry, and planned the development of research institutions and training in colonies that were plainly heading for imminent independence, most notably Ghana, Tanzania, Kenya and the territories that were part of the short-lived Central African Federation, which eventually became the nations of Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe. This group was primarily focused on imagining the knowledge that a postimperial Britain that was still the center of a Commonwealth would need to maintain a constructive relationship to its former colonies and on making a benevolent if paternalistic gift to the new nations of Africa by helping them to develop a “usable past” that would help them cultivate national identity while also steering them away from more militant or pan-African visions.

The second were American academics whose doctoral training had generally been focused on studies of the British Empire or occasionally a more comparative perspective on European imperial expansion in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, but who had responded to the rapid development of American governmental interest in the rest of the world during the Eisenhower Administration by shifting their expertise towards the study of sub-Saharan Africa. This was the Cold War creation of “area studies”, underwritten by the U.S. federal government, that aimed to develop expertise in language, culture, and history that would help the United States make sympathetic connections to the new nations of the Third World while also assessing their potential political and economic alignments and policies for opportunity and threat.

Whether the professors in both groups fully apprehended and supported the larger governmental or national ambitions that pushed fields like African history forward, the fact is that the funding that those ambitions made available, along with the rapid expansion of research universities overall as the Baby Boomers poured in, made it all happen, and led to the rapid creation of the characteristic infrastructures that affirmed that a specific field of expertise was “real” within the university. That included professional associations (the African Studies Association in the United States was started in 1957, for example) and journals.

I did a bit of reading last week in preparation for writing this column, in particular the memoirs of several of the founding editors of the Journal of African History. One of them, Philip Curtin, does not discuss the founding of the journal at all, though he has a fair amount to say about the establishment of the field of African history and “area studies” in the late 1950s and early 1960s.1 However, the British historian Roland Oliver does provide some interesting details on the journal’s creation in his memoir In the Realms of Gold. He asserts that it was primarily a consequence of the 1957 conference on African history in the United Kingdom, that he and other attendees felt a very strong need for a journal, and that they began conversations with Cambridge University Press about starting one.

Oliver also gives a really interesting description of what the 1957 attendees came up with as the defining priorities of this new field which the soon-to-be created journal would help to push forward.

African history must from now on be Africa centred. Doctoral students must be steered away from topics concerned mainly with European activities or the policies of the colonial powers. Everything that had been done by colonial historians must be rethought in light of the new criteria. Everything still to be done must be relevant to the African consumer. Documentary research must be directed to local as well as metropolitan archives. Literary evidence, so largely generated by outsiders, must be tested from eyewitnesses or oral tradition. Most new research must be undertaken at least partly in African countries, and historians must, as their numbers grew, pay as much attention to evidence in African languages as anthropologists and sociologists had long been in the habit of doing. (Oliver, In the Realms of Gold, pp. 167-168.

My first thought on reading this passage is that this exposes from the outset a significant divergence between the British and American academy’s approach to institutionalizing African history. Oliver makes clear that the British academy made space for African history first, but also that American study of the field grew quickly after 1960. The divergence, I think, is between a post-imperial vision and a Cold War hegemon’s vision. Oliver’s summary of the 1957 conversation lays out that African history needed to be in and of Africa as quickly as possible, and for the benefit of the “African consumer”. My sense is that many practitioners of the emerging field in the American academy didn’t think that way for a variety of reasons.

That will be at least one of the assumptions that I’m looking to test in this re-reading. Another will be whether any of the scholars who stepped forward to publish in the first decade or so consulted, referenced or drew in prior writing about African history within the African diaspora. Oliver’s memoir describes very active attempts to draw in African intellectuals and to recognize the first generation of Africans who had attended universities in the UK and US, which included a number of men who were part of nationalist parties and movements, and to accelerate the movement of African diasporic and African intellectuals through those institutions in order to recruit more such experts. Eric Williams’ Capitalism and Slavery, published in 1944 (after meeting considerable resistance from academic advisors and then some British leftists) was out there as one work that might have been called upon, and there were a great many published or available historical studies and narratives written by Africans that were not just source material but also scholarly in some respect that late imperial administrators were variously aware of. My sense has always been that the white male academics who were at the center of JAH early on clung very tightly to their sense of having invented or created the field (Oliver and Curtin both call themselves “pioneers” in their memoirs), but I am now wondering whether that sense will emerge out of the actual publications placed in the journal in its first decade.

Reading from the front of the first 1960 issue of the journal is a fascinating exercise even before I get to an article. Only one of the founding advisory board was based in a U.S. institution (Curtin), four were based in institutions in sub-Saharan Africa, and two in Francophone European institutions.

The books advertised on the front pages include two surveys of regional African history, specialized archaeological monographs, works from the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute, and a guide to customary law, as well as works about Britain and its foreign affairs.

That is a guide to the articles as well: there’s archaeology, there are studies of imperial government, there is anthropology that has a historical dimension, and there are methodological analyses aimed at the production of work going forward. (Curtin has a survey of archives available in sub-Saharan Africa, and Jan Vansina an essay that sets out some procedures for doing oral history.) There are a couple of essays I recognize and have read before, including an essay by C.K. Meek that inquires into the source of the name “Niger” for the river and thus also of “Nigeria” as a soon-to-be nation. Some that I haven’t read I know paratextually via their inclusion in later work, such as the essay by Ivor Wilks and Margaret Priestley on the chronology of Asante monarchs.

All of this makes me realize it’s going to be hard to decide which article to look at, but this time I picked something semi-randomly that I didn’t know, which is James Walton, “Patterned Walling in African Folk Building”, pp. 19-30. I’d never heard of Walton, so this felt like an opportunity.

After reading, I felt a great need to know more about his other work and where he was in 1960, which turns out to uncover an interesting aspect of the field at this stage. Walton was a local Yorkshire antiquarian who was interested in material culture, especially rural architecture, essentially as a hobbyist. After World War II, he took an administrative post in Lesotho and then decided to stay in Southern Africa, moving to Cape Town, where he got a job as the managing editor at Longman’s. He resituated his interest in “vernacular architecture” to southern and east Africa and began to publish monographs and journal articles in archaeological, anthropological and historical publications.

One of the things that struck me right away is that this article is valuable simply because it has photographs of material culture sites and I am not entirely sure that all of them are intact today. (This turns out to be an important part of his scholarly legacy generally: a lot of visual documentation of buildings, rock art and material culture.)

Rhetorically, the essay is an interesting and slightly unsettling look into the mixture of experiences and expertise that were inflecting into JAH at the outset. There’s a disarming sincerity and openness about method and knowledge production. Walton starts off by talking about how he happened to be spending some time near Lake Nyasa in what is now Nkhotakota, Malawi, and an elderly local schoolteacher showed him the doors on the mosque while talking about the late years of the precolonial caravan trade with Zanzibar, which prominently included slave-trading. (The schoolteacher professes to have been involved with the last years of the trade.) The mosque, as Walton sees it, shows strong connections in technique and aesthetics to coastal Swahili styles of building.

From there, Walton notes that the patterns in that architecture also seem to resemble some of the walled sites found in eastern Southern Africa, most prominently at Great Zimbabwe. At this point, I pretty well knew what was coming next, and I was right: Walton references what was still viewed as a legitimately scholarly controversy at the time, which is whether those sites, most particularly Great Zimbabwe, were built by Arabs or “Semitic” outsiders—the same idea that produced H. Rider Haggard’s colonial novel King Solomon’s Mines. The intellectual history here is tangled, and remarkably persistent in the sense that I will still run across people online who have it lodged in their heads that Great Zimbabwe was built and inhabited by people other than the Shona-speaking societies in that region. The scholarship has long since discarded that idea and accurately attributed it to racist ideology by white settlers and colonial officials who simply couldn’t credit Africans with complex stonework architecture.

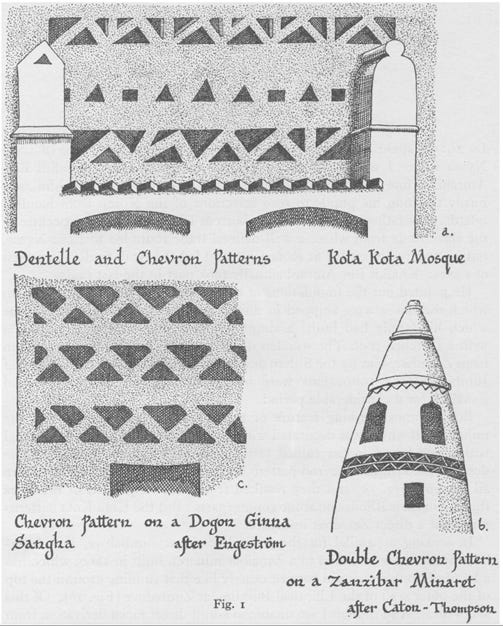

Thankfully, Walton seemingly wasn’t a dedicated proponent of that theory. What really struck me is the casual, matter-of-fact way that he treats his initial source as having valuable expert insight into the mosque’s architecture considering that elsewhere in this first issue of the journal, other historians are already squaring off about whether oral history can ever be a useful evidentiary source and what elaborate methodological procedures might make it so. But I’m also struck at the (somewhat mind-numbing) attention to structural details—much of the essay is exactly what the title says, an examination of patterning (use of alternating colors of stone, construction of decorative elements in walls, and so on).

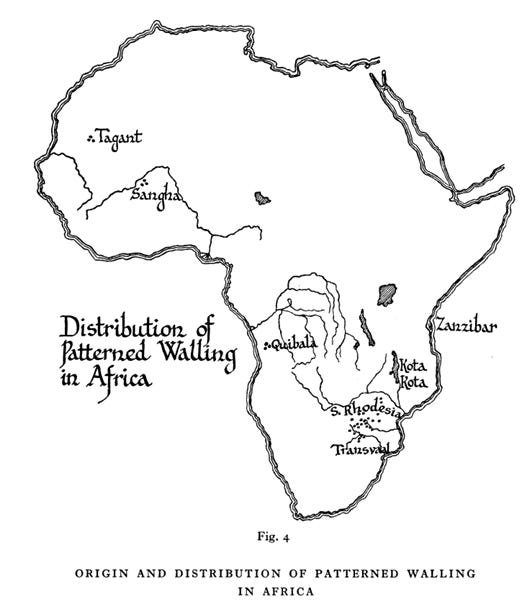

The more startling revelation of the mindset at the time is when Walton leaps from sites that are plausibly connected through a diffusion of architectural techniques and aesthetic preferences through trade networks and population movements to Francophone West Africa.

That’s a point where you realize suddenly that the subject of “African history” for some of these early scholars was an implicitly racial subject—that for some of them, the way to move away from a focus on the construction of imperial administrations and economies was to look for histories made visible in archaeology and cultural practice on a continental scale, with the presumption of some deep pattern of diffusion from a single point of origin. I’m far from the first scholar of African history to point out that this idea not only inflected into some ethnohistorical work at this early stage but eventually found its way into Afrocentric thought, primarily though the scholarship of the Senegalese scholar Cheikh Anta Diop. Here the idea is that patterned walling was originally practiced by Berber peoples in North Africa and diffused from there all the way to south-eastern Africa. The last few pages of the essay are disorienting for me in this respect because I realize that the conversation that Walton was swimming in really didn’t have any kind of detailed model of the movements of linguistic-cultural formations within sub-Saharan Africa, no really worked out understanding of the possible or likely chronologies of interactions and influences, and no opening to the thought that different African societies at different moments of history might have simply come up with material practices that have a sort of resemblance to one another. It is more or less the same method that many intellectuals used in the 19th and 20th Centuries to assert that there must be histories of dissemination from a single original point because objects and buildings and art have resemblances.

While it’s important to not reject those inferences out of hand—there do turn out to be connections and interactions over long distances and time periods that run counter to our understandings of distinctiveness and divergence—I can nevertheless see in reading this essay the absence even of the thought that a direct lineal connection between Berber architecture in antiquity and Great Zimbabwe seems both improbable on the face of it and also entirely undemonstrated by any sort of concrete evidence. This is often what happens when we read past scholarship in history, no matter what the field—you see both the origins of some ongoing debates and valid knowledge and the degree to which some kinds of assumptions and common sense not only weren’t questioned at that moment but likely couldn’t have been questioned from inside certain kinds of formations of received wisdom and social status.

This is very likely not the last time I will be writing about Curtin’s career and contributions to the field in this series of columns. Some of my readers doubtless know that I was for a brief time a student of Curtin’s. It was an unhappy experience, and I still do not look on him kindly as a teacher. His memoir is an odd work, at any rate, and often does not help place him in relationship to his field of study, perhaps in part because of what he himself describes as an ambivalent attitude towards area studies and narrow specialization. It’s not just that, however. Jan-Bart Gewald’s review of the memoir in Africa Today sums it up rather well: “I should have preferred more reflection on the development of African studies than on detailed exposes of divorces, kayaking, ice-climbing, and Shay locomotives in the woods of West Virginia.”

So interesting to me. I am very tempted by the Meek piece, myself, which I don’t think I’ve read before. But I’ve put that literature behind me now. Thanks for diverting me from doom scrolling for a little while, Tim.

So canny a perspective of a “moment” in the production of history. An aside on your commentary on the Walton piece. It reads like a reader’s critique which might have sent journal editors reading back to author a call for revision. And this led me to a second aside: has anyone worked on the archive of the editorial work on the JAH? There must be some sources there that magnify the crack-up on the Oliver-Curtin relationship, for one thing and on the fate of this strange idea of the “”African consumer.” PS and, Tim, you were working on this as we lost BA Ogot at age 95, an historian who had a deeper view of the emergence of the field than either Oliver or Curtin, at least in length of time in the field.