So far, the most interesting part of this little experiment for me personally has been two-fold. First, seeing scholars who I have read for their fully assembled canonical studies in the process of assembling that scholarship, and second, to see some really disparate genealogies of British, French and American writing about the African past assembling towards a self-conscious sense of being a “real field” within the discipline of history.

At times, that involved some really mind-numbing score-keeping. There’s a review essay by John Fage, one of the journal’s co-founders, in the second issue of 1961 (there were only two) that assesses a new continent-wide anthropological synthesis of knowledge about African societies written by George Peter Murdock, who was a professor at Yale. I haven’t read Murdock, and don’t really feel any inclination to after struggling through Fage’s painstaking attempt to correct him on various details while also trying to be encouraging towards the project of knowledge production about Africa. (Though Murdock’s type of work was very important to mid-20th Century American anthropology and was part of an older kind of ethnological knowledge that the early Cold War project of area studies often drew upon.) The Fage essay is not at all fun to read but it is rather like peering into a kind of stream-of-consciousness attempt to wrestle Western knowledge about Africa out of a colonial framework and into something more empirical and constructive, to make African history seem “normal” within the wider discipline.

In the end, I picked an essay by Michael Garfield Smith entitled “Field Histories Among the Hausa”.1 (So far, I’m pointedly staying away from essays that are closest to my own specialized knowledge in order to intensify my sense of discovery in these readings.)

Smith was a Jamaican anthropologist who worked in West Africa and in the Caribbean. Somewhere back in the mists of time in my own career I read a book he wrote with Leo Kuper called Pluralism in Africa, but I didn’t know much else about him. After reading, I looked him up and found myself quite charmed by his career, which included work as an accomplished poet, advisor to the government of Jamaica and late in his career an appointment to Yale University. (I also found out that Andrew Apter, whose work I know well, was Smith’s final graduate student.)

This piece developed out of fieldwork Smith did in West Africa at the start of his scholarly career and it plainly was of interest to the new journal editors for its attempt to sketch out methodologies for doing historical research in Africa that might include ethnographic fieldwork and the collection of oral histories while also drawing on archival documents.

My own graduate training, once I found my cohort and my main advisor, so thoroughly erased methodological and historiographical boundaries between anthropology and history that I struggled to understand what was going on when I happened across some older feud between the disciplines—or even sometimes the elaborate efforts of scholars like Jan Vansina or David Henige to systematize and legitimate a constrained approach to African oral history in order to make using them acceptable to historians generally. (My predecessor at Swarthmore was known partially for his strong hostility to oral history and folklore as a basis for historical research, so even though it’s strange to me, I understand that some of these early Africanists felt they had to undertake this work.)

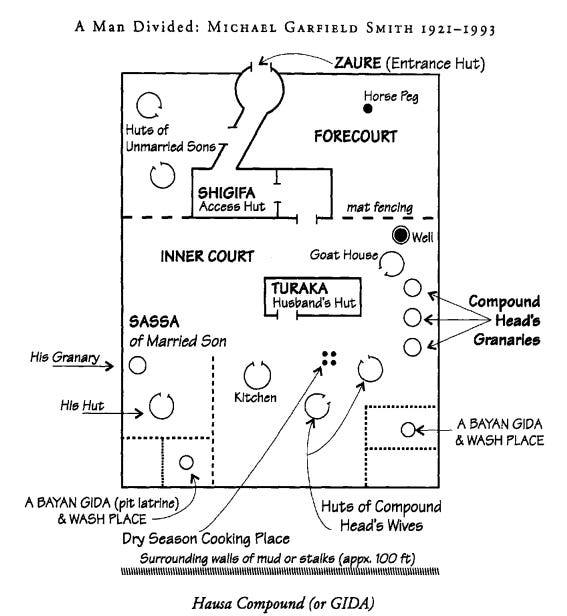

For this reason, I was really quite charmed by Smith’s article, which dispenses entirely with the presumption of some complicated epistemological barrier between anthropology and history as forms of inquiry. He starts with a clear, quick summary of the history of Zaria, presently a part of Kaduna in northern Nigeria, back to when it was an independent Muslim state in the 18th Century whose citizens spoke Hausa or Fulani. It was conquered by Usman dan Fodio and incorporated into the Sokoto Caliphate, a large regional empire that flourished in the first half of the 19th Century and was then subjugated by the British Empire in the early 20th Century.

Smith intended to study contemporary political systems and social structures in Zaria in 1949-50, along with similar work in nearby regions. In a disarmingly matter-of-fact way, he states that the local British imperial officials offered interpretations of what he was observing that differed significantly from his own. “To decide between two opposing views of current Zaria, a historical inquiry was necessary, since current observations were not an adequate test.”2 I just sort of smiled on reading that, because it was so beautifully simple—do some history and see if that doesn’t sort out which group of outside observers understand things the best. It gets a bit more complicated in the next paragraph in that Smith lays out his established interest in retheorizing social structure within sociology and anthropology and explains that historical interpretation might be the lever to accomplish this purpose.

The description of method that follows pretty well sums up how the Anglo-American academy was trying to systematize studying recent African history. Learn the language, particularly “thought-idioms”. Read as much of the administrative record as the colonial state’s local representatives would permit, which at this point was “almost all of it”. Look at maps. Look at king-lists, one of the products of British and French colonial authority, a central ethos of “indirect rule” as a system. Smith exhibits no awareness of the constructedness of those lists, of the ways in which they were an instrument of imperial power—that kind of critique was still years away.

At the same time, he immediately hits a hard methodological wall that was already a preoccupation for the scholars eager to legitimize African history to their skeptical white colleagues: he couldn’t say very much about political authority or social structure in Zaria before dan Fodio’s conquest, before the Sokoto Caliphate, before 1800, so he just brackets that off as unknowable.3 The effect of that decision confines him into the space of British imperial codification of the customary or traditional as the century or so immediately preceding European conquest. His argument with local administrators, it turns out, is not about the epistemological and instrumental priors of their knowledge-making, nor about the effects that conversations with local Hausa elites and authorities have had on his own understanding.

In fact, despite the lack of theoretical fireworks at the outset, he more or less ends up where scholars like Vansina did at this early stage, that he only wants to talk to Hausa “savants” sent to him by British officials so that he can systematize and correct a narrow range of information like the king-lists. Older men, men with verifiable political expertise, men who had been involved in the central administration of the late Sokoto Caliphate or in the transitional period of early British rule, were the premium authorities who he could rely upon. The gold standard, as it was for other historians in this moment, were “specialist historians”, Hausa men who had some formal expertise in the history of Zaria.

There’s something so important going on here—it feels right at the edge of breaking out of the limitations of a Western researcher sitting behind a desk, imitating a British official and demanding that people confirm or correct the systematic knowledge he was producing. Reading a biography of Smith,4 he comes off as one of the generation of young Commonwealth university graduates sent to be a helpful partner to Africans in what has been called a moment of “Fabian imperialism”, a reform towards “developmentalism”. What Smith presents in the essay as a systematic enterprise his biographer suggests was perhaps more like a collaboration between himself and an “intelligent and informative local student”. His biographer also notes that Smith’s wife Mary carried out interviews with women, who would have found it improper to speak to Smith himself.5 But Smith doesn’t really get to that point of breaking out even though the totality of the knowledge he presents about the history of Sokoto in this article eventually goes well beyond the limitations of the history that colonial administrators had sought to collect.

Smith’s devotion to structural accounts is part of why he doesn’t break out of that mode. Not only is he trying to reassure scholarly readers of the systematic character of his evidence, of the rigor of his methods, but he is eager to render Sokoto’s history as a state in terms of its formal character—essentially a structural account of a structured thing. What I can’t help but ‘hear’ around the edges of his inquiry, because I’m at the other end of decades of historical writing, is all the information that he was told but bracketed off—essentially accounts of the meaning of Sokoto, of the debates and ambiguities that attended on its power. That bracketing is summarized at the end as simply as the methodological commitments undertaken in the beginning: “Data yielded by systematic inquiries differ clearly from popular traditions and narrative”.

That sums up a lifetime of difference one lineage of historical-anthropological study and the rest of the social sciences, between work that seeks its legitimacy in reporting out the messy and tumultuous ways that societies know (and do not know) themselves and the feeling that knowledge production has to be protected from that noise. Right at that moment, I felt I was witnessing a tension that blossomed in the field later on between scholars who were working hard to produce an account of African history that could be used in comparative analysis and that saw itself as dignifying the new nations of Africa by presenting the African past in rational, universal, structured terms and scholars who were drawn to the substance and meanings of what people actually said and did both now and in history without presuming that this would eventually be pared down into a set of well-structured priors.

Much as I liked Smith on the page in reading this article and saw enduring value in the work he did, there’s a little part of me that mourned the “popular traditions and narrative” that I feel sure he was also told about during this work. I don’t know enough about Smith’s total output to know whether all of that went somewhere else—Douglas Hall’s biography certainly seems to be drawing on some of that information in describing the work he did in Nigeria. But it feels to me like real progress that the discipline of history (and anthropology seeking to create historical knowledge) eventually broke down the severity of the legitimating strategy that Smith felt so strongly committed to in this essay.

Smith, M. G. “Field Histories among the Hausa.” The Journal of African History 2, no. 1 (1961): 87–101. http://www.jstor.org/stable/179585.

Smith, “Field Histories”, p. 88.

I don’t know if I’m going to get the chance in this series of essays to fully break out a point that occurs to me here. It’s a dangerous thought because it tempts me to a new research project, which I know from long experience is a temptation that has a strong pull on me when I’m feeling too disconsoled about the old research projects that I haven’t finished. But the thing that’s on my mind here is something that has tugged at me a lot in my teaching for the last decade, which is that in the 19th Century, Europeans spent a tremendous amount of effort working to forget what they already knew about Atlantic African societies and their history, to actively create an Africa that was without history. I don’t think we often pay attention to that process—I almost feel rather peculiarly as if Mungo Park’s sympathetically detailed account of his travels accidentally inaugurated the project of forgetting. If a later JAH article gives me a chance, maybe I’ll follow this tangent further.

Douglas Hall, A Man Divided : Michael Garfield Smith: Jamaican Poet and Anthropologist, 1921-1993. Kingston, Jamaica: University of the West Indies Press, 1997.

Hall, A Man Divided, pp. 30-31.

Thanks for this Tim. It is kind of a privilege to see a scholar early on in their research struggling to organize a position in a field, or in fields, that were changing or needing change. Smith might seem like he's not recognizing all the possibilities but I'm guessing his attempt to navigate fixed positions was not esay. I didn't know of Douglas Hall's study and that's really interesting. On your first two critical readings of early JAH, it is a wonder it survived to present some incredibly important work. As I mentioned before, it would be really intriguing to review the editorial correspondence around the selection of these early pieces for the journal.

Yes, thanks for sharing this, Tim. I was quite fascinated by it and started to wonder if there were connections between this Smith and Raymond Smith, who was on my dissertation committee. (Not kinship connections but anthropological ones, which is maybe kinship by other means.) I’m enjoying this new series of yours,